This guest post by Stephanie Charamnac appears as part of our theme week on Asian Womanhood in Pop Culture.

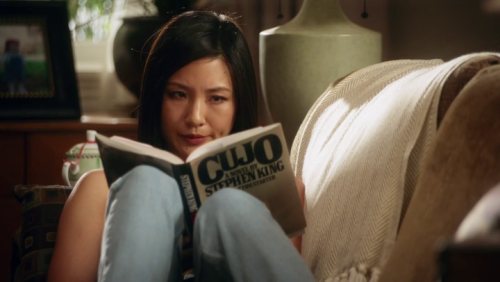

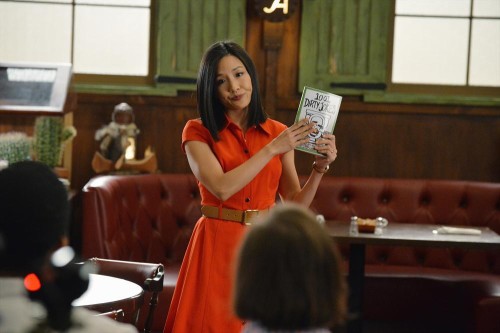

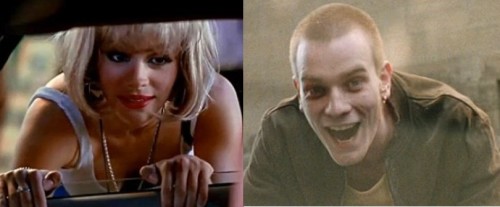

When The Social Network came out in 2010, critics heaped effusive, almost rapturous praise on the film. Rolling Stone hailed it as “bracingly smart, brutally funny and acted to perfection,” while the New Yorker called the movie “absolutely emblematic of its time and place.” Amidst all the hype, one less than glowing aspect of The Social Network went virtually unnoticed: its blatantly stereotypical portrayal of Asian-American women, as epitomized by the character of Christy Ling. Christy, played by Brenda Song, has a minor role in the film and appears onscreen for no more than twenty minutes. But in this short space of time, she is depicted as the ultimate hypersexualized, exotic and aggressive Asian girlfriend – a hybrid between Dragon Lady and China Doll.

The first time we see Christy in the film, she is in full seduction mode. Dressed in a cleavage-baring top and short skirt, she approaches Eduardo Saverin (the co-founder of Facebook) during a college lecture. When she realizes that he is Mark Zuckerberg’s friend, she immediately suggests that they all go out for drinks. A few minutes later, Christy and Eduardo are shown in a bathroom stall, with Christy performing oral sex. In this scene, she is every bit the Dragon Lady – aggressive in her sexual advances and confident in her own “exotic” charm. After this encounter, Eduardo tells Mark smugly: “We have groupies.” Within the first few minutes of appearing in the movie, Christy has already been established as a sex-crazed gold digger.

Although Christy is sexually aggressive, she is portrayed as being passive and quiet in later scenes. One notable instance is when she and her friend (another Asian woman) are sitting on a couch in Mark Zuckerberg’s room, listening as the male students discuss their plans for Facebook. When Christy asks if they can do anything to help, Mark simply responds “No.” Unfazed by his dismissive attitude, she continues drinking on the sofa – casually accepting the fact that she has no role to play in this powerful men’s club. A similar scene unfolds when Mark, Eduardo, and Christy meet up with Sean Parker, the founder of Napster, in a restaurant. Although Christy is the one who set up this meeting, she is again relegated to the background when the three men start talking. Every time the camera pans in her direction, she is shown listening raptly to Sean Parker, deferring to his opinions. At no point in the scene does she make a meaningful contribution to the business meeting. Her function is purely decorative. All that is asked of Christy is for her to behave like a beautiful, silent China Doll – a role that she executes perfectly.

But for her final scene in the film, Christy suddenly switches back to full Dragon Lady mode. Seething with jealousy and suspicious that Eduardo is cheating on her, she ends up setting fire to the gift he gave her (a scarf), and dumping it in the garbage can. In her last moments onscreen, she epitomizes the “crazy bitch” trope, with plenty of Dragon Lady-style villainy for good measure. It seems that her character can only exist at opposite ends of the spectrum – either hyper-aggressive or doll-like in her submissiveness. This leaves no room for complexity or insight into her behavior; she is merely a caricature, and not a fleshed-out person.

Thus, Christy appears to be more akin to an object than a real character in this film. She is supposed to be a Harvard student, but there is no intellectual dimension to her portrayal: her body is the only thing on display, readily available for the visual and sexual pleasure of white men. Part Dragon Lady, part China Doll, Christy is 100 percent stereotypical. It’s hard to believe that such a distorted representation, steeped in age-old myths, only dates back to 2010. Even more disheartening is the fact that most film critics did not raise an eyebrow at this deeply flawed portrayal.

In their gushing reviews of The Social Network, critics from the New York Times, Washington Post, USA Today, and Los Angeles Times did not once mention the film’s stereotypical treatment of Asian-American women. The Boston Globe noted the movie’s lack of strong female characters, but merely as a passing comment instead of a real critique. Even The Harvard Crimson had nothing but praise for a film that essentially objectifies all of Harvard’s female students. The reviewer called The Social Network “a stunning modern epic” and deemed it an “authentic onscreen representation that captures the general tone of the [Harvard] campus.” This glaring lack of critical insight underscores what is perhaps the most dangerous aspect of widely circulated stereotypes: they often appear so “normal” that they are taken for granted.

Rebecca Davis O’Brien’s review for The Daily Beast offered one of the rare instances where a critic from a major news website took issue with The Social Network. O’Brien commented that “missing from what critics are calling the defining story of our age are female characters who aren’t doting groupies, sexed-up Asians [or] vengeful sluts.” The fact that most of the mainstream media outlets failed to notice or question the film’s problematic representation of Asian women indicates the extent to which Dragon Lady and China Doll stereotypes still permeate the entertainment industry.

This vicious cycle can only be broken when mainstream media portrayals start to acknowledge that Asian women are real people, and not hypersexualized objects of lust. Media producers – especially those in Hollywood – need to realize that these harmful images only serve to perpetuate racial prejudice and ignorance. If we really want to move into the 21st century, it is time to banish the ghosts of the Dragon Lady and the China Doll from our screens once and for all.

Stephanie Charamnac is a freelance writer and editor living in Singapore. She holds an MA in Media & Communication from NYU, which is just a fancy way of saying that she’s obsessed with all things pop culture.