This is an anonymous review.

The radical notion that women like good movies

This is an anonymous review.

———-

It’s a matter of loose scriptural interpretation as to whether the Biblical Mary was a prostitute, but this version of her is. It’s never stated outright, but it is alluded to, surprisingly not in a disrespectful fashion. When Judas sneers at her that ‘It’s not that [he objects] to her profession, but she doesn’t fit in well, with what you (Jesus) teach and say,’ Jesus immediately (and angrily, for JCS’s Jesus has something of a temper) slaps him down as a hypocrite. ‘When your slate is clean, then you may throw stones/ If your slate is not, then leave her alone!’ It’s notable, and unfortunate, that Mary doesn’t speak up for herself in this scene, instead allowing Jesus to come to her defence, but her profession–which it’s implied she still practises–is never shamed by the larger narrative.

Further, though she may be in love with Jesus, it’s not a one-dimensional, love-interest kind of emotion. Indeed, the show makes plain that she has no idea what to do with it. In her song aptly titled ‘I Don’t Know How to Love Him,’ she’s shown as someone used to being in control of a situation, in control of her own emotions. Again, her profession as a sex worker is referenced when she rationalises to herself that she’s had lots of men, she knows how to deal with men, Jesus ought merely be one more. But for some reason, he’s not, and that scares her. As the song goes on, she even says, ‘Yet, if he said he loved me/ I’d be lost, I’d be frightened/ I couldn’t cope/ Just couldn’t cope.’

Refreshingly, though we see the positive aspects of her love in her behaviour toward Jesus, it’s also portrayed as what love often is; an overwhelming emotion. Mary is an independent, rational, controlled woman with an inner life who is, frankly, freaked out and doesn’t know how to deal with her own reactions.

|

| Mary (Yvonne Elliman) washes Jesus’s (Ted Neeley) feet in the 1973 film |

Later in the show, Mary is the one who confronts Peter about his denial of Jesus, sure where he is scared, and in the film, they have a duet, ‘Could We Start Again Please?,’ in which they lament that things have gone too far, and beg an absent Jesus to let them start over and do it again. Although in the scene with Peter, Mary is the strong one, she’s still fallible and unsure, and while in previous scenes, she’s seemed separate from the Apostles, here she is Peter’s comrade.

So, for a show and film with only one real female character, not bad. Not amazing, but certainly not as bad as it could be. However, where JCS really becomes interesting is in other respects.

Though this is intended to examine the show through a feminist lens, intersectionality is key, and so mention must be given to race. Though the practise of colourblind casting has been open to some debate as to whether or not it’s actually a good thing (allowing, for instance, such un-self-aware gaffes as all-white productions of The Wiz with the argument that they’re being colourblind, they’re being progressive), in the 1973 film of JCS, it’s practised about as truly as I have ever seen. The ensemble of disciples is about as diverse racially as they are among gender lines, and of what one might term the ‘main’ cast, Judas and Simon Zealotes are played by black men, Mary Magdalene a woman of mixed Irish, Chinese, and Japanese descent, and the actor who plays Herod is Jewish. Somewhat ironically, come to that. Actors of colour are not relegated to unimportant side characters; they can be anyone.

|

| Simon Zealotes (Larry Marshall) and a group of disciples encourage Jesus to a militant revolution against the Romans |

|

|

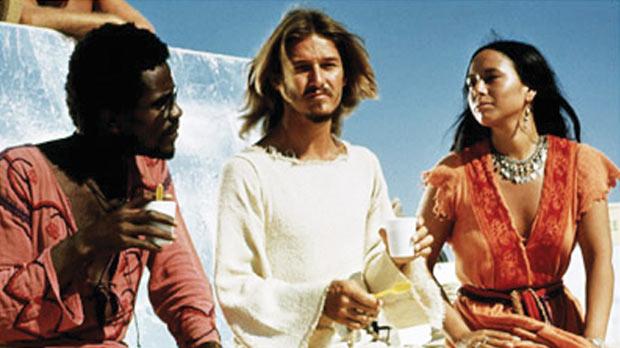

Carl Anderson (Judas), Ted Neeley, and Yvonne Elliman on set

|

One such reading is the relationship between Jesus and Judas. In the show, Judas is the main character, flawed but sympathetic, a tragic tool of destiny. He is written explicitly as a foil to Mary Magdalene; they both love Jesus, but Judas is challenging, afraid, untrusting of Jesus’s ability to handle what he’s started; he even gets a reprise of her song, ‘I Don’t Know How to Love Him,’ as if the comparison wasn’t already clear. JCS makes it clear that Judas does love Jesus. Whether or not the role is crosscast, his scorn for Mary Magdalene is often played as the result of his jealousy over her. Some people might say that a crosscast show makes a strained romantic or sexual relationship between Jesus and Judas more obvious, but I would argue that a queer reading of a non-crosscast show is just as valid, and indeed it is occasionally played that way. Productions have been known to make Judas’s betraying kiss less a brotherly brush of the cheek, and more a desperate, angry, farewell kiss on the mouth.

When Jesus is crosscast, that also has the potential to change the relationship between himself and Mary Magdalene, as the only two women in a crowd of men. It also, perhaps more significantly, makes the prophet and leader of a cultural and religious movement female. It is all too common for works of fiction, as well as real-life movements, to revolve around men, and changing such a male leader to a female one is making a statement about gender and power, not to mention the trope of ‘the chosen one,’ a character type almost exclusively male. Thanks to ingrained cultural conventions about gender, it also changes the dynamic of things like the reasons behind the Sanhedrin’s decision to arrest Jesus, or the scene in which Pilate has him stripped and flogged. If Jesus is a woman rather than a man, such scenes will almost inevitably read differently.

The answer to my question, then, would be: both. Some things, mainly the interpersonal relationships, have precedent in the text, and crosscasting largely affects only how queer they are or aren’t, whereas larger societal issues which may crop up genuinely are not there in the original text.

Ultimately, Jesus Christ Superstar is interesting and feminist not necessarily because of what the text of the show itself presents, which may change from production to production, but because of the convention it carries which allows for queering of the text, of changing the gender of characters, of being free with the race of those cast. It would be difficult to imagine that happening with a show like The Secret Garden or Les Miserables.

———-

Barrett Vann is an English and Linguistics student at the University of Minnesota. An unabashed geek, she’s into cosplay, literary analysis, high fantasy, and queer theory. After she graduates in December, she hopes to tackle grad school for playwrighting or screenwriting, and become one of those starving artist types.

|

| Cinderella (1950) |

James: “The man said marvelous things would happen!”Glowworm: “Did you say marvelous pigs in satin?”

———-

Singin’ In The Rain (dir. Stanley Donan & Gene Kelly)

While the genre can whisk you away to foreign lands, and domestic bliss, it is also historically problematic when it comes it its representations of women, and gender in general. Though the men are singing and dancing, they are always men’s men, expressing their gender through ruggedness and emotional unavailability. The women are often window dressing, and pawns in the plot, rather than autonomous people who have actual emotions and ambitions. Singin’ In The Rain suffers from some of the same issues that many musicals have with their treatment of genders, but it does have a surprisingly progressive character as well.

We first meet Kathy when Don Lockwood (Gene Kelly) jumps in to her car to escape a throng of overzealous fans. With Kathy driving herself we instantly associate her with independence. And unlike the pursing fans, Kathy can act logically and contain herself.

The thing that I find unique about Kathy’s character is that she is so balanced. She is never a caricature. She is able to keep up with Don and his buddy Cosmo (Donald O’Connor), but she never veers into becoming “one of the guys” by sacrificing her femininity just to match them in comedic timing. She also dances and sings along with them, but never as a partner who is put there to make Don look better. And it seems no matter what else is thrown at her, she remains herself. Being so self aware and content is not always shown for characters in musicals. Frequently the women are shown as aggressive career women who sacrifice themselves for their careers (Majorie Reynolds in Holiday Inn) or women who are put there just to be romanced by the main character. Kathy is strong enough to not only know who she is, but also can be true to herself and pursue both her personal life and her career.

To read more of Ana’s writings, including her snarktastic literary deconstructions, visit her website at www.AnaMardoll.com.

|

| The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993) |

|

| Shock |

|

| Sally |

———-

Jessica Critcher loves to write about feminism and gender issues, and she is a regular contributor to Gender Focus. While she loves living in Boston, she often misses Honolulu, where she earned her bachelor’s degree in English (and forgot that there was such a thing as snow).

This is a guest review by Clint Waters.

Roughly ten years ago, the Broadway musical Chicago was adapted for the silver screen by Bill Condon and directed by Rob Marshall. This film is oh-so appropriate for Women and Gender in Musicals Week because it explores the darker side of an era when First-Wave Feminists had recently won the right to vote and were continually fighting for equality. However, instead of picket lines and hunger strikes, the women of Chicago manipulate sexuality and violence to gain the upper-hand over their male counterparts and for a myriad of other less-than-pure intentions.

Roxie Hart, our lady protagonist played by Renee Zellweger,

An unforgettable number, “The Cell Block Tango,” occurs during Roxie’s first of many nights in Jail. As the lights go out and she sobs herself to sleep, the cells come alive with individual sounds that form a Stomp-esque intro to the song where several inmates detail what brought them there. Each of them is in for the murder of a lover or husband.

Here, we have an interesting blend of shades and hues labeled “femme fatale.” Most are revealed to have killed for seemingly silly reasons and others for being scorned by adulterers. What makes the number unforgettable is their sheer crassness toward their victims, yet they still cling to their pleas of not guilty: “I didn’t do it, but if I done it, how could you tell me that I was wrong?” This scene also has some very striking visuals and imaginative uses for red cloth representing blood/death:

I don’t mean to say that I dislike this movie. In fact, you will never hear me say that. I LOVE this movie. Although it may not be the deepest of films, it knows what it is and does it well. Aesthetically speaking, it is a gorgeous film with gorgeous women and takes a lot of strides to make everything look and feel Vaudevillian. As I mentioned earlier, the songs take place in Roxie’s mind, so the creative directors spared no expense on blending stage effects with surrealism. (For example, the audience, while played by real people, sits motionless like wax figures because after all, the show is about Roxie. In another scene the members of the media are literally represented as the puppets that they are.)

———-

In 1821, Oregon Territory, Adam Pontipee (the impossibly rugged Howard Keel) is looking to fetch himself a wife—not for the purposes of high-falutin’ romance, family, and lifelong happiness, no. “I’d like best a widow woman that ain’t afraid to work,” he says, at the general store, where he’d just as quickly pick up a mate as he would 25 pounds of chewing tobacco. “There’s seven of us men, me and my six brothers. Place is like a pigsty, and the food tastes worse….” Adam is out for marriage in the purest economical sense: in this new territory, there are ten men for every woman, and so Adam’s priority is availability, not compatibility.

“Bless Yo’ Beautiful Hide,” he booms, and it’s not until he sees Millie (Jane Powell, strong of axe and soft of heart) that he knows he can go out and buy with gusto. She makes great stew, so that’s half the battle, and she is used to tending men in a boarding house, so he considers her the perfect bride.

He offers marriage, she accepts (as she’s fallen for him on first sight), and off they go in his wagon back to his cabin in the mountains, where she meets his six red-bearded, bullish brothers. Millie bristles at caring for her brother-in-laws without some control, and so she withholds a hot breakfast and newly washed clothes until they promise to shave and settle down like gentleman. It seems that what this house has longed for is not an extra hand in the washroom, but a gentle and firm guide to proper etiquette.

What Millie discovers, as she gets to know these boys, is that they long to go out and snatch up girls of their own—which they do, in spectacular fashion, at the town’s barn raising. The brothers Pontipee, all in primary colors, demonstrate through dazzling choreography how dashing and desirable they can be, and sweep the girls off their feet. Just watch how leapfrogging, arm wrestling, log-rolling, and balletic machismo pays off. (This is the most spectacular sequence of the movie, and it’s impossible to watch without a slaphappy grin. Jacques d’Amboise and a very young Russ Tamblyn steal the show as Ephraim and Gideon, defying gravity with every move.)

If you watch the actual movie, as I did, as a European expat teaching in a Hong Kong international school and grappling with cross-cultural questions on a daily basis (you try teaching A Bridge To Terabithia to a class of city-dwelling Chinese boys) — not so much. Mulan has always been a problematic text for me because it tries so hard to be culturally sensitive and gender-aware that it positively creaks, and those creaks can be heard by the least-savvy member of the target audience. Its sins are not the sins of historical omission of, say, Snow White or Sleeping Beauty, but are all the more egregious because they come from a place of awareness. Mulan is an attempt to fix something that was perceived to be, if not wrong, unbalanced. This clumsy attempt to wedge The Ballad of Mulan into the rigid, alien form of a Disney narrative (which, among other things, demands musical numbers, a comic sidekick and a Prince Charming to come home with at the end) doesn’t fix anything, and only serves to remind us what is broken about our global culture. The road to hell is, as ever, paved with good intentions, particularly when it heads from the West to the East.

So, ever mindful of the accusations of racial insensitivity that had been tossed at Aladdin and Pocahontas, and anxious to get it right this time, Disney sent key artists on the movie to China, for a three-week tour of Chinese history and culture. Three weeks! You can totally “do China” in three weeks. This was enough to give them all the visual reference points they needed, and the whistle-stop, touristic nature of their impressions is very much in evidence on the screen. Every Chinese guided tour cliché is tossed into the scenery hotchpotch, from limestone mountains to the Great Wall to the Forbidden City. This isn’t so bad – other Disney movies are set in a vague Mittel-Europe of mountains, forests and lakes – but the loving attention paid to trotting out the visual truisms of courtyard complexes, brush calligraphy, cherry blossoms et al is just window-dressing. Mulan does look like China, but only if you’re leafing through your holiday photos back in your Florida office.

There’s nothing particularly Chinese about Mulan herself, who is so brutally meant to be not-Disney Princess and not-Caucasian it hurts to look at her for long. Poor little Other. She’s shown wearing Japanese make up, and has a facial structure more suggestive of Vietnamese than Chinese (Disney really was embracing post-colonialism). For half the movie, she also has to be not-female. The lack of detail on a 2-D Disney face meant the animators had to design her as able to switch between genders via her hair – and something subtle going on with her eyebrows. The resulting face evokes, more than anything, a pre-op kathoey who hasn’t yet taken advantage of Thailand’s booming plastic surgery clinics in order to make zer gender-reassignment complete.

Oh, Mulan. She’s meant to be non-offensive, and she ends up being not-anything. Despite claims to the contrary, she’s not a feminist hero. She has to dress as a boy to achieve selfhood, and refuses political influence in order to return to the domestic constraints of her father and husband-to-be. The movie itself doesn’t even pass the Bechdel test, if you consider that the only topic the other female characters discuss is Mulan’s marriageability – a hypothetical relationship with a man. The final defeat of the antagonist is achieved by the male Mushu riding on a phallic firecracker, as Mulan flails helplessly at his feet. Positive female role model? Case closed.

Mulan wouldn’t seem like such a frustrating, failed attempt to push gender and cultural boundaries if it had been followed up by other stories of empowered female warrior heroes. A Disney version of Joan of Arc or Boudicca could have been a blast. Unfortunately, since 1998, it’s been pretty much princess as usual. On the bright side, Disney achieved some of their other goals with Mulan. Hong Kong Disneyland (itself the subject of accusations of crass cultural insensitivity) has been doing brisk business since 2005, thanks to a US$2.9billion investment by Hong Kong taxpayers (of which I was one). The majority of tourists are from mainland China. They come to marvel at Western icons like Mickey, and an all-American Main Street that’s a replica of the one in Anaheim. Thanks to the ubiquitous presence of Mulan images, they stick around. It feels a tiny bit more like they might have a stake in the happiest place on earth.

This is a guest review by Jessica Freeman-Slade.

The 1968 movie is legendary, almost impossible to remake due to Streisand’s unforgettable turn (recreating her role from the 1964 stage musical), and with music by Jule Styne and lyrics by Bob Merrill. It’s based on the true story of 1920s entertainer Fanny Brice, one of the major attractions in the golden age of Florenz Ziegfeld’s Follies. Fanny knows she’s a star, but is constantly told that her unconventional looks will keep her off the stage (or as her neighbor puts it, “If a girl’s incidentals/are no bigger than two lentils/then to me it doesn’t spell success.”) But Fanny stands out, because she’s hilariously funny and has a golden voice, and so fame, like anyone who watches the movie, finds her irresistible. What the movie has at its core, is a message about female self-confidence, about self-reliance, about how the world reacts to strong women, and how, ultimately it’s all about chutzpah. Which Fanny (and Streisand) has in spades.

Streisand had only appeared in one Broadway show before then, a small but memorable part in I Can Get It for You Wholesale, and she was far from the only candidate to play Fanny. When Jule Styne consulted Steven Sondheim about the development of the show, Sondheim had major qualms about potentially casting a marquee star like Mary Martin. “I don’t want to do the life of Fanny Brice with Mary Martin. She’s not Jewish,” he said. “You need someone ethnic for the part.” And Streisand was ethnic, especially when put up against a bevy of chorus girls that looked like they’d stepped straight out of Beach Blanket Bingo. The other contenders before her included Anne Bancroft, Martin, and Carol Burnett, but Streisand took the ugly duckling premise and turned it on its head every time she sang. (Fanny’s first line to a skeptical producer says it all: “Suppose all you ever had for breakfast was onion rolls. Then one day, in walks… a bagel! You’d say, ‘Ugh, what’s that?’ Until you tried it! That’s my problem—I’m a bagel on a plate full of onion rolls.”) And she stood out among the other Broadway stars at the time, in the same way Fanny did in her day.

Yes, I know. You have to believe that this girl…

…is considered unattractive, uncastable, and undesirable.

The real Brice had big gummy features–a clown’s face. And though Streisand looks gorgeous in every shot, even in Fanny’s pre-fame days (check out those amazing nails), she doesn’t lose her undeniably ethnic look. She stands out, especially when surrounded by all the Aryan thin-nosed beauties of the Ziegfeld follies. And so the premise of Funny Girl, of almost every joke, rests on whether you believe that Fanny, despite her face, earns every drop of success because of her extraordinary talent. Each joke has the same structure: someone throws a derogatory comment Fanny’s way. Fanny volleys, with wit and acid and intelligence. The movie provides a model to every girl out there (no matter how attractive she is) about how to deal with a world that doubts you because of your appearance, because of your difference. When everyone’s a critic, especially in the entertainment industry, and you know you’re something special, they will have to accept you as you are, and fall in love with you for what you bring to the performance. Just watch Fanny’s first performance for a theater, and how she bends the audience to her will:

Then the joke changes—how could a guy as perfect and beautiful as Arnstein fall for a gummy-faced girl like Fanny? Because he knows what the rest of the world doesn’t—that she has a spark, she stands out, and that’s a sign she’s going to be a star. But the movie, as it traces Fanny’s rise to stardom, constantly returns to the presumably unassailable fact that she can’t hold Nick, or anything, in place simply by being female and beautiful. And so the movie becomes a commentary on what an unconventional woman does to keep herself successful in a world that doesn’t immediately recognize her talent.

Fanny, blessedly, has little time for people who insist she behave conventionally. Even when she lands the dream job, as a featured player among the glittering chorines of Ziegfeld’s follies, she balks at behaving like any other starlet. When Ziegfeld (Walter Pidgeon) puts her in the star spot in the closing number, she says, “I can’t Fanny: I can’t sing words like: “I am the beautiful reflection of my love’s affection.” I mean… Well, it’s embarrassing… If I come out opening night…telling the audience how beautiful I am, I’ll be back at [my first job] before the curtain comes down.” When he refuses to do so, Fanny concedes, but finds her own special twist for the number:

Even when Fanny hooks Nick, and even after she gets to sing a ditty about how great it is to be “Sadie, Sadie,” married lady, the story continues to treat Fanny as a liability. When Nick finally starts showing his shortcomings as a card shark, he is too insecure and prideful to ask Fanny to bail him out. He is thrown into prison, and Fanny gets the news just as she’s heading out of the theater for the night. “You still love him, Miss Brice?” the reporters shout. “The name’s Arnstein,” she replies defiantly. This is a woman who refuses to let her critics define her—even if it means putting the joke on her.

What ultimately carries Fanny, and Funny Girl, as one of the greatest musical comedies ever (and makes Fanny one of the best characters, male or female, ever written for Broadway) is that her weapon is always her strength, her self-reliance, that aforementioned chutzpah. Fanny truly believes that she can do or accomplish anything, including saving her own doomed marriage, if someone just gives her the chance. When she and Nick decide to separate after his release from prison, she is utterly heartbroken. But even in that moment, she pulls herself up and delivers a superb performance, looking more beautiful and elegant than ever. And that’s where the message of Funny Girl really sings out: NOTHING is as radiant as self-confidence.

———-

Jessica Freeman-Slade is a writer who has written reviews for The Rumpus, The Millions, The TK Review, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and Specter Magazine, among others. She works at Random House as a cookbook editor, and lives in Morningside Heights.