Written by Rachael Johnson.

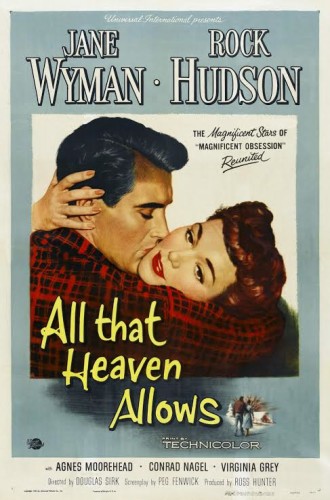

Directed by Douglas Sirk, All That Heaven Allows (1955) tells the romantic tale of Carrie Scott (Jane Wyman), an attractive, wealthy middle-aged widow who falls in love with a young landscape gardener. The object of her affection, Ron Kirby (Rock Hudson), is a handsome, brawny man in his late 20s or early 30s. He is the very opposite of Harvey (Conrad Nagel), a dull, older suitor Carrie politely tolerates. Carrie, in fact, spends a lot of her time alone although she has two grown children, Ned and Kay. Kay (Gloria Talbott) is a geeky, pretty social work student who loves to share her interest in psychoanalysis with others, even with her dim, sporty boyfriend. As with most ’50s American films, her intelligence is indicated by spectacles. Her brother, immaculately attired, handsome Ned (William Reynolds), loves to make martinis and control people. The other important person in Carrie’s life is her best friend Sara (Agnes Moorehead). She is a bit of a snob but comparatively nicer than the rest of the country club types who populate Carrie’s social life.

Ron Kirby comes from a very different world. He leads a natural, comparatively free, non-consumerist life in the woods. His friends are bohemian types and they too have renounced the reigning materialistic ethos of their place and time. When Carrie is introduced to them, she revels in their warm, unaffected ways. Unsurprisingly, it doesn’t turn out too well when Carrie presents Ron to her friends, after announcing their plans to marry. When they’re not disparaging his tan or calling him “Nature Boy” behind his back, they’re mocking his socioeconomic status, and lack of materialistic ambition. It is the children, however, who will force Carrie to give up Ron, for the sake of family, propriety and property. She sacrifices her love for him for her children and convention but soon comes to regret it. Kay becomes engaged and Ned, hoping to study in Paris and work overseas, thinks it would be better to sell the house as it would be too big for his mother. As Carrie acknowledges, “The whole thing’s been so pointless.” A near-tragedy, however, thankfully brings the lovers back together in the end.

All That Heaven Allows is a deeply involving, and satisfying love story. Love stories are always, of course, more powerful when the lovers are faced with barriers to love, and when the romantic and erotic ache is painfully but pleasurably acute. Sirk provides a potent emotional and sensorial experience with All That Heaven Allows. Filmed in Technicolor, the hues of both the natural and human-made objects on the screen have a gorgeous, Expressionist intensity. Some of the film’s images are both over-the-top and wondrous. There is even a Disneysque deer that Ron feeds in winter. True to melodramatic form, he falls off a cliff, and suffers a concussion just when you think the lovers are on the verge of a reunion. All That Heaven Allows has, also, more subtle moments and images, in terms of narrative and style. Sirk’s mastery of shot composition is, equally, always evident.

But All That Heaven Allows is not just a good-looking, affecting melodrama. It can be enjoyed on many different levels. In both indirect and observable ways, Sirk’s weepie targets oppressive aspects of post-war America. For some time now, both film critics and scholars have, understandably, foregrounded the socio-political uses of Sirk’s powerful, immoderate film-making style, as well as the subversive elements in his melodramas. They, in fact, invite socially and gender-aware readings. Filmmakers too, like Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Todd Haynes have also found Sirk’s work stimulating and inspiring. Far From Heaven (2002) and Ali: Fear Eats The Soul (1974) both draw from All That Heaven Allows.

All That Heaven Allows can be interpreted, and enjoyed, as an empathetic critique of female alienation in post-war America. Carrie is presented as the ideal, upper middle-class WASP woman of the ’50s–elegant, gracious, attractive, but not too sexual, as well as, of course, loving and maternal. But there is something missing. Carrie feels empty and trapped. Lifeless even. The metaphor that describes her state is first used by her daughter earlier on in the movie when she marvels at the stylish, comparatively sexy red dress her mother puts on for a date with Harvey. Her mother should enjoy herself, she asserts, before elaborating: “Personally I’ve never subscribed to that old Egyptian custom of walling up the widow alive in the funeral chamber of her dead husband along with his other possessions.” Kay will, of course, contribute to her mother’s metaphorical walling-up later on. It’s an Orientalist image, of course, but it’s used here to criticize post-war American patriarchy, particularly its puritan need to control female sexuality. When Kay adds that the custom does not exist anymore, her mother quietly replies, “Well perhaps not in Egypt.”

People–both men and women–make deeply personal, gendered assumptions about Carrie. In fact, they’re constantly telling her what she feels and what she wants. Men try to control her sexuality. Even harmless, old Harvey feels he has the right to tell her that she doesn’t really want romance at this stage. “I’m sure you feel as I do that companionship and affection are the important things,” he says. Her own son tries to regulate her sexuality. When Ned first sees that red dress, he tellingly remarks that it’s “cut kind of low.” More on him later. As the sexual target of a sleazy, married man, Carrie is also the object of more demonstratively misogynist control.

All That Heaven Allows takes aim at the nuclear family too. The grown-up kids are appalling. Her daughter thinks she’s hip but she’s as cowardly and conventional as the rest of Carrie’s loved ones. Ned’s a controlling, priggish prick. Kay does apologize for her behavior in the end but even so. In fact, the more you reflect on their efforts to shape their mother’s fate, the more sinister they seem. Her love for Ron represents a new start, a new life, new experiences, but they want her to give up her happiness and surrender her very self. The nuclear family–trumpeted in the ’50s (and even today)–as the be-all-and-end-all of human social units–is shown to be a sick little institution. Her son wants to the kill the love and desire his mother has for this tall, handsome, younger man. Kay playfully alludes to her brother’s Oedipal complex but he’s the real deal. Ned is outraged that his mother’s mate, and potential step-father, is “a good-looking set of muscles.” Ned buys a big-screen TV for Carrie. The television means safe, comfy company, of course. The message is clear: Get your slippers on, Mom, and watch The Ed Sullivan Show. No more pleasure, no more drama, no more love for you. Sit back and sacrifice your life. Watch other people living theirs. He may be young but he’s a true blue patriarchal asshole in the making. He’s also a zealot of the dominant consumerist, classist order.

All That Heaven Allows does address and critique American materialism and classism in a considerably direct fashion. The United States was fast becoming an unapologetically consumerist society in the ’50s. It is what drives nearly everyone around Carrie–apart from Ron and his happy lot. His lack of interest in money is the subject of conversation of the country club set. In his world, Carrie learns about another way of living. The materialist, consumerist life is clearly understood here as a conformist trap. Their spiritual guide is Thoreau. Carrie’s situation is particularly interesting, of course. She is the embodiment of privilege and the ideal consumer, but something is not right. Her alienation is spiritual as well as gender-specific. She is attracted to a different way of being. She does not just fall in love with Ron; she falls in love with his world too.

It’s a pleasurable sport analysing the socially subversive elements in All That Heaven Allows. What’s equally interesting, and gratifying, is spotting, and reflecting on, the historical setting, what is obscured and what is unsaid. The first time I watched it, my thoughts drifted, now and again, to what was going on in America and the world in the mid-fifties. The decade is generally described as a period of confidence and prosperity for America. For White America that is. For Black Americans, it was another story, of course. All That Heaven Allows was released in 1955. It was the year that 14-year-old Emmett Hill was murdered and mutilated in Mississippi and the year that Claudette Colvin and Rosa Parks protested bus segregation laws in Montgomery, Alabama. Carrie’s peers do not speak of race. They are not only complacent, narrow-minded products of their age and class; they are also profoundly insular and provincial. There is no talk of Russia and the Cold War either. They are blind to their own nation’s troubles and seem ignorant of the U.S. government’s neo-imperialist involvements in other lands. It is an interesting, yet unsurprising, thing that Ned plans to take up a post in Iran following his Paris scholarship. The American government had already, in fact, paved the way for him. In 1953, the CIA, and the British, got the democratically-elected leader of Iran, Mohammed Mossadeq, ousted in an engineered coup. (He had nationalized the Anglo-Iranian oil company). The CIA finally admitted to its involvement in 2013. You just know Ned’s real-life version would go on to do very well for himself in the latter part of the 20th century. The unthinking, self-interested corporate type Ned represents is the future.

There is so much else to contemplate and admire in All That Heaven Allows. Jane Wyman gives an exquisite performance as Carrie. It’s a deeply sensitive, insightful portrayal, and we empathise entirely with our heroine’s situation. Wyman conveys her joys and fears beautifully, both the stabs of jealousy Carrie suffers when she fears Ron desires another woman, as well as the feelings of excitement she has when experiencing another way of life for the first time. Rock Hudson is less interesting but charming, and handsome all the same. Most crucially, he represents the promise of something new. The lovers are both good and gracious people, and the actors effectively capture their nobility and kindness as well as the gentle, tender nature of their love. Wyman and Hudson have considerable chemistry. Incidentally, All That Heaven Allows wasn’t the first time the actors had worked together in a Sirk movie. They had been successfully paired the previous year in Magnificent Obsession (1954).

All That Heaven Allows is also ravishing to look at. Visually, it is both intense and inventive. There are some pretty arresting images. Perhaps the most striking, and disturbing is that television Carrie’s kids buys for her. It may be the ultimate symbol of American consumerism and modernity in the mid-fifties but it quite horrifically embodies materialism, conformity, and alienation in All That Heaven Allows. It’s no exaggeration to say that for Carrie it represents a death-in-life existence. It is no less a symbol of oppression and mortality than the Egyptian widow’s tomb Kay talks about earlier in the movie. Although she has to surmount obstacles of convention and chance, Carrie will, thankfully, in the end, resist its darkness. For In All That Heaven Allows, female romantic love is a form of light, liberation, and resistance.