This guest post by Karina Wilson appears as part of our theme week on The Brat Pack.

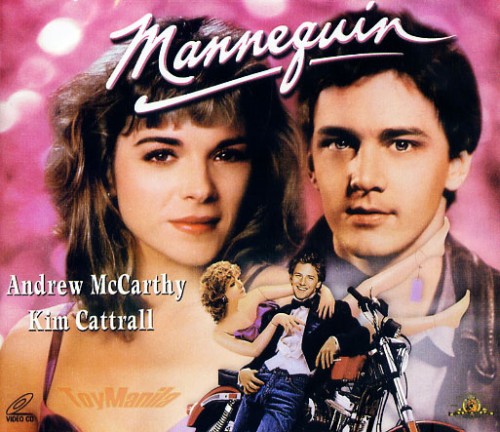

By any regular standards, even the 1980s, Mannequin is a TERRIBLE movie. It never should have been green lit, let alone hit wide release. It’s often lumped in with other Brat Pack pics, thanks to the presence of Andrew McCarthy and James Spader, but it really should be categorized separately, as a romcom gone wrong. Showroom dummies that come to life after hours should be the stuff of horror movies, or episodes of Doctor Who, not fluffy fantasies starring a nearly naked Kim Cattrall. John Hughes wouldn’t have touched this material with a ten-foot pole.

It’s hard to believe the filmmakers ever thought audiences would fall for the outrageous plot. An Ancient Egyptian princess, Emmy (Kim Cattrall), escapes arranged marriage to a camel dung salesman by disappearing in a puff of smoke and reincarnating as a showroom dummy in 1987 Philadelphia, where she finds true love with the career-challenged Jonathan (Andrew McCarthy) inside a glittering retail palace (Wanamaker’s, now Macy’s Center City). She exploits the well-documented Philadelphian obsession with classy department store window displays to turn Jonathan’s life around, defeat the bad guys, and [SPOILER ALERT] get married (in a climactic window display!) and live happily ever after.

Critics, understandably, hated it. Roger Ebert thought it was, quite literally, DOA (“Mannequin is dead. The wake lasts 1 1/2 hours, and then we can leave the theater”). Janet Maslin in the New York Times lamented the lack of substance (“In place of a real story, there is just the spectacle of stock characters being put through their paces to fill up the time”) and lousy performances (“It’s never a disappointment when the mannequin, which comes to life only intermittently, turns back into wood”). Leonard Maltin called it “absolute rock-bottom fare. Dispiriting to anyone who remembers what movie comedy ought to be.” Yet it was a hit – grossing more than $42 million off a $6 million budget – and was nominated for an Academy Award – for Starship’s theme song, “Nothing’s Gonna Stop Us Now.”

I willingly confess to loving Mannequin. It’s so wrong, it’s absolutely right. It’s a big, tatty rescue pooch who plants her paws on your chest and gives you a slobbery kiss of a movie: certain people, dog people, Mannequin people, can’t help but be charmed. Even now, watching it as a hard-bitten 40-something, it invokes my inner impressionable teen.

I adore the unromantic hero, Jonathan Switcher, because he manages to be simultaneously weird and endearing. There’s something a bit off kilter from the top: when we first meet him, he’s salivating over a naked clothes dummy. He exudes every which way of warning signal, from the pronounced doll fetish to the Frankenstein complex to the social ineptitude. When the dummy-making gig doesn’t work out, he is hired and quickly fired from a succession of menial occupations, which consequently causes him to be dumped by his improbably put-together girlfriend, Roxie (Carole Davis). Poor Jonathan would drown instantly if forced to dive into the perilous depths of the 2014 dating pool. However, this was the 1980s, when you could splash about in the shallow end and still qualify as Kim Cattrall’s dream date. On the plus side, Jonathan rides a Harley, lives in a sweet studio apartment (obviously comes from money, yay 1980s!), and he’s Andrew McCarthy. Andrew fucking McCarthy. Be still, my perpetual adolescent heart.

For those of you who don’t recall, Andrew McCarthy was the Beta Male of the Brat Pack. He wasn’t as beautiful as Rob Lowe, or as badass as Judd Nelson, or as peppy as Robert Downey Jr., but you’d take him over Anthony Michael Hall or Jon Cryer any day. He had a burning blue stare, a voice that dropped to a creaky growl when – as often happened – his character was wracked with emotion, and a lift to his chin suggesting a stubborn streak a mile wide. He was cool enough to pop his collar and run with the in-crowd, but he was also sensitive enough to be an individual, even (shock!) an artist, and follow his dream. He was the Nice Guy before the term became so ridiculously devalued. He was the boy who might, quite unexpectedly, offer to walk you home after prom turned to tears, and then turn misery and humiliation into the most enchanted evening of your life through the power of his goofy grin and kind eyes. I loved him then and I love him still.

He’s wasted in Mannequin. He does his best with the material, and manages to make Jonathan geeky and adorable, a whisper away from quietly insane: in lesser hands, the guy would be plain creepy. McCarthy makes it halfway believable that Emmy, who has had her pick of hot dates (Christopher Columbus!) throughout history, might finally settle for the lowest status employee in the store. And Cattrall keeps up Emmy’s end of the deal, regarding Jonathan as a feline would a toy stuffed with catnip – with unadulterated delight. She bats him between her paws, chews on him gently, and, when the montage is done, curls up beside him and goes to sleep. Girl clearly likes to dominate, and there’s a coy whiff of BDSM about some of their dress-up-and-play. What else are they going to do with those tennis racquets other than spank each other’s ass?

In a cute subversion of romcom norms, then, Emmy is the Alpha Female who picks out the Nice Beta Male early on in the narrative and seduces him with a plastic smile. She has been dating for millennia. When she sees it, she knows exactly what she wants – and it ain’t the traditional alpha hero. Jonathan and Emmy are perfect for one another from the moment they lay eyes on one another. There’s no need for a makeover montage. This is due to bad storytelling rather than feminist innovation, but it’s so refreshingly unusual, it works. She’s content to dazzle, he’s content to be awed – and when required, he saves her life. We should all aspire to such a Mr. Right.

The writers, Michael Gottlieb and Edward Rugoff, manage to throw a few obstacles in the happy couple’s way (the course of true love never did run smooth) in the form of manic supporting characters. Forget three-dimensional, thinking, feeling, human beings – crass stereotypes abound. There’s flamboyant, gay, black, promiscuous Hollywood (Meshach Taylor), the set designer who takes Jonathan under his sateen wing. Estelle Getty pops up as the store’s owner, Claire Timkin. G.W. Bailey reprises his Police Academy shtick as Felix, the bumbling security guard – Cattrall was a fellow alumni, best known for her sex kitten turns in Porky’s and Police Academy at this point, so he must have felt at home. And there’s the villainous Richards, James Spader abandoning his usual sexy-husky bad-boy turn in favor of playing a rival storeowner with cartoonish slicked-back hair and outsize spectacles. None of it makes much sense. But somehow Jonathan and Emmy win and Richards and Roxie lose and the finale is all “Nothing’s Gonna Stop Us Now” most triumphant good.

That’s all, folks. Mannequin is fun, but wafer-thin. Although considered a cult classic, it has zero cultural significance, especially when compared to the canon Brat Pack hits that defined a generation. It’s a vapid Technicolor fantasy that, by being so poorly conceived and written, accidentally manages to subvert all the other Pygmalion stories. Flimsy as she is, Emmy is the romantic heroine who doesn’t have to be reshaped or reinvent herself in order to deserve her adoring swain. All she needs is for us to believe she’s real.

Karina Wilson is a British writer and story consultant based in Los Angeles. She writes a regular column on horror fiction at Litreactor and can also be found at Horror Film History.