|

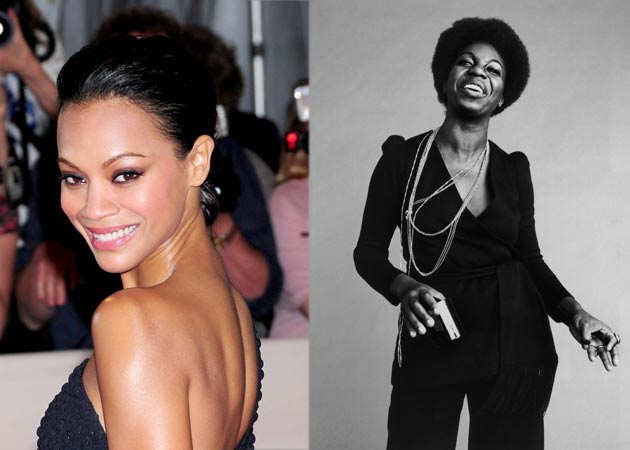

| (L-R): Zoe Saldana and Nina Simone; image via Black Street |

When Zoe Saldana was recently cast as legendary singer Nina Simone in her upcoming biopic, the decision ignited a firestorm of controversy. People have vehemently criticized the decision. Not because Saldana isn’t a skilled actor (she is). But because her skin is much lighter than the music icon.

“I can guarantee that the sense of insecurity and the questioning of one’s beauty that results from a grownup telling you that as a child you’re too black and your nose is too wide, remained with her [her mother Nina Simone] for the rest of her life.”

At The Huffington Post, Nicole Moore writes about Nina Simone and the “erasure of black women in film”:

“Because Simone’s blackness extended as much to her musical prowess as to her physicality and image, it’s perplexing that the film’s production team, led by Jimmy Iovine, expects anyone, particularly in the black community, to (re)imagine Nina Simone as fair-skinned, thin-lipped and narrow-nosed? I guess if you look at Hollywood’s history of casting black female roles, especially in biopics, it’s not all that surprising.”

Hollywood has a massive race and gender problem. Black women’s bodies belong to a dichotomy suffering from either fetishization or erasure. When Black women appear in media, which doesn’t happen nearly enough, they suffer from stereotypes of mammies, jezebels and sapphires. And too many producers and directors clearly don’t understand the nuances of race, thinking any person of color will suffice.

“In the past few years Hollywood has consistently gotten it wrong when it comes to telling black women’s narratives. From the questionable choice of casting Thandie Newton as an Igbo woman in the film adaptation of the novel Half of a Yellow Sun and Jennifer Hudson as Winnie Mandela, to Jacqueline Fleming, a biracial woman, playing Harriet Tubman, when other people are in charge of portraying us, it seems like any brown face will do.”

The Atlantic’s Ta-Nehisi Coates also finds the “bleaching of Nina Simone” problematic and reinforcing systemic racism:

“But this casting (with no shot taken at Saldana) manages to both erase the specific kind of racism Simone contended with and at the same time empower it.”

Most white people probably don’t realize the painful history of colorism and skin shade hierarchy — dark vs. light skin — Black women continually face. When the media portrays Black women, we often see women with lighter skin and more Caucasian features. Both L’Oreal and Elle photoshopped Black women — Beyonce and Gabby Sidibe — to make their skin appear much lighter. In film, advertisements and magazine spreads, the media often whitewashes black women, continually perpetuating the unachievable attainment of the white ideal of beauty.

“Skin color and its importance around the world—and particularly in the African-American community—has been a hot-button issue for generations. The debate over skin color and its painful origins dates back to the days of slavery, when lighter skin often equaled a better overall quality of life. With more pronounced European features, bearers of a lighter complexion were also considered more attractive than their darker-skinned peers. Possessing this trait was believed to open the cracked doors of opportunity ever wider.”

Due to white privilege, white people don’t agonize over their skin color. We don’t have to worry if someone will harass us or follow us around in a department store, thinking we’re going to steal merchandise simply because of our skin. If we move, we don’t have to worry about finding neighbors who don’t like us because of our skin color. We don’t have to fret over something as simple as putting on a Band-Aid which won’t match our skin tone.

“The hard truth is this: if we spent more time creating media instead of criticizing it, there’d be way more diversity in representation, and way more stories and perspectives to which white people can be more frequently held accountable.

“Pushing for ownership of both the infrastructure and content that portrays our lived experiences – that is the crux of the issue; not just the politics of light vs. dark-skinned actresses. So, whereas I am completely on board with calling out the colorism behind the biopic’s casting choices (and the harmful message that’s being sent to young, dark-skinned black girls everywhere by having a light-skinned woman play Nina Simone) there aren’t enough strong lead roles written for women of color in Hollywood for me to fairly tell Zoe Saldana, a hard-working, talented brown woman to ”sit this one out.”

Here at Bitch Flicks, we talk a lot about the need for more female filmmakers and women-centric films. One of the takeaways from the Zoe Saldana/Nina Simone controversy is that we desperately need more women of color filmmakers.

“So black women, one of the most sought after audience demographics for movie studios, aren’t behind the camera providing insight into our culture. This leads to a misrepresentation of the black community on the silver screen. Often, we are caricatures of ourselves, as evidenced in Jumping the Broom and other projects, which leads to resentment for what the media machine represents in our communities.”

When a young Black female tennis player is told she’s too fat to receive funding, when the Swedish Minister of Culture and rapper 2Chainz eat racist cakes of dismembered Black women’s bodies, when the media cares more about criticizing Olympic gold-medal winning gymnast Gabby Douglas’ hair than her performance — we as a society clearly have a fucked-up, racist and misogynistic problem denigrating and oppressing Black women.