|

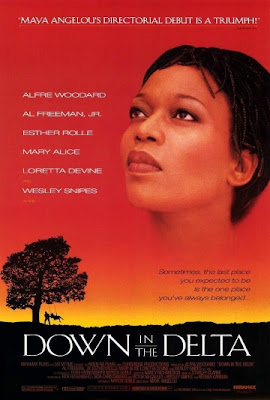

| Down in the Delta film poster. |

I love, LOVE Maya Angelou.

She is one of my favorite inspirational women of all time, and I could praise her remarkable contributions to writing and activism forever.

When I discovered that she directed only one feature film, a film I had actually seen long ago, I decided to give it another watch and looked online. Thank you, Netflix!

Down in The Delta, with a screenplay by Myron Goble, begins with Loretta Sinclair, an undereducated African American woman strung out on drugs and alcohol, raising two children in a three-generational household, and struggling to find a job in rough Chicago. Upset that she cannot answer a single mathematical equation or find a job sweeping or mopping floors at a corner store, she dives deeper into the free, alluring drug world and her mother has to save her yet again.

In films and television, the poor single mother angle never stops, and adding lack of book smarts becomes a horse beaten to death. I personally didn’t think Angelou would angle into this pigeonholed concept of minority women, but eventually Alfre Woodard turned into a “Phenomenal Woman”–just not in the most congratulatory manner.

|

| Rosa Lyn (Mary Alice) has a big idea that will keep her daughter on the righteous track. |

Rosa Lyn, Loretta’s savior of a mother, pawns off a sterling silver candelabra heirloom (which is nicknamed “Nathan”). Loretta looks at it both shocked and hungry–that notorious expression of a drug fiend knowing prize could score ample amounts of desired inebriation. Alas, Rosa Lyn only intends that Nathan be sacrificed in order to pay for bus tickets so that Loretta and her kids have a brighter future down south.

However, Rosa Lyn wants Loretta to earn the money necessary to get Nathan back in the family.

|

| Rosa Lyn (Mary Alice) pawns off Nathan the candelabra for bus tickets to Tracy (Kulania Hessan), Nathan (Mpho Koaho), and Loretta (Alfre Woodard). |

Away from tempting drugs and hardship, Earl asks Loretta to work for him at his restaurant, Just Chicken, and teaches her how to make his famous chicken sausages. She has a hard time getting it right, but eventually she does and moves onto playing a bigger role into the restaurant field. This leads to the most disappointing part of the film. She discovers purpose not just in the Delta itself, but inside of a greasy chicken sausage joint. The situation isn’t particularly humorous or exciting. In fact, speaking from a vegan standpoint, I find it pretty distasteful, especially as a climactic point. When the small town bands together to stop the closing of the chicken plant, it becomes a cheesy outstretched manifesto of people proudly boasting about their beloved meat, disregarding slaughterhouses where the most incredibly unimaginable suffering takes place–a sacrificial unwanted suffering so eerily similar to that of Jesse. Chickens are forced into small cages, plucked and boiled alive, and all kinds of other horrors before being murdered, but Angelou praises the long hindered stereotype about African Americans’ adoration of chicken. It is heard so clearly that ears start to bleed from preaching. One wonders if that passion would remain devoutly strong if fruits and vegetable crops were similarly threatened.

I’m not trying to bash the love of chicken, but the chicken and African American relationship is so difficult to handle that it in itself becomes ludicrously overdone. The closeness to joining hands and singing spirituals left behind a sour taste.

However, the story behind Nathan the candelabra serves as a better narrative and has Angelou’s signature poignancy all over the polished sentimentality. Jesse, a family ancestor, stole the valuable sterling silver antique from his former owners, an act of revenge instilled inside since age six when watching his father get sold off auction block style, as though he were nothing more than a common object, not a human being with mind and beating heart. Candelabra, named Nathan after a father Jesse never found, has been passed down to the male line, but Eddie gives it to Loretta, marking a new sense of tradition, a new entrusted foundation.

Years ago, no one would have ever considered her worthy.

|

| Loretta (Alfre Woodard) and Earl (the late Al Freeman Jr.) have much in common. |

Down In The Delta brushes on Alzheimer’s Disease and autism and beautifully weaves how family copes with the two perilous circumstances. In one of Esther Rolle’s final roles, she plays Annie, Earl’s wife. It is wonderful how much Earl cares about Annie and has overprotective need to keep her safe from harm. But he has to keep doors and windows locked, shielding Annie inside a childproof environment.

“First she couldn’t find her keys,” states Earl. “Then she forgot what the keys were for.”

Meanwhile, Tracy, Loretta’s autistic daughter, has screamed, cried, and hollered nearly the entire film, leaving terrified strangers to think her a monstrous and demonic child. In a scene after the bus arrives at a location, a distraught woman blasts Loretta’s parenting skills, blaming her for not being able to control Tracy. Everyone wonders why Loretta keeps Tracy inside of a crib, but like Earl, Loretta is protecting Tracy from endangering herself. Angelou parallels Earl and Loretta’s dealings with disease, their gnawing frustrations and little triumphs, and bridges their connection closer together. It is not romantic, but friendly, familial, and bittersweet, one that succeeds because they provide comfort to each other.

Loretta also spends time with Annie’s caretaker, Zenia who offers her beer. Now Loretta, appearing uncomfortable and noticeably silent, could have easily declined. Alcoholism is a real disease to master and for her to suddenly kick back and have a chuckle makes light of the real difficulty people have just being around a bottle–having one little drink (or in this case, a whole bottle) is downright impossible.

The late Roger Ebert, however, was one of several critics who enjoyed

Down in the Delta:“Angelou’s first-time direction stays out of its own way; she doesn’t call attention to herself with unnecessary visual touches, but focuses on the business at hand. She and [Myron] Goble are interested in what might happen in a situation like this, not in how they can manipulate the audience with phony crises. When Annie wanders away from the house, for example, it’s handled in the way it might really be handled, instead of being turned into a set piece.”

Down in the Delta ends with the “feel good” message that life can be filled with turmoil and can appear inescapable, especially to a minority woman, but it’s never too late to turn things around. After Nathan is “rescued” from the pawn shop and handed down to Loretta, everyone now trusts her, the threat of drugs/alcoholism disappears, and Earl promotes her to running Just Chicken so that he can spend more time with Annie. Loretta now has reached a positive place.

As director, Maya Angelou’s spirit floated between the Mississippi-centered delta, but sometimes drifted away like it was never there.

However, that doesn’t mean that I don’t want her to make another film.

In fact, I wish she would.