It’s a matter of loose scriptural interpretation as to whether the Biblical Mary was a prostitute, but this version of her is. It’s never stated outright, but it is alluded to, surprisingly not in a disrespectful fashion. When Judas sneers at her that ‘It’s not that [he objects] to her profession, but she doesn’t fit in well, with what you (Jesus) teach and say,’ Jesus immediately (and angrily, for JCS’s Jesus has something of a temper) slaps him down as a hypocrite. ‘When your slate is clean, then you may throw stones/ If your slate is not, then leave her alone!’ It’s notable, and unfortunate, that Mary doesn’t speak up for herself in this scene, instead allowing Jesus to come to her defence, but her profession–which it’s implied she still practises–is never shamed by the larger narrative.

Further, though she may be in love with Jesus, it’s not a one-dimensional, love-interest kind of emotion. Indeed, the show makes plain that she has no idea what to do with it. In her song aptly titled ‘I Don’t Know How to Love Him,’ she’s shown as someone used to being in control of a situation, in control of her own emotions. Again, her profession as a sex worker is referenced when she rationalises to herself that she’s had lots of men, she knows how to deal with men, Jesus ought merely be one more. But for some reason, he’s not, and that scares her. As the song goes on, she even says, ‘Yet, if he said he loved me/ I’d be lost, I’d be frightened/ I couldn’t cope/ Just couldn’t cope.’

Refreshingly, though we see the positive aspects of her love in her behaviour toward Jesus, it’s also portrayed as what love often is; an overwhelming emotion. Mary is an independent, rational, controlled woman with an inner life who is, frankly, freaked out and doesn’t know how to deal with her own reactions.

|

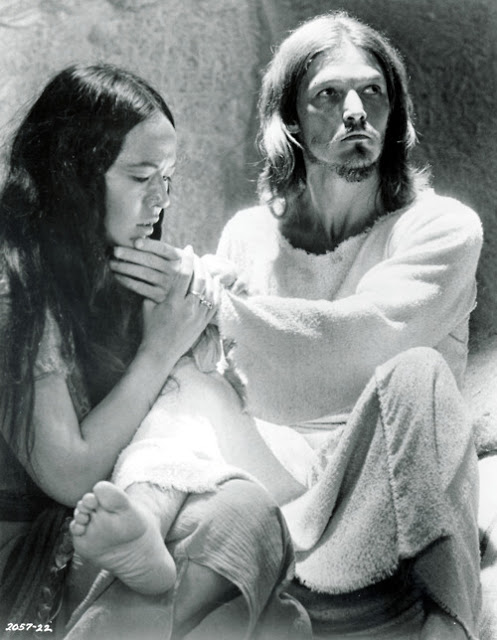

| Mary (Yvonne Elliman) washes Jesus’s (Ted Neeley) feet in the 1973 film |

Later in the show, Mary is the one who confronts Peter about his denial of Jesus, sure where he is scared, and in the film, they have a duet, ‘Could We Start Again Please?,’ in which they lament that things have gone too far, and beg an absent Jesus to let them start over and do it again. Although in the scene with Peter, Mary is the strong one, she’s still fallible and unsure, and while in previous scenes, she’s seemed separate from the Apostles, here she is Peter’s comrade.

So, for a show and film with only one real female character, not bad. Not amazing, but certainly not as bad as it could be. However, where JCS really becomes interesting is in other respects.

Though this is intended to examine the show through a feminist lens, intersectionality is key, and so mention must be given to race. Though the practise of colourblind casting has been open to some debate as to whether or not it’s actually a good thing (allowing, for instance, such un-self-aware gaffes as all-white productions of The Wiz with the argument that they’re being colourblind, they’re being progressive), in the 1973 film of JCS, it’s practised about as truly as I have ever seen. The ensemble of disciples is about as diverse racially as they are among gender lines, and of what one might term the ‘main’ cast, Judas and Simon Zealotes are played by black men, Mary Magdalene a woman of mixed Irish, Chinese, and Japanese descent, and the actor who plays Herod is Jewish. Somewhat ironically, come to that. Actors of colour are not relegated to unimportant side characters; they can be anyone.

|

| Simon Zealotes (Larry Marshall) and a group of disciples encourage Jesus to a militant revolution against the Romans |

|

|

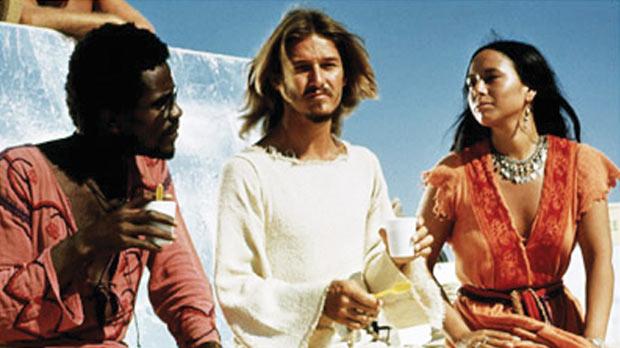

Carl Anderson (Judas), Ted Neeley, and Yvonne Elliman on set

|

One such reading is the relationship between Jesus and Judas. In the show, Judas is the main character, flawed but sympathetic, a tragic tool of destiny. He is written explicitly as a foil to Mary Magdalene; they both love Jesus, but Judas is challenging, afraid, untrusting of Jesus’s ability to handle what he’s started; he even gets a reprise of her song, ‘I Don’t Know How to Love Him,’ as if the comparison wasn’t already clear. JCS makes it clear that Judas does love Jesus. Whether or not the role is crosscast, his scorn for Mary Magdalene is often played as the result of his jealousy over her. Some people might say that a crosscast show makes a strained romantic or sexual relationship between Jesus and Judas more obvious, but I would argue that a queer reading of a non-crosscast show is just as valid, and indeed it is occasionally played that way. Productions have been known to make Judas’s betraying kiss less a brotherly brush of the cheek, and more a desperate, angry, farewell kiss on the mouth.

When Jesus is crosscast, that also has the potential to change the relationship between himself and Mary Magdalene, as the only two women in a crowd of men. It also, perhaps more significantly, makes the prophet and leader of a cultural and religious movement female. It is all too common for works of fiction, as well as real-life movements, to revolve around men, and changing such a male leader to a female one is making a statement about gender and power, not to mention the trope of ‘the chosen one,’ a character type almost exclusively male. Thanks to ingrained cultural conventions about gender, it also changes the dynamic of things like the reasons behind the Sanhedrin’s decision to arrest Jesus, or the scene in which Pilate has him stripped and flogged. If Jesus is a woman rather than a man, such scenes will almost inevitably read differently.

The answer to my question, then, would be: both. Some things, mainly the interpersonal relationships, have precedent in the text, and crosscasting largely affects only how queer they are or aren’t, whereas larger societal issues which may crop up genuinely are not there in the original text.

Ultimately, Jesus Christ Superstar is interesting and feminist not necessarily because of what the text of the show itself presents, which may change from production to production, but because of the convention it carries which allows for queering of the text, of changing the gender of characters, of being free with the race of those cast. It would be difficult to imagine that happening with a show like The Secret Garden or Les Miserables.

———-

Barrett Vann is an English and Linguistics student at the University of Minnesota. An unabashed geek, she’s into cosplay, literary analysis, high fantasy, and queer theory. After she graduates in December, she hopes to tackle grad school for playwrighting or screenwriting, and become one of those starving artist types.