|

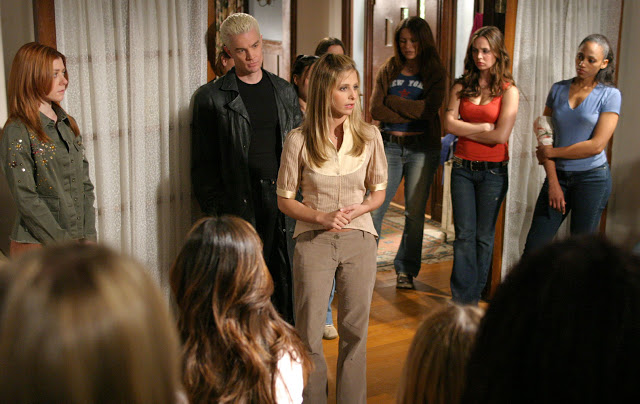

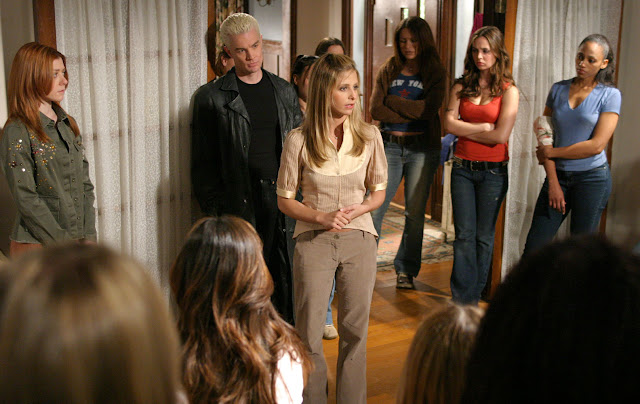

| Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Season 7 |

|

| Sarah Michelle Gellar as Buffy, looking pouty in a halter top |

Deborah Tannen explains the way in which women are denied a “default” state in the way they dress and portray themselves, stating that “if a woman’s clothing is tight or revealing (in other words, sexy), it sends a message… …If her clothes are not sexy, that too sends a message, lent meaning by the knowledge that they could have been” (622). If Buffy were portrayed as butch, she would just be a girl pretending to be a man. If she were portrayed as too vanilla in the way she dressed, spoke, and acted she would be less interesting; her plainness would also send a message to the viewer by making her more androgynous. Buffy may be saucy and sexy and contrived in the way she dresses, but that is part of what makes her character complex. She is a warrior but also, undeniably, a woman.

Thus it is interesting that the plot and dialogue of the show often does not reinforce Buffy’s feminine dress as a positive thing, but instead condemns her for it. In the episode “Bad Eggs” Buffy and her mother are shopping and Buffy wants a new outfit. Joyce says no, “it makes you look like a streetwalker”. Buffy pouts and replies, “but a thin streetwalker, right?” This scenario is sadly common. Buffy’s peers, her mentors, and authority figures criticize her appearance as if it were offensive, and Buffy deflects such comments with sarcasm instead of defending her right to determine her own physical appearance.

|

| Buffy working at Double Meat Palace |

As the show progresses and Buffy moves out of high school and into college and pursuing a career, she continues to encounter difficulty in her everyday life because of the dual identity slaying forces her to concoct. When her mother dies Buffy takes on the role of provider for her household. Buffy works a minimum wage job at Double Meat Palace to make ends meet as she is incapable of securing better employment. Buffy is eventually offered a position as a school counselor by the new principal in town, Robin Wood. In the episode “First Date” Principal Wood reveals that he knows that Buffy is the Slayer, and this is why he offered her a job. Buffy says, “so you didn’t hire me for my counseling skills?” and Principal Wood responds with a chuckle. Buffy may be powerful as the Slayer, but as a provider for her family and as an employee, her skills are portrayed as laughable.

Buffy’s necessary efforts to cloak some of her actions and engage in subterfuge to protect those unaware of vampires also constantly weaken her standing in society. Dramatic irony is often engaged as a plot device in BtVS, wherein Buffy is posed almost clownishly trying to hide the truth from an ignorant and often judgmental public. It is humorous as well as endearing to see how poorly Buffy lies, and Buffy’s lack of finesse outside of slaying does lend her character a great deal of humanity. Yet one must question why dramatic irony so often has Buffy playing the part of the bozo. Buffy is too often percieved of as flaky, inconsistent, or downright delusional. As one character says, a lot of people think Buffy “is some kind of high-functioning schizophrenic” (“Potential”). While Buffy may be possessing of super-human strength and a higher calling, it greatly impedes her ability to function as a normal member of society. She faces humiliation, prejudice, and conflict on a daily basis.

|

| Buffy and her mother Joyce |

As the series progresses Joyce becomes portrayed as less neglectful, but in the first few seasons especially there are serious questions to be asked about her role as a mother. She has a teenage daughter who sneaks out nightly, lies to her, skips classes and bucks authority and Joyce is largely incapable of informing her daughter’s actions. Much of the early dynamic between mother and daughter comes down to the fact that Joyce does not realize the reality of Buffy’s “dual identity as Slayer and Student… a greater failing than Lois Lane’s traditional inability to envision Clark Kent without his glasses” (Williams, 64). The fact that Joyce is kept ignorant and Buffy routinely shuns her mothering is not entirely Joyce’s fault. The Slayer cannot respect her mother’s authority because the Slayer’s role is more important than mother-daughter relations.

|

| Buffy and Angel |

Buffy’s later relationships may not be equally as tormented in terms of scale, but they do continue to revolve around themes of pain and conflict. This conflict is evident not only in romantic relationships, but in all her close relationships with men. Buffy even comes to blows with her mentor, Giles. While often their fighting is only in words, twice she resorts to hitting him. The first time occurs in the final episode of season one, “Prophecy Girl.” When Buffy realizes that Giles is going to sacrifice himself to save her life, she knocks him out in order to protect him. This action does lead to Buffy’s death by drowning, but she is resuscitated by her close friend Xander. The second time Buffy punches Giles echoes the first. In “Passion,” Giles is inflamed with rage after Angelus kills the woman Giles loves. Giles pursues Angelus in a suicidal rage. Again, Buffy resorts to blows in order to get through to Giles where words failed, to save his life. No matter how close the relationship, how deep the trust between two people, Buffy always seems to have to resort to her role as Slayer and her superhuman powers in order to make herself heard. This repeated theme has a serious connotation; Buffy as a girl is powerless. Her authority is intrinsically tied to her physical strength, which comes from her role as Slayer.

|

| From the episode “Hush” |

Often Buffy resorts to saying “I’m the Chosen One” when her authority is questioned; she is the Slayer, and that truth defines the way in which she acts and relates. Because of her power Buffy is forced to struggle in every area of her life. What message does this send to a young girl watching the program who is imagining being as powerful as Buffy? Rather than being an encouragement for girls to picture themselves as superheroes as boys so often do, BtVS sends the opposite message. Don’t pursue power, because that power will define your circumstances and those circumstances will define you. You will be forced to lie, to cheat, to sacrifice healthy relationships and to face constant conflict as a result of your independence.

It is unfortunately true that many shows that feature women as primary characters employ the same kind of storytelling. Xena: Warrior Princess, La Femme Nikita, The Closer, Alias, In Plain Sight, Saving Grace, Weeds and Battlestar Galactica all feature women as primary characters. All of the women in these shows have just a few things in common aside from their beauty: their intelligence and capability is challenged regularly; they face conflict in their private lives and homes; and they are punished for their physical and emotional strength. It is almost inevitable that any strong woman on TV would face the same treatment, especially those who play a traditionally masculine role. Starbuck from Battlestar Galactica, Xena, Nikita, Sidney Bristow of Alias, Mary Shannon of In Plain Sight and The Closer’s Brenda Lee Johnson all play traditionally masculine roles. All of those women face conflict and physical violence in almost every episode. Not only do they have to fight for respect, but their good works are seldom rewarded. Appreciation, respect, achievement, and victory are few and far between and must be won at high cost; home is not often a safe haven and interpersonal relationships are constantly disrupted. What is true for all of these female characters is especially true in the case of Buffy; she is a singular icon for female strength as well as for the punishment of feminine power.

|

| Buffy and Faith |

Male Superheroes do not receive the same treatment. Spiderman, Batman, and Superman may engage in conflict in their everyday lives as a result of their necessary deceptions, but it is certainly not to the measure which Buffy does; their familial ties are free from extreme stress. They all have close relationships with older figures who mentor them and preserve their familial ties (Aunt Mae, Alfred, and the Kents respectively). They have places they can go home to which are a respite from the pressures their dual identities create. Each of the male superheroes mentioned also receives a certain measure of success both in their chosen careers outside of crime fighting and their romantic lives. While Batman does not have any long term romantic relationships, he is a millionaire and dates often; he is rewarded for his power. Buffy is not afforded the kind of pleasures these male superheroes enjoy. It is because of that truth that Buffy’s story is far from empowering. Rather than showcasing a character who has achieved full agency as a woman and been rewarded for it, Buffy the Vampire Slayer instead chronicles one girl’s fight to be respected; a fight it sometimes seems she will never win.

The fact that women receive unequal treatment in today’s society is made wholly apparent in the fact that feminine strength is not showcased or rewarded in television media as masculine strength always has been. Until women are allowed to be feminine and strong without fear of their homes and lives being disrupted, or facing constant judgment and critical backlash, women will remain less than men. While Buffy the Vampire Slayer may have gone further than any show before it in creating a female character who was independent and powerful, the fact that her strength could not go unpunished leaves a gaping hole. Young women are still hungry for a role model who can navigate all of the complexities of modern womanhood successfully. Buffy’s final fight, the fight for respect, must not be left unwon. It’s time for a female superhero to get equal treatment: strength, intelligence, achievement, and reward.

http://www.rebelliouspixels.com/2009/buffy-vs-edward-twilight-remixed viewed 10/28/11

Early, Francis. “Staking Her Claim: Buffy the Vampire Slayer as Transgressive Woman Warrior.” Journal of Popular Culture 35.3 (2001): 11-17.

Jewett, Lorna. Sex and the Slayer: A Gender Studies Primer for the Buffy Fan. Middletown: Wesleyan, 2005. Print.

Magoulik, Mary. “Frustrating Female Heroism: Mixed Messages in Xena, Nikita, and Buffy.” Journal of Popular Culture 39.5 (2006): 729-55.

Tannen, Deborah. “There is No Unmarked Woman.” Signs of Life in the USA: Readings on Popular Culture for Writers. Ed. Sonia Maasik and Jack Solomon. 6th ed. Boston: Bedford St. Martins, 2009. 620-24. Print.

Whedon, Joss. Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Seasons 1-7. Television Program.

Williams, JP. Fighting the Forces: What’s at Stake in Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Ed. Wilcox, Rhonda, and David Lavery. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 2002. 61-68. Print.

———-