This is a guest review by Amanda Civitello and is published with permission. Note: this review contains no spoilers for Season Three.

“Christmas at Downton Abbey” (The Christmas Special). Downton Abbey: Season Two Original UK Edition. Writ. Julian Fellowes. Dir. Brian Percival. Masterpiece Classic/PBS Distribution, 2012.

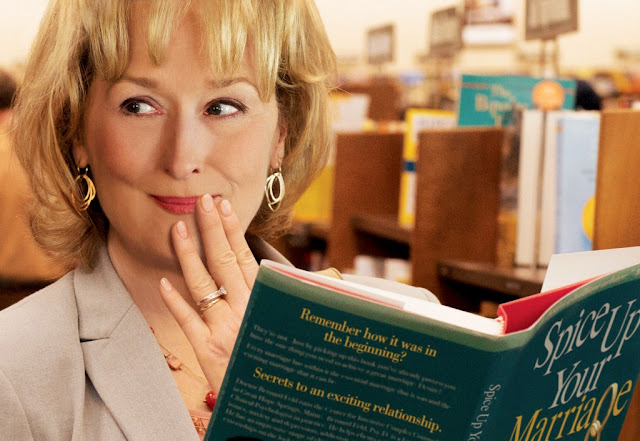

|

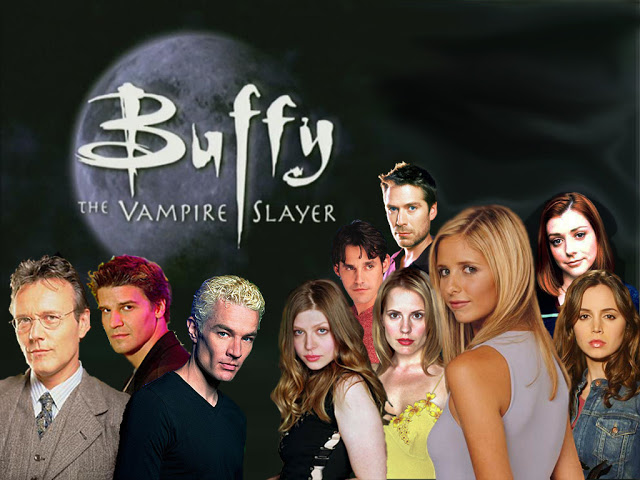

| The cast of Downton Abbey |

The Emmy-nominated second season of Downton Abbey opened with its characters on the precipice of the destruction of their rarified pocket of Edwardian English aristocracy, with the Great War at Downton’s doorstep. [i] The season’s final episode, “Christmas at Downton Abbey,” submitted as part of the PBS Masterpiece 2012 Emmy campaign, mostly avoids talk of social upheaval in favor of returning to the human drama that was so popular in the first season. The Great War, explored at length during the second season, has already wrought significant – though frequently indirect – change at Downton Abbey. Youngest daughter Lady Sibyl, who trained as a nurse during the War, is now married to the family chauffeur-turned-Republican-journalist and at home in Ireland for Christmas; heir apparent Matthew’s fiancée Lavinia has succumbed to Spanish flu, having outlived her usefulness once Matthew recovered from his battle injuries; and Lord Grantham’s wealthy, widowed sister Lady Rosamund has brought home a new beau for the holidays – and that’s just the news from upstairs.

Lady Rosamund’s narrative thread plays second fiddle to the episode’s main concerns, the murder trial of Lord Grantham’s valet, John Bates, and the imploding engagement of eldest daughter Lady Mary to newspaper magnate Sir Richard Carlisle. The tempestuous and controlling relationship between Lady Mary and Sir Richard is worthy of an in-depth feminist critique, but because its development occurs over several episodes, it’s not feasible to do it justice in this piece. However, the Christmas special’s treatment of Lady Rosamund and her love interest, fortune-hunter Lord Hepworth, encapsulates most concisely the paternalistic, patriarchal society in which they lived. Moreover, Lady Rosamund’s story serves as a useful way to begin a discussion about the way that Downton Abbey portrays two of the senior ladies of the family: Lady Rosamund and her sister-in-law, the Countess of Grantham.

In the first and most of the second seasons, Lady Rosamund is essentially a plot device who interferes in her nieces’ lives and runs reconnaissance for her mother when necessary to move the story along. Fortunately, the considerable talent of Samantha Bond rescues the character from marginalized oblivion. Lady Rosamund is compelling, even when her scenes don’t contain very much for her to do. There’s a complexity and nuance to Bond’s performance that makes Lady Rosamund someone worth caring about, in part because she’s an actor who makes excellent use of her voice. She’s very much like Maggie Smith in that respect: they are both cognizant of the voice as a flexible, powerful instrument and exercise it accordingly.

“Christmas at Downton Abbey” finally gives Lady Rosamund a storyline of her own, and one worthy of Bond’s thoughtful portrayal. Lady Rosamund’s suitor’s family fortune is so diminished that, as the Dowager Countess of Grantham puts it, “he’s lucky not to be playing the violin in Leicester Square.” Indeed, Hepworth only apprises Lady Rosamund of his dire financial straits at the insistence of the Dowager Countess. “I’m tired of being alone,” Bond’s Lady Rosamund says, and the brilliance of the portrayal is that she sounds exhausted; there’s only the barest glimmer of enthusiasm for a new romance. Lady Rosamund acquiesces to the best future she thinks she can buy: heartbreakingly, she adds, “And I have money.” In Bond’s hands, Lady Rosamund doesn’t sound desperate, as her words would suggest; rather, she’s resigned to an unfortunate, uncomfortable reality. She knows how society values her – and it’s not for her intrinsic merits, but rather for her late husband’s considerable fortune. She’s shrewd: she knows she’s entering into a business arrangement as much as anything else, but she’s motivated by her desire for a partnership as well. When she catches Hepworth bedding her maid, Shore, Lady Rosamund is certainly stung by the betrayal: “I just can’t stand it when Mama is proved right,” she declares, bitterly. She knew he wanted her for her money; she simply dared to hope for more.

But Lady Rosamund is not the only person charting her course. Unbeknownst to her, her mother and brother discussed the match and its ramifications before she discovers Hepworth’s duplicity. “Is a woman of Rosamund’s age entitled to marry a fortune-hunter?” the Dowager Countess asks her son. Yes, he concedes, providing she’s been made aware of the circumstances, “but for God’s sake, let’s tie up the money.” It’s clear that Lady Rosamund finds herself trapped in a gilded cage. She is twice damned: as a widow, she’s essentially passed back to her family, who permit her to make significant life decisions; and despite the independent image she presents, the final say regarding her finances rests with her brother.

|

| Lady Rosamund and her beau, Lord Hepworth |

Of course, it’s not a personal slight against Lady Rosamund. The paternalism that Lord Grantham exhibits (and that his mother defends) isn’t the fault of the show: Downton Abbey is, after all, a historically-minded serial; writer Julian Fellowes can’t help the prejudices of the time period. While there’s historical precedent for a woman in Lady Rosamund’s position, the show is fictional and so functions within its own universe, with its own rules. We can watch with an eye toward parallelisms because the world of Downton Abbey is a carefully crafted one, and contrasting Lord Grantham’s handling of his own history and his sister’s nascent romance invites the viewer to realize the prevalence of paternalism in aristocratic families. It’s not accidental that Lord Grantham himself was a fortune-hunter actively searching for a bride wealthy enough to rescue Downton Abbey. The Countess of Grantham and Lady Rosamund are commodities, and their value is their net worth. Lord Grantham doesn’t much mind what his sister does with her affections so long as her money is tied up; some thirty years earlier, he didn’t much mind who he married so long as she balanced his accounts. Julian Fellowes’s use of parallelism in the narrative is shrewd: we discuss these issues because of the way he chooses to tell the story.

That’s not to say that Fellowes is waving the feminist flag; he’s not. He’s in the business of writing well-crafted, witty scripts that tell a good story and maintain as close a degree of fidelity to the historical record as possible. The choices he makes as the writer are entirely to that end. Sometimes, they’re pro-woman, whether in a roundabout way, as in asking the audience to consider what life used to be like, or in a more explicit manner, such as Sybil’s interest in woman’s suffrage and ambition to work and pursue a more autonomous life for herself.

In other instances, however, the show shies away from the most challenging of its subplots. The Christmas special is notable for the storylines which it does not address, and the three most prominent of these concern women: the unresolved question of Lord Grantham’s infidelity; Lady Grantham’s sense of purpose derived from running the hospital housed in her home during the war; and the inter-class intimacy that develops between Lady Grantham and her lady’s maid Sarah O’Brien following the former’s miscarriage in the season one finale.

The first two missed opportunities are linked: as presented in the season, Lady Grantham finds such meaning in her work for the hospital during the war that she initially can’t contemplate returning to her old life of attending to her social obligations. Her husband bristles at her newfound direction, which means she has less time for him. During the seventh and eighth episodes, his flirting with a housemaid, Jane, becomes more and more serious, culminating in an encounter halted only by the precipitous interruption of Lord Grantham’s valet. After Bates leaves, Lord Grantham seems to have reevaluated the situation and remembered his marriage vows – and the fact that his wife is next door, gravely ill with the Spanish influenza.

These two storylines, though linked, fail in their portrayal of women in different ways. In the instance of Lady Grantham’s independence, her narrative simply peters out. In the penultimate episode, Lady Grantham apologizes for “neglecting” her husband; by the Christmas special, she has happily returned to playing lady of the manor, worrying over whether there’s sufficient time to change for dinner.

The apology in question occurs just after Lady Grantham’s brush with death; in response, Lord Grantham simply says, “Don’t apologize to me.” But refusing her apology doesn’t absolve Lord Grantham of his guilt; nor does he seem to have any inclination to admit his indiscretion to his wife. From a feminist perspective, this is a perplexing editorial decision. The script allows Lady Grantham’s apology to stand, because she wasn’t the wife she was supposed to be. He might not accept it, but she’s the one who says the words. Lady Grantham’s tentative steps toward greater independence are immediately retracted; she apologizes for it. In a drama serial that deals primarily with interpersonal relationships, there’s no compelling reason to not address Lord Grantham’s infidelity. In the end, it’s Lady Grantham who’s punished and corrected.

The other missed opportunity in the “Christmas at Downton Abbey” concerns Lady Grantham and her lady’s maid, Sarah O’Brien. In the last episode of the first season, O’Brien’s anger at Lady Grantham’s perceived slight takes a fateful turn when she deliberately endangers her mistress and inadvertently causes Lady Grantham to miscarry. Throughout the second season, then, O’Brien channels her guilt into taking extraordinary care of her mistress; their relationship is characterized by increasing complicity and mutual affection. It is O’Brien who nurses Lady Grantham through her grave bout with Spanish influenza. The overtures of friendship are never quite realized, however, and O’Brien’s touching, climactic scene in which she asks Lady Grantham’s forgiveness occurs when the latter is delirious with fever. Having made the affection she feels for her mistress readily apparent (Mrs. Patmore, the cook, comments on it), O’Brien’s devotion is even acknowledged by Lord Grantham, who actively dislikes her. The Christmas special, however, never addresses the issue at all. It’s a missed opportunity to consider female friendship within a socio-economic context: after all, O’Brien has waited exclusively on Lady Grantham for over fifteen years, resulting in a curious master-servant relationship marked by necessary affinity and learned intimacy. Their tentative steps towards greater familiarity would be an interesting avenue for the show to explore, given the increasing social mobility that’s on the horizon. The fact that the storyline is wholly ignored in the Christmas special is disappointing.

Indeed, the lack of female friendships is a curious omission in Downton Abbey. There is minimal complicity between the main upstairs female characters: most relationships are marked by outright dislike or disinterest. It’s disconcerting; these ladies who are perfectly charming, each and all, around men, but who seem to lack any kind of amity with other women. When moments of camaraderie do come, they are typically between the ladies and their maids: Lady Sybil befriends Gwen, a housemaid, in the first season, but Gwen leaves Downton; eldest daughter Lady Mary has an affectionate relationship with her maid, Anna, that’s similar to her mother’s with her lady’s maid. What renders the dearth of female friendship so extraordinary is that it would have been unusual at the time. [ii] By rendering women either objects of desire or economic necessity, and essentially presenting them only vis-à-vis men, Downton Abbey doesn’t engage with its female characters as fully-realized people. They only rarely step outside of a male-defined paradigm, and when they do, they’re inevitably walked back. Gwen leaves Downton, content with her new job; Lavinia dies on the cusp of a budding friendship with Mary (complicated, of course, by Mary’s continued affection for Lavinia’s fiancé); O’Brien cries bitter tears at her mistress’s bedside and is treated no differently from anyone else on the receiving line for the staff’s obligatory Christmas presents.

|

| Lord Grantham and the Dowager Countess discuss Lady Rosamund’s finances |

Ultimately, the lens of patriarchy influences the female characters’ understanding of their self-worth. Lady Grantham tells her daughter that she’s “damaged goods” in the first season after Lady Mary loses her virginity to a handsome, rogue diplomat. Initially we bemoan Lady Grantham’s inability to empathize with her daughter’s plight. As the series progresses, that opinion begins to change. By the Christmas special, when Lady Grantham’s steps to independence have been halted by her husband, it’s possible to see that early scene with Lady Mary in a new light: if Lady Grantham understands her daughter’s worth to be entirely wrapped up in her virginity (read: her marriageability), what does that say about her own sense of self? Julian Fellowes’s tendency to return to similar themes in new contexts enables his audience to reassess those early impressions. In this instance, the audience reconsiders the knee-jerk condemnation of Lady Grantham so as to sympathize with her plight as well. For all that she’s terribly wealthy and beautiful, she’s not expected to be much more than that. What’s sad is that she doesn’t expect to be, either; when she does, she’s put back in her place by her courtly – but no less paternalistic – husband.

Downton Abbey is, in effect, a thoughtful portrayal of the harsh reality of aristocratic women’s lives that lurked beneath the gilded exterior. They lacked autonomy and individual agency, were frequently treated as commodities, and the patriarchal, paternalistic society in which they moved colored their own self-worth. Men like Lord Grantham, as much a product of that society, nevertheless perpetuated their privilege, becoming active apologists for the very hierarchy that constrained their daughters. But beyond the beautiful clothes and the fabulous sets and the compelling acting is strong writing and purposeful manipulation of narrative structure. Julian Fellowes has rightly received glowing criticism for Downton Abbey’s plethora of witticisms and sharp one-liners, but the real achievement is in the narrative’s use of parallelisms to explore a single theme from different angles.

———-

[i] While the term “Edwardian” derives from the reign of Edward VII of England (1901-1910), historians sometimes extend the upper bound to include the sinking of the RMS Titanic (1912) or the start of European hostilities in the First World War (1914). For aristocratic families like the Crawley family at Downton Abbey, the rigid classism and social hierarchy (and its attendant mores) continued well into wartime.

[ii] Sharon Marcus’s excellent 2007 Between Women: Friendship, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian England is a wonderful, immensely readable but rigorously scholarly exploration of the full spectrum of female friendships, from the platonic to the intensely erotic. However, Marcus’s data is primarily drawn from sources written by historical women of the middle class, and some of their experiences (going to school, e.g.) would not have applied to any of the Crawley daughters. Lillian Faderman deals with the spectrum of friendships in the United States in roughly the same time in 2001’s To Believe in Women: What Lesbians Have Done for America, which includes chapters on upper-class women.

———-