Guest post written by Katherine Filaseta.

It is no secret that India has problems when it comes to the status of women. Everyone heard about the gang rape in Delhi in December 2012; it was broadcast in America so much that some people didn’t even know about the events in Steubenville, but knew all about India. There is a common perception in America these days that women in India are seen as “sub-human” by all of Indian culture, and this is entirely false. However, it is true that I do not feel safe being a woman and walking down the streets of India alone, and this is a problem.

I adore Bollywood; it allows me to watch an entire generation evolve on the silver screen, no matter what country I’m currently living in. I even love the fact that some Bollywood love stories are more romantic than the sappiest fairytales. However, some of these love stories come with the price of reinforcing terrible patriarchal standards – and any story that makes sexual harassment appear commonplace and “okay” isn’t romantic, no matter how charismatic the leading man is.

Which Bollywood films become hits and which become flops can be indicative of which values Indian society places the most importance on. Perhaps if the right films are successful, the next time I go to India I’ll feel safe walking down the street alone – maybe even at night. Safety for women doesn’t have to be some elusive fantasy, and Bollywood can help us create this change.

Terrible Films That Everyone Loves

There are a lot of films in India which have been wildly successful, but which have also been detrimental for the feminist agenda in India. All of the films that follow are in this category. These three films together encompass all three major Bollywood stars and are on the must-watch list for anyone interested in Bollywood. I am also convinced that every single one of these films has played a role in shaping the way Indian society thinks, making it more difficult for women to live safely and comfortably in India.

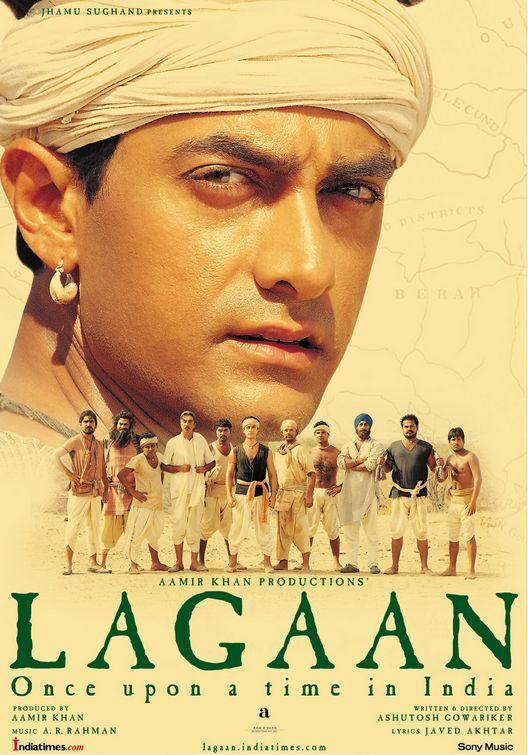

|

| Shah Rukh Khan and Kajol in Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge |

Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge, 1995

To give you an idea of just how wildly successful DDLJ is: it has been running in some theaters for 900 weeks straight as of January 11, 2013. People love this film. Shah Rukh Khan plays Raj, a charming douchebag; Kajol plays opposite him as Simran and is stunning and loveable as usual. It is one of the first films to address the problems that affect NRI’s (Non-Resident Indian, or Indians living outside of India), as well as the conflict of “tradition vs modern” faced by Indians in the 1990s as everyone tried to reconcile their family’s values and traditions with the growing influence of Western culture – and it does an amazing job portraying each.

What it also does, though, is help to solidify a patriarchal standard. This film tells people, through the love story of Raj and Simran, that with enough persistence, harassment, and stalking, a man can convince any girl to fall in love with him. A girl is a prize to be won, and sexual harassment is the way to win her. Not only that, but the ultimate way to show respect for a woman is by refusing to marry her until her father literally hands her over to you – solidifying the female’s complete lack of choice in the scenario.

(Spoilers follow the images)

|

| How Simran feels about Raj before intermission |

|

| How Simran feels about Raj after intermission |

Raj spends the entire first half of the film harassing Simran non-stop throughout Europe. They are trapped together in the most unfortunate of circumstances, but Simran remains wonderfully strong. Soon, however, Raj professes his love for Simran – and she, apparently suffering from some sort of Stockholm Syndrome, returns his love. However, Simran and Raj can’t be together; Simran has already promised to follow through with a marriage her parents have arranged for her back in India.

Raj follows Simran to India, but they can’t just run off together. Simran has been won and is willing to leave her family behind forever to spend her life with Raj, but unfortunately for her Raj still has another challenge to complete before he can run off with his prize. Simran is still owned by her father, and Raj is too decent to steal an object from another man. He has to convince Simran’s father to give her to him, and so commences the second half of the film. Of course it turns out well for the couple, as after and hour and a half of convincing and fifteen minutes of dramatic tension, Simran’s father literally allows her leave his hands and run into Raj’s.

Every single line used by Raj in his harassment of Simran over the course of this film has also been used on me in India. By Raj succeeding in marrying Simran, her discomfort at his harassment is transformed into simply a girl playing “hard to get”. DDLJ has helped shape my coarse response to similar harassment into nothing more than encouragement for men to try harder.

|

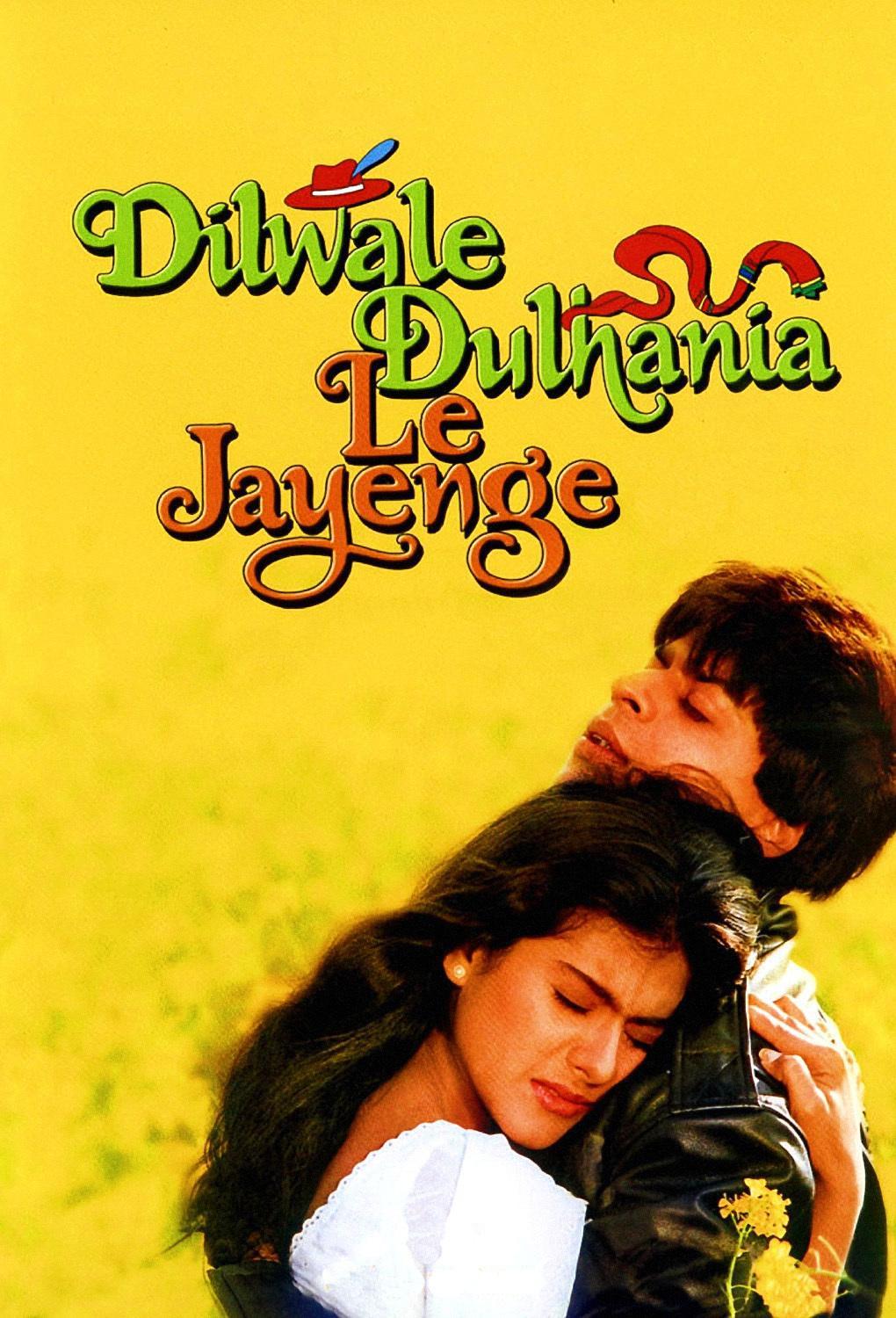

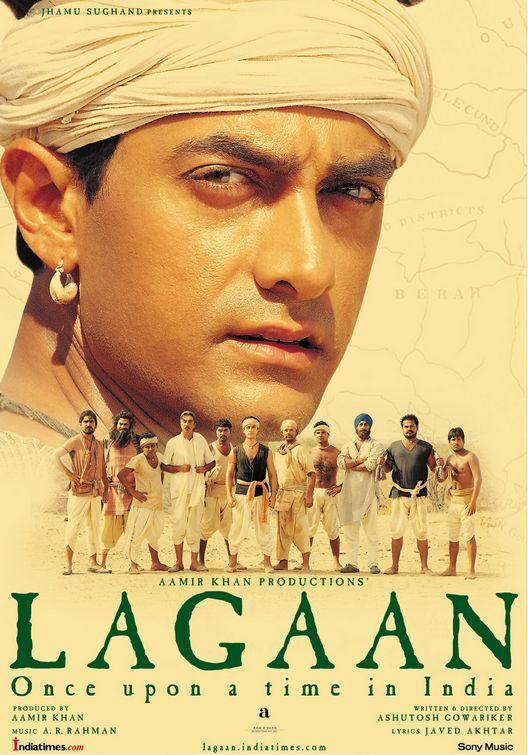

| Aamir Khan in Lagaan |

Lagaan, 2006

Lagaan is only the third film out of India to be nominated for an Oscar. It didn’t win, but it put India on the map for the first time since the 1980’s as a place where legitimate films are made. It is set during the British Raj, where an insufferable British officer is abusing his power over the local villagers by imposing a land tax they can’t afford to pay. They end up placing a bet over a cricket match: If the villagers, with a strong-headed patriot named Bhuvan at the lead, can learn the game and defeat the British officers, they will not have to pay the tax. It is a very well-made film starring Aamir Khan, who is known in India for fighting for social change across the country.

There are a lot of good things about the film, and it deserves most of the positive attention it has garnered. However, there is a major problem with the film as well: there are only two female characters, and both of them serve the sole purpose of fawning over the male lead. Elizabeth Russell is a very kind British woman who sneaks out of her house to teach the villagers the game of cricket, despite the language barrier and opposition from her family. Essentially, the instant she meets Bhuvan, she forgets her greater purpose of helping the fight against injustice and falls head over heels for him. She even professes her love for him, but of course Bhuvan can’t speak English so doesn’t understand what she is saying. Elizabeth’s opposition is Gauri, a village girl who is also in love with Bhuvan, but who has never told him. She has, however, shown her love through making him rotis, as any good Indian wife should. (Spoiler alert ahead!) In the end, Bhuvan marries Gauri and Elizabeth moves back to England to be single for the rest of her life.

|

| Elizabeth Russell singing about how much she loves Bhuvan |

|

| Gauri singing about how much she loves Bhuvan |

In a typical move of exoticizing the other, there is a common stereotype in India of white or “Westernized” women being sexual to the point that they have already given their consent for anything a man might want to do to them. We did the same to them by popularizing and exaggerating the kama sutra, so you can’t blame them too much – but by creating Elizabeth Russell, this stereotype is only being reinforced. White women clearly all come to India for the sole purpose of falling in lust with men they can’t even communicate with, but Indian women shouldn’t worry – men will always marry the proper Indian girl who makes delicious rotis in the end.

|

| Salman Khan in Dabangg |

Dabangg, 2010

I could have easily and accurately instead said “every movie starring Salman Khan in the past few years,” but Dabangg was the beginning of the movement. I was in India when Dabangg came out, and the excitement over Salman Khan’s comeback film was pervasive and insane. This is a ridiculous film starring a man who epitomizes a certain standard of masculinity: Chulbul Pandey has bulging muscles, a propensity for fighting, and an ability to woo girls by harassing them until they fall in love with them (a la DDLJ). Chulbul Pandey’s signature dance move is the hip thrust, and he uses it every chance he can get.

If Dabangg did anything right, it was play to Salman Khan’s strengths. This is a man who has gotten away with killing a man while driving drunk, and who has a restraining order placed against him by his ex-girlfriend whom he used to physically abuse. He was the first Bollywood star to really “bulk up,” which has helped him win over a few of the most lusted-after Bollywood starlets. Chulbul Pandey has testosterone flowing in every inch of his body, and Salman can play this character perfectly.

There are essentially two females in this movie: the one Chulbul woos by harassing her until she feels she has no choice but to marry him, and an item dancer – a girl whose sole purpose is to appear in one song wearing close to nothing while a bunch of drunk men (Chulbul included) fawn over her oozing female sexuality. Other Salman Khan films since, including the Dabangg sequel, haven’t been any better.

|

| Mallika Sherawat dancing her item number, “Munni Badnaam Hui” |

(For a well-written, feminist perspective on Dabangg 2, see Priya Joshi’s review for Digital Spy)

Is There a Bright Side?

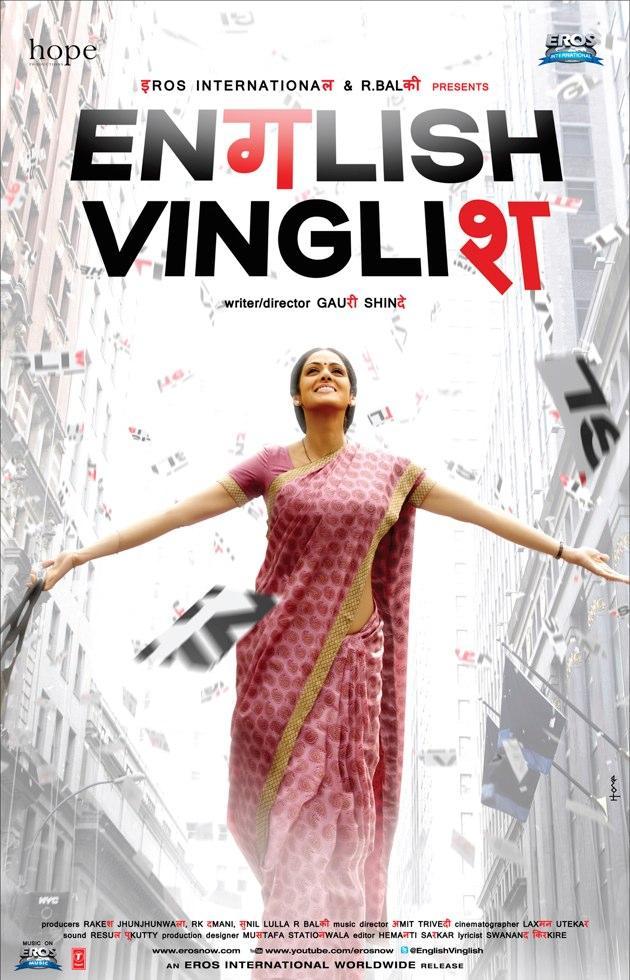

For the most part, last year was a great year for Hindi films. February gave us Ek Main Aur Ekk Tu, winning the feminist audience over with its ending, in which the central relationship is left to proceed on the girl’s terms. March gave us Kahaani, an amazingly well-made movie with a strong, central female character. In October, we were brought something amazing through English Vinglish: a female-directed film with a strong female lead, which beautifully addresses some of the issues middle-aged Indian women are facing both in India and abroad. Previously, the cut-off age for female leads in Bollywood has been around 30, so Sridevi’s starring role in this film in itself is an additional breakthrough on the feminist front.

I haven’t watched anything promising yet in 2013, but given the success of more progressive films in 2012, we can remain optimistic. In Mera Naam Joker, there is a female character named Meena who pretends to be a man and carries a knife, which she pulls out at the tiniest threat to her safety – simply so she is able to live alone in Bombay. Even though this film is over 50 years old, I have spent a lot of time myself wondering if I could pull off what Meena did. The situation now isn’t much better, but it can be. We can control our own future as women in India, and Bollywood can help us – not just hold us back.

Katherine Filaseta is a recent graduate of Washington University in Saint Louis whose life has somehow managed to become constantly split between the United States and India. She really likes Bollywood, education, feminism, zoos, and the performing arts. Follow her on twitter.

Seriously reaching here, I’m afraid

Thank you for this post. Looks like three great options, and they’re all streaming on Netflix right now!