White, straight boys in suburbia: I’m a white person who grew up in the suburbs and I’m sick of seeing you in films. I watched Me and Earl and The Dying Girl (with its one cliché-ridden Black character) and if I’d been at home instead of at a theater I would have spent nearly the entire runtime saying aloud, “I don’t care. I don’t care. I don’t care.” I couldn’t stand the privileged behavior most straight, white, cis, able-bodied boys exhibited when I was in high school–and most other high school girls, even the straight ones, along with guys who weren’t straight–couldn’t stand it either. Together we formed a majority. My high school was so ordinary, I feel secure in extrapolating that most high schools are the same–but films about high school focus on the same people most of us tried to avoid.

Television is a better place to see different types of high school kids. On The Fosters 14-year-old white best friends Jude and Connor have become an uncloseted couple, with support from Jude’s queer foster parents, (Lena, a Black school principal and Stef, a white cop) and resistance from Connor’s single, straight Dad. A couple of weeks ago Jude and Connor went to a queer prom, devised by teenager Cole (the platonic date of Jude’s older sister, Callie, for the event) a white trans character played by a young trans guy, Tom Phelan: we see his top surgery scars when he takes off his shirt to swim at a beach. The show, which in many other ways is just as soapy and contrived as other TV dramas, in these details reflects the world outside TV many of us recognize, which no one, if they had most “high school” movies as the only evidence, would guess existed.

We can see a portrait of high school life for kids who aren’t white, straight and suburban in Dope, the film written and directed by Rick Famuyiwa (whose parents are Nigerian immigrants) which focuses on a main character, Malcolm (Shameik Moore) who is a half-Nigerian, straight, high school senior, living with a single US-born mother (Kimberly Elise) in a “bad” Los Angeles neighborhood. He also happens to be a nerd who gets good grades, is obsessed with early 1990s hip-hop, clothing and hairstyles (he has a flattop fade) and has two friends in school who share his interests: Jib (Tony Revolori) and soft butch, Diggy (Kiersey Clemons). As the film tells us, some of the stereotypically “white” things the three like include Black alternative band TV on the Radio and Black actor and comedian Donald Glover.

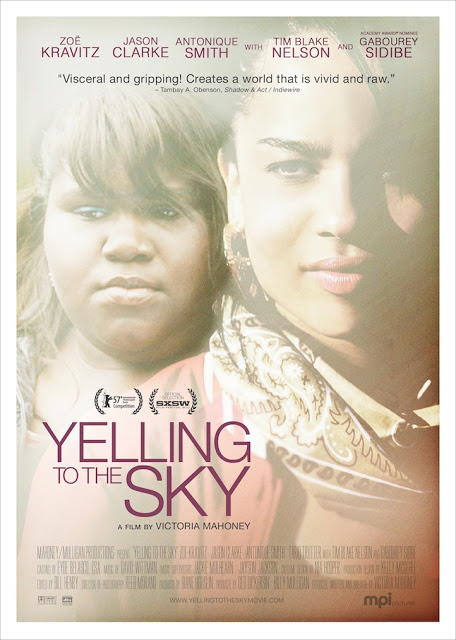

Listening to Malcolm describe his neighborhood, where he and his friends have to avoid certain streets or the BMX bikes they use to get around will be stolen, or his high school, where we see his new sneakers taken off his feet by bullies is a refreshing change from the main character in Earl (and the many movies like it) endlessly droning on about the cliques in his boring, mostly white, suburban high school. But living in his neighborhood means Malcolm has contact with people many suburban, white teens don’t, like drug dealer Dom (A$ap Rocky) who takes a liking to Malcolm saying of him, “He’s probably got one of those photogenic brains.” Dom uses Malcolm as a go-between to the beautiful Nakia (Zoë Kravitz looking stunningly like her mother, Lisa Bonet, did in the late ’80s and early ’90s) who is studying for her GED. Nakia tells Malcolm she’ll go to Dom’s birthday party (at a club) if he will and so starts Malcolm’s fall down a rabbit hole of drugs, guns, car chases and intrigue, accompanied, for most of the journey, by Diggy and Jib.

Although I would have liked to see more of her life apart from Malcolm, Laymons’ Diggy deserves special mention, a butch woman of color who is never a joke and doesn’t have any aspirations to be seen as tough. At the same time, she’s not a passive character: when Malcolm finds he has a bunch of molly (which back in the day was Exstasy or just “E”) that in one of the film’s turns of fancy, he is forced to sell, she’s the one who says, “”All we have to do is find the white people. Go to Coachella.” She also is the one who clips their (dull) stoner, white friend Will (Blake Anderson) on the ear every time he says the n-word, even the one time he negotiates permission. “It was a reflex,” she explains.

The film is a nice melange of an updated, John Hughes film (without the racist jokes) and early Tarantino (ditto) though the writing, while including some sharp humor in the comedic sequences, falls flat in the dramatic scenes. I should also point out that while the male characters (including the lead, Moore) are allowed to be many different shades of Black, all the women characters (save for the underused “Mom” Elise) could easily pass the paper-bag test. Still, I enjoyed the scenes with Korean American, Black model Chanel Iman as a bored rich girl, Lily. She’s a different type of femme fatale than we’re used to seeing. Shown in flimsy lingerie and topless, she doesn’t have breast implants, and she gets to shine in her later comic moments with some of the few bodily fluid jokes I’ve found funny–in any film.

Some prominent Black critics have made known their dislike of Dope, and I can guess why. The vein that runs through the plot, that even a harmless nerd like Malcolm, because of where he comes from, can’t avoid drug-running for powerful, corrupt dealers, is perilously close to what racists think about Black people in general (or Donald Trump thinks about Latinos). In an interview with Terry Gross on Fresh Air, Famuyiwa explained that he based the film on an encounter he had as a kid in his old neighborhood, accepting a ride in a drug dealer’s fancy car, only to be pulled over by the police. He wasn’t arrested (and wasn’t forced to deal drugs either), but if he had stuck to the facts in his script, this film probably wouldn’t have garnered the attention it has, including from producers Sean Combs, Forest Whitaker (who is also the narrator) and Pharrell Williams (who also wrote the film’s original songs: most of the rest of soundtrack is vintage hip-hop). Will anyone besides white guys ever allowed to be true, non-drug-dealing nerds in high school movies? Let’s hope so.

[youtube_sc url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=strEm9amZuo” iv_load_policy=”3″]

___________________________________________________

Ren Jender is a queer writer-performer/producer putting a film together. Her writing, besides appearing every week on Bitch Flicks, has also been published in The Toast, RH Reality Check, xoJane and the Feminist Wire. You can follow her on Twitter @renjender