|

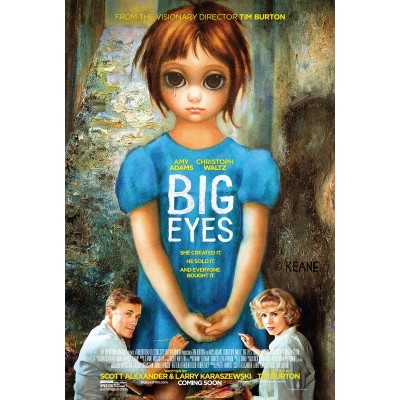

| Lady Van Tassel (Miranda Richardson) |

As a director, Tim Burton specializes in eerie, off-kilter films that frequently skirt the edge of light horror with a distinctive aesthetic; 1999’s Sleepy Hollow is one of his earliest forays into the genre. Starring Johnny Depp, Christina Ricci, and Miranda Richardson, the lavishly-produced film is an adaptation of the short story by Washington Irving, and tells the re-imagined tale of Ichabod Crane and his efforts to solve a series of murders in the small New York town of Sleepy Hollow. While Sleepy Hollow effectively creates the kind of visually rich, engrossing film viewers expect from Burton, it is also full of curious decisions that cast its female characters in frequently (unflattering) lights. This review, a (transatlantic) dialogue between friends, aims to track the ways in which these narrative and directorial decisions affect the portrayal of Sleepy Hollow’s women, making problematic characters of Lady Van Tassel (Miranda Richardson) and her step-daughter, Katrina Van Tassel (Christina Ricci).

[BB]: I think the first angle we should consider is the woeful lack of strong women who aren’t insane, though Lady Van Tassel is likely better described as angry. She’s probably insane with the need for revenge, but everything she does is very cool, calculated, and intelligent. But first of all, what do we define as a ‘strong woman’? I suppose for me it’s a woman capable of acting in her own interests and making choices for herself. And, in the words of a friend, “she does what she needs to do.”

[AC]: I think that’s a good place to start. And a strong character doesn’t have to be a nice one, but I think that he or she does have to be more than a narrative device. And in this film, I think there’s only one female character who really fits that bill.

[BB]: It’s interesting that Lady Van Tassel – the wicked stepmother – is actually new to the Burton film, whose script rewrites the story.

[AC]: Lady Van Tassel is probably the first casualty of the new script. She’s not the character who’s mentioned only obliquely in the story, Van Tassel’s ‘noble wife’ who’s happily occupied with keeping her home; this character exists in the film, but she’s already dead. Lady Van Tassel is the second wife, stepmother to the sweetly angelic Katrina, Ichabod’s love interest. Obviously Sleepy Hollow is significantly different from Irving’s short story, but I can’t help but wonder at the decision to write the script they way they did. Increasing Katrina’s role is understandable – and problematic, as I’m sure we’ll discuss – but the reinterpretation of Lady Van Tassel is troubling, too. Rewriting her as the stepmotherly villain certainly emphasizes the fairy-tale aspect of the story, and that’s something that frequently fascinates Tim Burton, but Irving’s story works well as a fairy-tale, too, with the Brom-Katrina-Ichabod love triangle. I wonder why they chose to rewrite Lady Van Tassel as they did, particularly given that there’s a ready-made villain in Brom. Why make that decision, and further, why send Lady Van Tassel so far over the cusp of madness?

[BB]: This is interesting actually. It’s been so long since I read the short story I forgot all about Brom’s role as the ‘villain,’ but in Burton’s adaptation Brom, though he begins initially as something of an antagonist, actually redeems himself when he fights off the Hessian and is, sadly, killed. In contrast, Lady Van Tassel reveals her backstory, reveals how she has suffered at the hands of the Van Garretts and the Van Tassels – suffering which perhaps explains her need for vengeance, yet she remains utterly unsympathetic and is portrayed in an increasingly unflattering light. Her strength is negated by her evilness, and she becomes increasingly unhinged.

[AC]: I think you’re right in that her evilness seems to counteract her strength. She might be the only female character working with a degree of individual agency, but because she’s working toward nefarious ends, she’s not someone to be emulated. And then by pairing her opposite Katrina, we’re left with the idea that women must either be power-hungry and crazed or meek and lovesick.

[BB]: Although does the intended genre of Burton’s adaptation effect the characterisation of his female characters?

[AC]: Irving’s short story is an effective fairy tale – it’s written in fairytale language (Katrina’s described in idealized terms, her father is noble and good, etc.) and follows the basic structure of a fairytale (there’s a hardscrabble hero fighting against the establishment man for the hand of the pretty daughter of the town’s leading citizen; some past event has created the conditions for the present trouble to occur, etc.). Unfortunately, in Irving’s story, the hero doesn’t actually succeed – but endings are easy enough to alter. Burton made more far-reaching changes than that with his characterization of a new Lady Van Tassel.

[BB]: But why change the villain if Burton already had the bones of a fairytale? If he wanted it to fit into the horror genre, sure, throw in a real undead horseman, but keep the villain. Although is romance a good enough motive? I suppose we can’t ignore the plot either – for a movie requires more action than does a short story, particularly one nuanced like Irving’s – but even that explanation falls short.

[AC]: It’s actually as if Burton took the situation and the concept of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and went from there. It’s really not much of an adaptation at all; it just borrows the characters and places and reimagines them in a completely different context; there’s so very much that’s different about it that I don’t know whether we ought to be comparing the two. At the very least, Burton’s Lady Van Tassel has some agency; she has her moments of clarity and moments of madness, and ultimately, the former are most certainly at the service of the latter. When she’s not raging, she’s certainly the strongest female character of the film. But she’s beset by violent tendencies, however much a product of childhood traumas; she’ll never be a role model for the children.

[BB]: Strong women don’t necessarily need to be role models, though. I certainly wouldn’t want my children to raise the headless horseman from the dead to exact revenge for previous injustices, but I can admire Lady Van Tassel’s forbearance – she and her sister are left alone, as children, in the Western Woods, yet she ensures their survival and raises herself to a position of some importance in the village. Of course her motives are questionable but does that diminish her strength?

|

| Katrina Van Tassel (Christina Ricci) |

[AC]: Given the way that the other lead female character is portrayed, I have the impression that it’s a deliberate editorial decision to make the one strong female character into the antithesis of a role model. The audience is meant to identify – or if not identify, at least feel for – sweet Katrina Van Tassel, who does all she can to save the man she loves. But Katrina isn’t nearly as well-rounded a character as Lady Van Tassel. She’s more of a generic type of filler than anything else; to compensate for the lack of development of Katrina’s character, it’s as if they wanted to ensure that Lady Van Tassel would be so offensive and so off-putting that they made her into something bordering on a monstrous caricature. Even the costuming is meant to emphasize this: Katrina is almost always dressed in pale colors, frequently in white, whereas Lady Van Tassel is dressed in darker colors.

[BB]: Let’s talk about Katrina. I just don’t think there’s much substance to her. She’s very needy. She goes from the protection of one man (her father) straight to another (Ichabod). On the other hand, I suppose she does go into the Western Woods when most of the men won’t.

[AC]: But that might just make her reckless, not strong.

[BB]: I’m not sure she’s being reckless, but she’s not doing it wholly out of bravery, but out of love. But does that lessen her courage?

[AC]: Well, you’re right: she still does it, after all, but I’m ambivalent about Katrina in the same way that I am about Bess in The Highwayman. I don’t think doing something out of love lessens the courage or the bravery of the act, but I also don’t think that an instance of bravery is necessarily synonymous with “strong female character.”

[BB]: No, I agree: one foray into the Western Woods isn’t enough to change my opinion of Katrina’s character. Instead, I would have preferred to see Katrina volunteering her services as a “sidekick” for lack of a better word – though that term is problematic in itself – much earlier in the film, before she has a chance to fall for Ichabod.

[AC]: I agree: but there isn’t a moment where Katrina doesn’t fall for Ichabod, until Ichabod suspects her father of controlling the Horseman. Their romance is established in the first few minutes of the film, when Katrina kisses Ichabod in a game of blind man’s bluff. Katrina does assist Ichabod, but she’s acting for him, not herself, though that isn’t to say that she’s ego-centric. It’s simply that she enters the Woods to support him when no one else will go; she doesn’t go because she wants to solve the mystery. I suppose my opinion of Katrina plays into my problem with making the girl sacrifice everything for love. Consider Bess, after all: she kills herself to warn the highwayman that the soldiers are lying in wait at her father’s inn. She’s willing to sacrifice herself to save him – that’s love, perhaps, but that’s not self-worth. I wonder if we’d be having this discussion if things ended differently for Katrina: would we raise the issue of her courage at all if she died? I think if we said we wouldn’t consider her running into the Western Woods to be brave had she died (rather that it would have been the natural consequence of a foolish, lovesick, reckless action), it would be because there hadn’t been that foundation to her character. That’s a legitimate issue with the way the character is written. So my question, perhaps better phrased, would be: does the film give us enough in the way of backstory, of character development, to perceive Katrina’s running into the Western Woods as an example of strong, individual agency?

[BB]: Oh, not at all. We learn precious little about her. The only characters we actually get real backstory for are Lady Van Tassel and Ichabod Crane. Katrina isn’t considered important enough for a backstory.

[AC]: What’s interesting is that her role was greatly expanded for the film; Katrina is much more of a bit player in the short story. In this case, she really is a kind of light-horror manic pixie dream girl. She’s a young female character whose part in the story has been greatly expanded in the film adaptation solely to facilitate Ichabod’s success. She’s important only relative to Ichabod: as his love interest, as his assistant. The writing deliberately excludes the potential for a strong female character (who isn’t of questionable sanity) in favor of pumping up its male lead.

[BB]: To be fair, she’s certainly not a strong character in the short story. The screenwriter and director have a choice when adapting something: they don’t necessarily need to stick to the source material when it comes to characterisation.

[AC]: That’s what makes Katrina’s expanded role so disappointing to me: they could have done more with her, as you say, and instead, they took a minor character, turned her into a lead, but didn’t give her additional substance.

[BB]: To be honest, that seems to be the case in many Burton films: it’s supposed to be about the male lead.

[AC]: Now that you say that, I’m reminded of Dark Shadows, which has lots of female characters but basically two leads: Elizabeth and Angelique.

[BB]: Yes, I think Elizabeth could have been stronger. We had snippets of strength, but she falls flat next to the characterization of Barnabas Collins.

[AC]: Elizabeth plays second fiddle to Barnabas, ceding control of the estate and the business. She’s basically waiting in Collinswood to be rescued, and we’re meant to be grateful that her rescuer is as dashing and mysterious as Barnabas. The question becomes, how will he save the family business and not why didn’t she do so? After all, that’s what Angelique does: she builds Angel Bay; it’s not her fault that her success comes at the expense of the Collins family business. If she could do it, why can’t Elizabeth?

[BB]: Now that you mention Angelique, I find her character rather problematic also. Angelique could have been quite a strong character, but she falls short. Everything she does, we come to find out, was done out of love for Barnabas, and in the end, she ‘died’ of love for him. Never mind that she’s built up this modern empire and has a powerful position in the community. None of that matters next to Barnabas.

[AC]: We’re actually meant to despise her character for those reasons, because it’s her business that’s ruined the Collins family business, and her high profile in the town that’s limiting their own.

[BB]: She’s villainized for her strength, and I think the same can be said for Lady Van Tassel. You see it as her character descends further into madness: we understand her childhood trauma and follow her evil plotting until she’s been reduced to a caricature of a villain, shouting increasingly ridiculous lines like “Watch your head!” and “Still alive?”

[AC]: I wonder if that’s the natural consequence of making Lady Van Tassel into a strong character? Does the fact that they’ve rewritten her into a larger role – and accordingly given her power – necessitate turning her into a typical fairy-tale villain, so that she must she become the Evil Queen/Evil Stepmother/etc.? That’s how fairy tales conceive of their villainous ladies, after all, and the female characters who don’t fit that stereotype usually aren’t what we would call “strong.” In this sense, is Burton actually emphasizing this aspect of the fairy-tale genre?

[BB]: I suppose so, though fairytales do not necessarily need a female villain. As you said before, the short story itself could be described as a fairytale and did not have a female villain. Rather than creating an entirely original role (even if I think the character of Lady Van Tassel only adds to my personal enjoyment of the film) why not utilise the ready made villain the short story offers? I wonder if it’s not because the choice of a female villain gives Burton and his artistic staff more flexibility in terms of the visuals: let’s talk about costuming. What does that add to our understanding of Burton’s motivations?

[AC]: If you look at Angelique’s costuming, she’s objectified like Lady Van Tassel. As Lady Van Tassel descends further and further into madness her costumes become more ridiculous; her cleavage is more and more on display; she takes down her own hair. These are clearly purposeful choices, and they’re effective ones, too. Most strikingly, her costumes, with few exceptions, put her breasts prominently on display.

[BB]: That’s an understatement. I don’t think there’s a moment Lady Van Tassel’s breasts aren’t on display and that’s quite interesting in itself. Katrina is billed as the female lead, and as she’s the object of affection for the romantic lead I would have expected to see more of her than the middle-aged Lady of the Manor. I can’t bring myself to believe that this isn’t deliberate, so that the costuming deliberately emphasises Katrina’s purity and goodness in comparison with Lady Van Tassel’s already irredeemably corrupted soul. On that note, as well as rather prominently displaying her body, Lady Van Tassel also uses sex to get what she wants – she keeps Magistrate Phillips in line with midnight trysts in the Western Woods – and is villainized for that too.

|

| Lady Van Tassel’s descent into madness, emphasized by her hairstyling and dress |

[AC]: As I said before, the color of Katrina’s clothes emphasize her status as the good witch of the family. Yes, she is – and incidentally, so is Angelique. Would you say that this is emblematic of a larger pattern in Burton’s films?

[BB]: Perhaps. But is he really going for a strong narrative? Or just a pretty film?

[AC]: Fair point. I think in many cases, the aesthetic is of incredible importance to him. His films have a definable look; he deals in the visual, first and foremost. But on the other hand, he can’t expect us to wave away criticism of the narrative – or not look into it too deeply – when, as in the costuming, say, the aesthetics actually echo the problems of the scripts.

[BB]: Of course; you can’t sacrifice substance just because it looks very pretty.

[AC]: I think Burton would probably say that the aesthetic of the film is of equal importance, because he’s as much of a visual storyteller as a verbal one.

[BB]: I do think that Burton is motivated by his desire for an attractive, genre appropriate film, rather than challenging female stereotypes and promoting female strength within his films. And that’s fine by me: I don’t think Burton is pretending Sleepy Hollow is anything but an incredibly pretty film.

———-

Bexy Bennett is a history student at King’s College London. Her (research) interests include transatlantic marriages between 1870 and 1914 and the relationship between servant/employer in Victorian and Edwardian England. She also has a keen interest in Australian history, and when she’s not studying she’s fangirling Mrs Danvers and drinking copious amounts of tea. You can find her on twitter @madamdictator.

Amanda Civitello is a Chicago-based freelance writer and Northwestern grad with an interest in arts and literary criticism. She has most recently written on Jacques Derrida and feminist philosopher Sarah Kofman for The Ellipses Project and has contributed reviews of Downton Abbey and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind to Bitch Flicks

. You can find her online at amandacivitello.com.