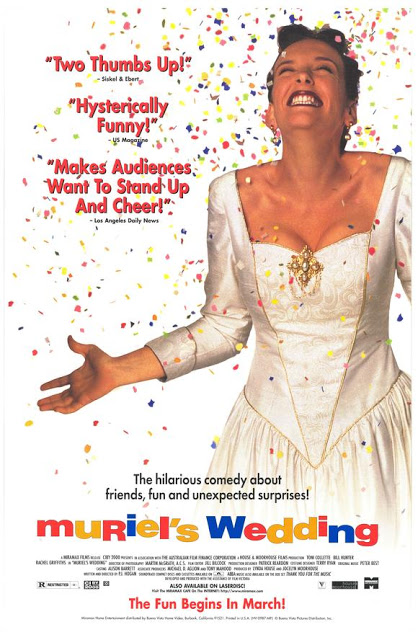

The first time I saw Muriel’s Wedding, I went in expecting a Cinderella-esque romantic comedy about an awkward girl who transforms her life into one filled with success and romance. I was definitely ready to indulge in your standard ‘feel-good chick-flick.’ Two hours later, as I sat surrounded by a pile of tissues, having cried myself into a near comatose state, I realized that Muriel’s Wedding has one of the most deceptive posters ever.

The film starts at a wedding in the small Australian town of Porpoise Spit, where we are introduced to the film’s titular character, Muriel Heslop. The wedding day is filled with disasters for Muriel: She catches the bridal bouquet and is forced to give it to another woman; she discovers the groom and the bride’s best friend fooling around; and is accused of having stolen from a local store.

As Muriel is carted home by the police, we see a glimpse of her highly dysfunctional family life. Ruled over by their tyrannical politician father, the Heslop children are a collection of deadbeats and slackers. Muriel herself hasn’t worked in over two years, and continues to live out of her childhood bedroom. Their mother, Betty Heslop, is little more than a slave to the family’s whims, and has visibly checked out from her surroundings. Attempts to communicate with her take several tries, and her brief moments of pleasure are quickly squashed by her husband.

It soon becomes apparent that Muriel’s thieving is a common occurrence, as her father handles the police with relative ease, and is able to use his power to keep them from pressing charges. Muriel waits calmly in her room as he dances the familiar steps with the officers, only to be verbally attacked in front of her father’s business guests and family later that evening. Bill Heslop seems to have no trouble belittling his family publicly, calling each of them “useless” repeatedly before being interrupted by a “surprise” visit from his obvious mistress, (an event which occurs with alarming frequency.) The night only gets worse from there, as Muriel’s so called “friends” accidentally let slip that they were going on holiday without her. The situation snowballs, leading the four women to kick Muriel out of their group.

Under the guise of travelling for a job, Muriel follows the women to an island resort, still believing that she can convince them to take her back. There, Muriel runs into an old high school classmate, Rhonda. The two women spend the rest of the vacation together, and instantly become best friends. They dance to ABBA together, they move to Sydney together, and generally bring out the best in one another. Rhonda’s support and independence also help Muriel to break out of her shell and begin living life the way she has always dreamt it. Eventually, Muriel finds herself a job at a local video store, and is asked out by a shy customer. The two date briefly, and share one of the movie’s most unforgettable and hilarious scenes when they attempt to be intimate.

Unfortunately, the good times don’t last, and Muriel is dealt a series of harsh blows by reality. With Rhonda becoming paralyzed from a spinal tumor, and Muriel’s lies becoming exposed; Muriel’s dream life begins to unravel. In a desperate attempt to break her father’s hold on her and live her dream, Muriel agrees to marry an attractive South African athlete. The man, David Van Arkle, let’s his displeasure about the arrangement be well-known, but needs to marry in order to stay in the country. When their wedding day rolls around, David looks as if he’s going to be sick. Muriel is completely oblivious however, basking in the attention of the media and her former friends. So oblivious in fact, that Muriel completely leaves out her mother from the event. In a tear-inducing scene, Betty rushes to the wedding, glowing with pride, only to have Muriel walk right past her without noticing. Still holding her daughter’s wedding gift in hand, Betty can’t help but cry as the guests dissipate.

When Muriel arrives at her new home with her husband, the fantasy of the day fades, and David accuses her of being nothing more than a gold digger. He divides their lives in half, and sends Muriel to her room alone. Soon after, Muriel receives a call from her sister, informing her that their mother has died.

Rushing home for the funeral, the house is just as Muriel left it. Her siblings laze about the living room; their father calculating the effect of Betty’s death on his political campaign. One sister is truly upset though, and confides in Muriel that their mother died of an overdose of sleeping pills. Their father, fearing his image, hid all evidence of her suicide. It is then that Muriel discovers what occurred on her wedding day, and realizes how her lies had helped to destroy her mother.

David appears at the funeral, sympathetic to his wife’s pain. The two return home together and make love, only to have Muriel ask for a divorce in the morning. She admits that her life has become a lie, and that she never felt anything for David. He agrees, and the two part ways.

In the last scene of the film, Muriel returns to Porpoise Spit, where Rhonda has had to return to her mother’s care. Forced to endure the pity of her former enemies, Muriel’s apology is readily accepted, and the two escape back to Sydney together.

And though I may have gone in expecting Hollywood’s attempt at pigeon-holing Muriel’s Wedding as a rom-com, I still came out loving this film. It takes a brutally honest look at the ripple effect of emotional abuse throughout a family, and delivers all too real characters who you can’t help but become emotionally invested in. The women of the film in particular are wonderfully refreshing, led by the endearing Toni Collette. Her portrayal of Muriel is definitely an unforgettable one. Whether it be her natural, un- glamourized looks and figure, or her very human flaws, the character of Muriel feels intensely genuine. While Hollywood films often use clumsiness to disguise the unachievable-ness of its movie’s heroines, Muriel’s Wedding instead prefers to tell it like it is. Everyone’s choices lead to consequences, and the end of the film does not mean the end to their problems.

The Muriel we are presented with in the beginning of the film; a girl who is desperate for attention, mildly delusional, and devoid of self-respect; is almost meant to be underestimated. We are shown all her worst qualities in a matter of minutes, and lead to pity her circumstances. As the movie progresses and Muriel grows, she becomes more outgoing and self-sufficient, but her lies remain. When her father threatens her new lifestyle, Muriel initially responds by entreating further into her fantasies, only to have them come crashing down upon her. Once she confesses to David and finally begins to admit the truth, we come to realize just how much Muriel has grown. Now confident and self-aware, she is able to stand up to her father’s demands and fearlessly return to her old life.

The friendship between Muriel and Rhonda is one filled with ups and downs, but is still the most genuine relationship in the film. While Rhonda becomes repeatedly frustrated with Muriel’s lies, the two are ultimately accepting of one another, and deeply loyal. Rhonda herself is a free spirit who speaks her mind and does as she pleases. She gleefully stands up to Muriel’s friends, and later takes home two men at once. Even when she receives her diagnosis, Rhonda remains determined to be independent. While she is eventually forced back into her mother’s home, she doesn’t stay long; returning to Sydney with Muriel in a matter of weeks. Rhonda’s fearless embrace of her life and choices, compared with Muriel’s sweetness and hope, make the two a perfectly balanced pair.

However, the women Muriel call her friends are the more stereotypical “mean girls.” They are portrayed as vapid, conniving, promiscuous, and cruel. Even after repeated physical and verbal attacks, Muriel invites them to be bridesmaids at her wedding, if only to show off her success at finding a famous and handsome husband. But even by the film’s end, their stunted growth remains, leaving them as flattened villains.

Muriel’s mother, Betty, is the true reason that this film breaks my heart. Having witnessed a near identical situation in my grandmother’s life, the inclusion of her storyline is especially meaningful. At no point does the director show her any kindness; from her husband’s blatant affair, her children’s indolence, being accused of shoplifting, to Muriel’s own snubbing of her; Betty endured a terrible existence. Spoiled by the happy endings of American cinema, I had internally begged for a magical fix to her suffering; some kind of ‘hallelujah’ moment where we were assured everything would be alright.

When Betty eventually suffers an emotional break down and commits suicide, it is only Muriel and her sister who show any concern whatsoever. The other siblings are completely unaffected; the youngest girl gossiping on the phone with her friends the morning after her mother’s death. Bill Heslop, who selfishly tries to cover up his wife’s cause of death and his part in causing it, uses the sympathy of the press to further his career.

Betty’s story is one that never allows the viewer any release. Instead, it speaks of a harsh reality where there is no sudden intervention of fate, moments of enlightenment, or redeemable villains. We never get to see Bill Heslop punished for his cruelty, or Betty rewarded for her love for her children. And it is because of such that I think Betty Heslop is a fantastic female character. While she may not be the empowered woman who takes back her life from an abusive husband, she is a real woman, with real emotions, and a painfully real situation.

In the end, whether you’re interested in a good laugh, cry, or simply want to watch wonderful film, I highly recommend Muriel’s Wedding to you. Its realistic portrayal of women and their emotional experiences make it a gem in anyone’s collection.

———-

Libby White is a self-proclaimed cinephile and Volunteer Firefighter who currently works as an Armed Guard for Nissan’s headquarters in Tennessee.