“It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.” – W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk

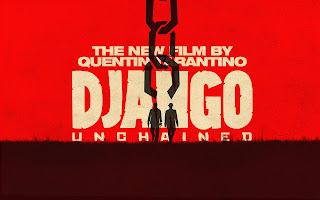

When I

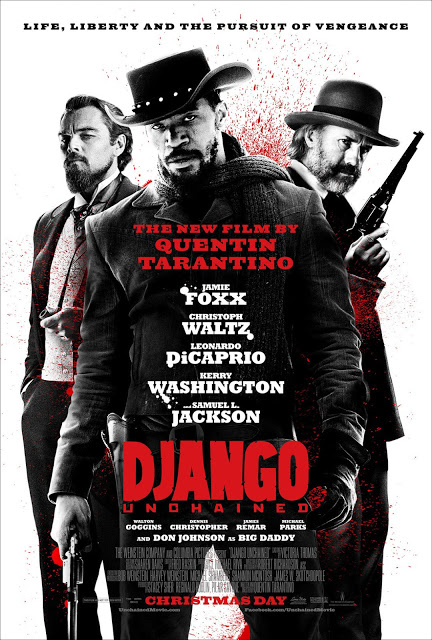

first wrote about Django Unchained, I focused on the power of Django’s story, and how Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz) and Quentin Tarantino give Django the “white access” he needs to get into Candyland and into movie theaters.

I was excited and hopeful about what the film could symbolize on a grand scale, that a revenge-fantasy that shows the horrors of slavery and has a Black protagonist who overtakes his oppressors was a box office hit and was set to receive numerous award nominations.

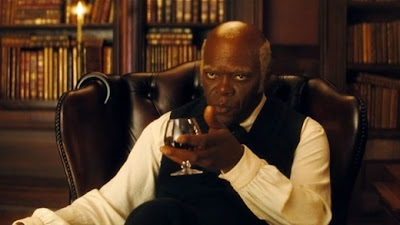

My excitement was short-lived. Jamie Foxx (Django) and Samuel L. Jackson (Stephen) were shut out of acting categories for both the Golden Globes and Academy Awards.

While their co-stars are completely deserving of recognition for incredible acting (Waltz and Leonardo DiCaprio were nominated for Golden Globes and Waltz for an Academy Award–Waltz won both), Foxx’s lack of nominations is symptomatic of a larger Hollywood problem–not only whose stories audiences see, but also whose stories get awards.

When Tarantino understandably felt uncomfortable with the thought of filming scenes of a slave auction and brutality against slaves, he struggled with not wanting to film those scenes in the American south. He sought advice from Sidney Poitier (the first African American to win a Best Actor Oscar). His response:

“‘Sidney basically told me to man up,’ Tarantino says. ‘He said, ‘Quentin, for whatever reason, you’ve been inspired to make this film. You can’t be afraid of your own movie. You must treat them like actors, not property. If you do that, you’ll be fine.'”

Overall, Tarantino was fine. His Black actors, however, were not recognized for their performances (this was reminiscent of his 1997 film Jackie Brown, which received Golden Globe nods for Samuel L. Jackson and the title character, Pam Grier, but only received an acting Academy Award nomination for white co-star Robert Forster).

In an Oscar year that feature films that deal with race (The New York Times recently published an excellent article examining race and the roles of Black men in this year’s Oscar contenders), the acting awards nominations are startlingly white (Denzel Washington and Quvenzhané Wallis being the exceptions).

I want to focus mostly on the Black actors and actresses who have

won Academy Awards, the plots of the films they were in (synopses from

imdb.com) and their character descriptions. I know that this topic is complex and demands analysis far beyond this, but a brief reflection shows a pattern.

[Warning: spoilers ahead!]

Lilies of the Field (1963, Sidney Poitier, Best Actor): An unemployed construction worker (Homer Smith) heading out west stops at a remote farm in the desert to get water when his car overheats. The farm is being worked by a group of East European Catholic nuns, headed by the strict mother superior (Mother Maria), who believes that Homer has been sent by God to build a much needed church in the desert.

– Homer Smith: handyman who provides unpaid labor to a group of nuns

Training Day (2001, Denzel Washington, Best Actor): On his first day on the job as a narcotics officer, a rookie cop works with a rogue detective who isn’t what he appears.

– Alonzo Harris: crooked narcotics officer, killed at the end

Monster’s Ball (2001, Halle Berry, Best Actress): After a family tragedy, a racist prison guard reexamines his attitudes while falling in love with the African-American wife of the last prisoner he executed.

– Leticia Musgrove: struggling single mother, incarcerated husband, object of lust for racist cop

Ray (2004, Jamie Foxx, Best Actor): The life and career of the legendary popular music pianist, Ray Charles.

– Ray Charles: blind man overcomes odds, becomes music legend

The Last King of Scotland (2006, Forest Whitaker, Best Actor): Based on the events of the brutal Ugandan dictator Idi Amin’s regime as seen by his personal physician during the 1970s.

– Idi Amin: Ugandan president, evil, hundreds of thousands died under his regime

Flight (2012, Denzel Washington, Best Actor – pending): An airline pilot saves a flight from crashing, but an investigation into the malfunctions reveals something troubling.

– William “Whip” Whitaker: alcoholic, drug-addict pilot, ends up incarcerated

Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012, Quvenzhané Wallis, Best Actress – pending): Faced with both her hot-tempered father’s fading health and melting ice-caps that flood her ramshackle bayou community and unleash ancient aurochs, six-year-old Hushpuppy must learn the ways of courage and love.

– Hushpuppy: precocious five-year-old girl living in poverty with a dying, abusive father

An Officer and a Gentleman (1982, Louis Gossett, Jr., Best Supporting Actor): A young man must complete his work at a Navy Flight school to become an aviator, with the help of a tough gunnery sergeant and his new girlfriend.

– Gunnery Sergeant Emil Foley: rigid drill instructor, trains protagonist

Gone With the Wind (1939, Hattie McDaniel, Best Supporting Actress): American classic in which a manipulative woman and a roguish man carry on a turbulent love affair in the American south during the Civil War and Reconstruction.

– Mammy: “outspoken handmaid”

Glory (1989, Denzel Washington, Best Supporting Actor): Robert Gould Shaw leads the US Civil War’s first all-Black volunteer company, fighting prejudices of both his own Union army and the Confederates.

– Pvt. Trip: escaped slave, dies fighting

Ghost (1990, Whoopi Goldberg, Best Supporting Actress): After being killed during a botched mugging, a man’s love for his partner enables him to remain on earth as a ghost.

– Oda Mae Brown: con artist/psychic, “confidence trickster”

Jerry Maguire (1996, Cuba Gooding, Jr., Best Supporting Actor): When a sports agent has a moral epiphany and is fired for expressing it, he decides to put his new philosophy to the test as an independent with the only athlete who stays with him.

– Rod Tidwell: football player

Million Dollar Baby (2004, Morgan Freeman, Best Supporting Actor): A determined woman works with a hardened boxing trainer to become a professional.

– Eddie “Scrap-Iron” Dupris: narrator, retired boxer, employee at gym

Dreamgirls (2006, Jennifer Hudson, Best Supporting Actress): Based on the Broadway musical, a trio of Black female soul singers cross over to the pop charts in the early 1960s.

– Effie White: lead singer of the Dreamettes until she gets forced out of the group, becomes an “impoverished welfare mother”

Precious (2009, Mo’Nique, Best Supporting Actress): In New York City’s Harlem circa 1987, an overweight, abused, illiterate teen who is pregnant with her second child is invited to enroll in an alternative school in hopes that her life can head in a new direction.

– Mary Lee Johnston: unemployed, abusive (sexually, physically and emotionally), scams government for more welfare

The Help (2011, Octavia Spencer, Best Supporting Actress): An aspiring author during the civil rights movement of the 1960s decides to write a book detailing the African-American maids’ point of view on the white families for which they work, and the hardships they go through on a daily basis.

– Minny Jackson: outspoken, difficult maid; good cook

Of the four Black men who have won Best Actor Oscars, two are in powerful positions of authority and are evil (they serve as foils to their noble white co-stars), one provides free labor (let that sink in), and the other is a musician. The Black Best Supporting Actor winners quite literally support white protagonists.

The Black female actresses’ winning roles are even more troubling. None of them really has independent agency, except for maybe Hushpuppy–who is a child (she’s also not expected to win). Otherwise the list is full of maids, single mothers on welfare, and one trickster con artist. It felt horrible to even type that.

These characters are comfortable and safe to white audiences. If the character seems

unsafe to white audiences, he or she is punished. Last year, the

LA Times released a

study that Oscar voters were 94 percent white and 77 percent male. Certainly this affects the Academy’s choices.

Now let’s look at the plot synopsis for Django Unchained.

Django Unchained: With the help of a German bounty hunter, a freed slave sets out to rescue his wife from a brutal Mississippi plantation owner.

– Django Freeman: trained, violent bounty hunter, whips and kills white people, burns down a plantation

One of these things is not like the others.

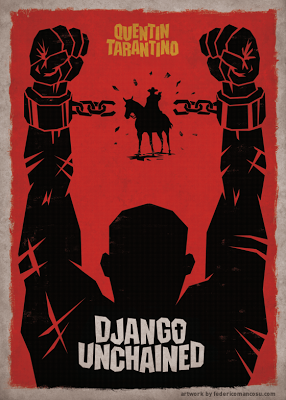

Django Unchained ends with a triumphant Black couple who have gained their revenge, freedom, and love. Think about how vastly different that ending is than those that are provided to Black characters in the films above. Many white couples and individuals end those films successfully, with complex story arcs that show their agency and growth.

When W.E.B. Du Bois discusses the “double consciousness” of seeing oneself “through the eyes of others,” he could very well be talking about modern-day Hollywood. He saw the world looking at African Americans with “amused contempt and pity,” and it’s hard to look at that list of Academy Award winners and not come to that same conclusion.

Meanwhile,

Lincoln has been nominated in three out of the four major acting categories (all white actors). This is a film about abolishing slavery from a totally white and

white-washed perspective (the

omission of Frederick Douglass is unbelievable).

Whose stories get told? Whose stories get accolades?

It’s

pretty clear. The Academy (

94 percent white and 77 percent male) values stories that reflect their privileged consciousness and reinforce the Black double-consciousness that Du Bois was attempting to push through over 100 years ago.

Those chains, it seems, remain unbroken.

—–

Leigh Kolb is a composition, literature, and journalism instructor at a community college in rural Missouri.