|

| Winslet and DiCaprio star in Revolutionary Road |

Revolutionary Road

(2008) is almost a feminist film. It also just falls short of being something more than the hackneyed anti-suburbia types of film Sam Mendes revels in making.

A couple, who once fell in love over common artistic dreams, pulls off to the side of a highway to engage in verbal combat, sparked by the kitschy play the wife has just acted in, that threatens to turn physical. Each blames the other.

April Wheeler (

Kate Winslet) reflects on their life together throughout the next day. As she drags her metal trash cans to the curb to join the others aligned down both sides of their anything-but-revolutionary road, she recalls her real estate agent introducing her and her husband, Frank (

Leonardo DiCaprio), to their future home, the typically perfect white suburban house. Later, as she looks through old photographs, a second flashback recalls a conversation with Frank where she told him he was the most interesting man she had ever met.

As April reminisces about the hopes of the past, Frank woos a secretary at his cliché-ridden office job in a sales department. He gets her drunk, uses her as a shrink to confess that he has turned into his father despite his best intentions, and—as you already have guessed—sleeps with her. When he returns home past dusk, April meets him with smiles, an enthusiastic apology, and a birthday cake with thirty lit candles. Frank cries as his wife and two children—one girl, one boy—sing to him.

At this point I thought to myself, à la SNL’s Seth Meyers and alum Amy Poehler, “Really? Really? Do we really need to see another suburbia-is-the-ninth-circle-of-hell film? Really?” Hadn’t Mad Men already taken this trite formula to its farcical limits? The irony has lost its whip; there’s no need to tell us that life on Revolutionary Road is the conservative fast lane to Hades. We’ve been wise to the parable for some time: American beauty is anything but.

When I saw Frank washing away his infidelities in the shower, I puked a little in my mouth.

But then something unexpected happened. Instead of Kevin Spacey throwing a plate against a wall and toking up with his teenage daughter’s boyfriend, April lays bare the message of films like American Beauty. Road becomes meta-cinematic when she tells Frank:

Well, I happen to think this (suburban life) is unrealistic. I think it’s unrealistic for a man with a fine mind to go on working like a dog year after year at a job he can’t stand, coming home to a place he can’t stand, to a wife who’s equally unable to stand the same things. You want to know the worst part? Our whole existence here is based on this great premise that we’re somehow very special and superior to the whole thing, and you know what I’ve realized…? We’re not! We’re just like everyone else. Look at us! We’ve bought into the same ridiculous delusion. This idea that you have to resign from life and settle down the moment you have children. And we’ve been punishing each other for it.

With this piece of dialogue, a character within the film’s diegetic reality provides an accurate account of the predicament of the film’s starring couple…near the beginning of the film! Road replaces Beauty’s device of a dead male narrator who knows the foibles of his life only after it is over with a living, breathing, and INTELLIGENT female character who knows them and wants out before it’s too late. In a later scene, she tells one of their neighbors that she actually wants “in” to life, a nice reversal that equates suburban living with death, that favorite topic of anti-consumerist zombie films.

After some initial resistance, Frank agrees with April’s analysis and her diagnosis. They will move to Paris so that he may figure out what he wants to do with his life while she supports the family on secretary’s wages (thanks to France’s fairer treatment of women workers). Although such a plan seems anti-feminist on the surface, and one neighbor says as much upon hearing it, there is something liberating about it. Shots follow of April and Frank almost glowing with the prospect that they will soon be leaving the humdrum rhythms of Eisenhower America.

Of course, the best-laid plans of mice and couples often go awry, and the Wheelers fail to make it to Paris (I mused that their voyage would be cut short somewhere in the north Atlantic anyway). The Wheelers’ plans go awry when Frank comes up with a business slogan that impresses his higher-ups so much that they offer him a promotion. The irony is that Frank’s sudden show of corporate creativity only comes after he has convinced himself to leave. The mere thought of becoming a class traitor opens the wells of inspiration trapped inside him not a moment too late, which is so often the case, but a moment too early. The prospect of becoming a well-compensated company man leads him to waver on his early retirement. As if this were not enough, April discovers that she is pregnant with their third child. Although they convince each other that Paris is still in the cards, the odds seem stacked against them.

Here is where our co-heroes separate into their roles as protagonist and antagonist. I assert that Frank betrays April by buying into the “realist” narrative of his friends and colleagues, i.e. the American middle class. Notably, in the key scene where he dismisses Paris as a pipe dream, he responds to April’s proposal of an abortion like a Right-wing conservative.

April, a normal woman, a normal sane mother doesn’t buy herself a piece of rubber tubing to give herself an abortion so she can go live out some goddamned fantasy.

He reduces her to a scolded child, the idea of moving to Paris now considered a “childish dream.” Frank promptly resumes fucking his secretary like the mad man that he has become (and unconsciously always was and desired to be despite himself).

The ensuing fight between the Wheelers parallels the one that opens the film with one significant difference: although they both recognize that Truth has just spake, only April refuses to ignore it. She no longer loves Frank precisely because he is no longer the man she married, the man who wanted more from life than a cookie-cutter existence, and she reaffirms this fact. Frank cannot handle the Truth, and does his best to defend against it. He speaks for April, putting words in her mouth that she cannot express because she no longer loves him. April has not grown cold to him because of his unfaithfulness with another woman—April sleeps with another man, too—but his infidelity to himself.

The film should end with the two most disturbing scenes of all.

First, Frank awakens to find April playing Stepford wife. She pauses from cooking breakfast when he enters the kitchen and apologizes, just as she does earlier in the film with the birthday cake and party, except this time her words sound eerily scripted. Because Frank no longer cares about Truth and desires only to live in bad faith, he plays along, a bit surprised but also pleasantly amused. When he leaves, one gets the sense that he has bought into the male-centric American Dream. One knows that April hasn’t.

The second scene finds April crying in front of her mirror after Frank has left. She makes a fitful call where she threatens to break down at any moment to the babysitter watching her kids to ask if she can prolong her duties. The egg yolks that the camera focused on her scrambling in the prior scene retroactively become a foreshadowing moment, as she methodically carries out the abortion. When she descends the stairs, the camera focuses on her unsteady feet. Her face is pale. She goes to the window. The sun shines upon her and she lets out a small smile. Then a drip of blood falls to the carpet. The camera pans back to show a pool of blood expanding on the back of her skirt. She slowly moves out of the frame to make a phone call, “I think I need an ambulance…Yes…One one five Revolutionary Road…”

A perfectly disturbing end, right? No! Mendes cannot help but steal the show from his now ex-wife. Instead of ending with a shot of the blood on the carpet—the blotch in suburbia that betrays it a violent, life-draining lie—and April voicing the title of the film offscreen, Mendes includes a coda, a series of short scenes that a) turn the film anti-feminist and b) reinstate the generic codes of the cinematic anti-suburbia tract.

Instead of being left with a woman who may or may not be in critical condition, we learn that April dies, and her death acts as a sacrifice to return the men to normalcy. Frank moves to the city with his kids, thus finding some compromise between Paris and the American suburbs. The neighbor, who professed his unrequited love for April after she slept with him, becomes closer with his wife. We might brush these scenes against the grain to argue that they are the most feminist part of all because they show that female sacrifice undergirds the American Dream of the middle class, but they also inspire an unwarranted sympathy for Frank. The men are allowed to mourn almost as an act of contrition.

The final insult comes in the concluding scene where Mrs. Helen Givings (

Kathy Bates) tells her husband about how the new couple who has moved into the Wheelers’ house seems perfect for their abode. When the husband reminds her that she said much the same when the Wheelers moved in, she claims that she always knew that something was not right about the Wheelers, showing us that she, too, continues to live in bad faith by refusing to treat her Truth-telling son as the normal one (and not the folks she sells houses to). In my vote for the platitudinous scene of the decade, the husband is shown turning down the volume on his hearing aid.

Road should resolutely not be framed as a film about all suburbanites remaining deaf to the truth of their existence, as Mendes’s grandiloquent closing sequence suggests. The film is resolutely not about everyone’s bad faith. One woman, in the great tradition of Ibsen’s Nora Helmer, remains faithful to reality in an unreal setting and demonstrates her sanity despite her insane husband and unfaithful director.

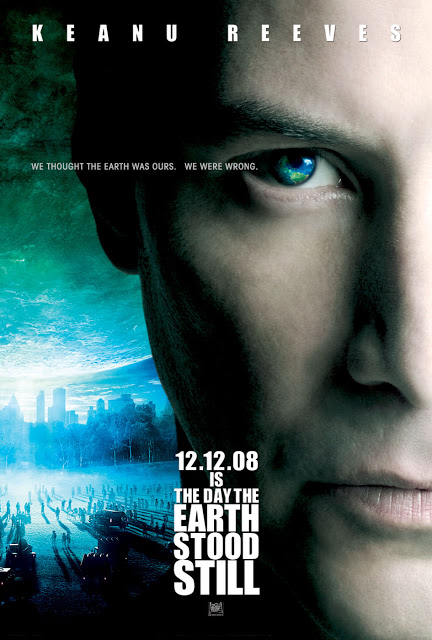

Kirk Boyle has previously contributed a Flick-Off of The Day the Earth Stood Still to Bitch Flicks.

The remake of The Day the Earth Stood Still‘s fraudulent feminism is exposed in how Klaatu (Reeves) is finally convinced to spare humanity in his bid to “save the Earth.” In a supposedly progressive way, the remake turns the traditional stay-at-home mother of the 1951 original (Patricia O’Neal) into a Princeton astrobiologist who is important enough to be put on a “vital list” of scientists and engineers who the U.S. government calls upon in the event of an imminent collision of “Object 07/493” with Manhattan. However, this liberal update is nothing but subterfuge.

The remake of The Day the Earth Stood Still‘s fraudulent feminism is exposed in how Klaatu (Reeves) is finally convinced to spare humanity in his bid to “save the Earth.” In a supposedly progressive way, the remake turns the traditional stay-at-home mother of the 1951 original (Patricia O’Neal) into a Princeton astrobiologist who is important enough to be put on a “vital list” of scientists and engineers who the U.S. government calls upon in the event of an imminent collision of “Object 07/493” with Manhattan. However, this liberal update is nothing but subterfuge. Only after witnessing a mother’s love does Klaatu feel that there is another side to humans (besides their unreasonable and destructive one), and curtail the attack of the killer nanobots. Unwittingly then, Benson changes Klaatu’s mind based on the advice Barnhardt gave her as they fled his house: “Change his mind not with reason, but with yourself.” In your standard anti-feminist fare, Barnhardt’s advice can only mean one of two things. Being a family-friendly film, the remake of Day passes on Benson’s seduction of Klaatu, deciding instead to confirm that she is a mother first and foremost, her position as scientist at a prestigious American university be damned.

Only after witnessing a mother’s love does Klaatu feel that there is another side to humans (besides their unreasonable and destructive one), and curtail the attack of the killer nanobots. Unwittingly then, Benson changes Klaatu’s mind based on the advice Barnhardt gave her as they fled his house: “Change his mind not with reason, but with yourself.” In your standard anti-feminist fare, Barnhardt’s advice can only mean one of two things. Being a family-friendly film, the remake of Day passes on Benson’s seduction of Klaatu, deciding instead to confirm that she is a mother first and foremost, her position as scientist at a prestigious American university be damned.