|

| Arabic movie poster for Where Do We Go Now? |

—

The radical notion that women like good movies

|

| Arabic movie poster for Where Do We Go Now? |

—

A French family with two daughters, 10-year-old Laure and 6-year-old Jeanne, moves to a new neighborhood during the summer holidays. With her Jean Seberg haircut and tomboy ways, Laure is immediately mistaken for a boy by the local kids and passes herself off as Michael. Filmmaker Céline Sciamma brings a light and charming touch to this drama of childhood gender confusion. Zoe Heran as Laure/Michael and Malonn Levanna as Jeanne are nothing less than brilliant. This is a relationship movie: relationships between children, and the even more complicated one between one’s heart and body.

Incendies: Lebanon Is Scorched, Burned and Blistered

|

| A cinematic moment. The image comes first and the explanation comes much much later. |

|

| Violence and pain become sources of empathy and identification for the audience. |

|

| The now classic diasporic subject returning to the ‘homeland’ and looking. |

|

| The protagonist is played by Lubna Azabal, a Moroccan actress who is a contender to be the next generation Hiam Abbas. Hiam Abbas is the Arab world’s Meryl Streep. |

Just after the death of her newly-born sister, Chanda, 12 years old, learns of a rumor that spreads like wildfire through her small, dust-ridden village near Johannesburg. It destroys her family and forces her mother to flee. Sensing that the gossip stems from prejudice and superstition, Chanda leaves home and school in search of her mother and the truth. Life, Above All is an emotional and universal drama about a young girl (stunningly performed by first-time-actress Khomotso Manyaka) who fights the fear and shame that have poisoned her community … Directed by South African filmmaker Oliver Schmitz (Mapantsula), it is based on the international award winning novel Chanda’s Secrets by Allan Stratton.

By Liz Braun:

Life, Above All is an historical snapshot of the AIDS crisis in Africa and an indictment of sorts of the government bungling that allowed the epidemic to overwhelm South Africa. The culprits (ignorance, poverty, big pharma, religious and political leaders, etc.) are not so much the focus; the point of this quiet, heartbreaking drama is all those children left to cope, especially the orphans.

By Nora Lee Mandel:

Rather than focusing on the usual corrective lessons on the transmission and treatment of HIV/AIDS, the family’s struggles play out within systems of traditional care and limited modern medical facilities that are strained to the breaking point. Chanda rails against the stoic comforts of religion and receives only discouraging advice at an overcrowded clinic. Her illiterate and exhausted mother falls prey to the greed of a charlatan doctor, a demon exorcism, and horrific neglect by her revengeful sister, who has not forgiven Lillian for her flouting of tribal marriage traditions for the sake of love.

By Manohla Dargis:

Chanda’s silence is unnerving, as is the absence of tears, and while her calm conveys a preternatural strength of character it also suggests a lifetime of pain. No child, you think, should have to pick out her baby sister’s coffin. But she does, taking in the horror of the funeral home and its metal table without flinching and then pushing forward, still dry eyed, still determined, taking on life with an appealing (and enviable) toughness and grace that make this difficult story not just bearable but also absorbing. As the weight of the world bears down on her slender frame, she becomes the movie’s moral compass and its authentic wonder: the child who is forced to be an adult yet remains childlike enough to feel real.

By Mary Corliss:

Two years ago, a drama with a seemingly forbidding subject — an illiterate teenage girl, pregnant with her father’s child and hellishly abused by her drug-addicted mother — won over critics, audiences and the members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. The film was Precious. Now comes Life, Above All, which deals with the tragedy of AIDS in South Africa, as seen by a 12-year-old girl named Chanda. At the end of its world premiere at last year’s Cannes Film Festival, critics cheered like schoolkids, giving it a 10-minute standing ovation.

By Alison Willmore:

… when its focus narrows onto Manyaka and her mother (Lerato Mvelase), their deep mutual affection and the terrifying sacrifices they’re ready to make because of it, the film sings, becoming a moving tribute to love holding fast against suffering. The ending, which offers a hint of relief, is unfiltered, frankly unbelievable melodrama, but something grimmer and more measured would be intolerable after everything that comes before.

I want to make it clear up front that I don’t know enough about Japanese culture and Welsh culture to comment on how culture has impacted this transition. In fact, I haven’t even seen the movie undubbed. Accordingly, this review will compare a book that was published in English, to a version of the film that was released in English though Disney, and which was marketed to an American audience.

| This romantic imagining of Howl says it all (source: Dreamhuntress on flickr) |

|

|

| Enemy of the State: Heroine Lisbeth Salander Fights Back in The Girl Who Kicked The Hornet’s Nest |

This is a cross post from Opinioness of the World.

|

| Michael Nyqvist stars as Mikael Blomkvist |

In the U.S., the first book entitled The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

In the U.S., the first book entitled The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

|

| Annika Gianini (played by Annika Hallin) with Lisbeth Salandar (Noomi Rapace) |

She does not complain and she doesn’t accept being a victim. Almost everybody has treated her so badly and has done horrible things to her but she doesn’t accept it and won’t become the victim they have tried to force her to be. She wants to live and will never give up. I find that so liberating. Her battle is for a better life and to be free and I think everybody experiences that at some point in their life. They say OK, I’m not going to take this anymore. This is the point of no return. I’m going to stand up and say no. I’m going to be true to myself and even if you don’t like me that’s fine. I don’t want to play the game of the charming nice sexy girl anymore, I’m me. I think everybody can relate to that.

|

|

| Good Girl Gone Bad: Noomi Rapace as Lisbeth Salander Burns Up the Screen in The Girl Who Played with Fire |

|

| Rebel with a Cause: A Feminist Heroine Emerges in film The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo |

This is a cross post from Opinioness of the World.

The story revolves around the disappearance of Harriet Vanger, the niece of a wealthy business tycoon, who vanished without a trace 40 years earlier. Harriet’s uncle has been tortured by her absence all these years. Journalist Mikael Blomkvist, who’s been convicted of libel, and Lisbeth Salander, an introverted punk who’s a brilliant researcher and hacker, seek to solve the baffling mystery. The book is a riveting twisting thriller with numerous suspects.

Blomkvist is an interesting character. A charming and passionate journalist championing for the truth, he vacillates between cynicism and naïveté. Dejected after his conviction, he yearns to clear his name. He also frequently bed hops yet has enormous respect for women, often befriending them. While acclaimed Swedish actor Michael Nyqvist gives a valiant effort, he does not imbue the character with enough charisma.

But the sole reason to go see the movie (and read the book too) is for Lisbeth Salander. Noomi Rapace, who won a Guldbagge Award (the Swedish Oscars) for her portrayal, plays her perfectly. She stepped into the role by training for 7 months through Thai boxing and kickboxing (in the books Lisbeth boxes too) as well as piercing her eyebrow and nose, emulating Lisbeth’s punk look. A nuanced performance, Rapace plays the tattooed warrior with the right blend of sullen introvert, keen intellect and fierce survivor instincts. Salander is a ferocious feminist, crusading for women’s empowerment. Facing a tortured and troubled past, Salander is resourceful and resilient, avenging injustices following her own moral compass. An adept actor, Rapace conveys emotions through her eyes, never needing to utter a word. Yet she can also invoke Salander’s visceral rage when warranted.

Also, if you’re like me and reading each book before you see the film and you haven’t read the second book yet, be prepared for spoilers as there are scenes NOT in the first book that are taken from the second book and integrated into the film, such as Lisbeth’s flashbacks and the topic of her conversation with her mother.

In the book, Larsson makes social commentaries on fiscal corporate corruption, ethics in journalism, and the role of upbringing on criminal behavior. Larsson also provides an interesting commentary on gender roles with his two protagonists. Despite Blomkvist’s social nature and Salander’s private behavior, they both stubbornly follow their own moral code. Both also possess overt sexualities. Yet society views Blomkvist as socially acceptable and perceives Salander as an outcast. These themes are absent from the movie adaptation.

In the book, Larsson makes social commentaries on fiscal corporate corruption, ethics in journalism, and the role of upbringing on criminal behavior. Larsson also provides an interesting commentary on gender roles with his two protagonists. Despite Blomkvist’s social nature and Salander’s private behavior, they both stubbornly follow their own moral code. Both also possess overt sexualities. Yet society views Blomkvist as socially acceptable and perceives Salander as an outcast. These themes are absent from the movie adaptation.

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo has received an exorbitant amount of attention for Larsson’s controversial central theme of violence against women. It’s true that both the book and film portray graphic violence. The movie does not shy away from the uncomfortable subject matter. In the book, women fall prey to being assaulted, murdered, and violently raped. A pivotal rape scene disturbs and haunts the viewer. But sexual assault is a reality women face, albeit an ugly truth that we as a society may not want to see. Yet Larsson in the book and Oplev in the film never made me feel as if women were victimized. On the contrary, women, particularly in the form of Salander, are powerful survivors. She fights back, not merely accepting her circumstances.

As Melissa Silverstein of Women & Hollywood wrote in Forbes,

As my friend playwright Theresa Rebeck says, “The world looks at women who fight back as crazy.” We constantly see movies, TV shows and plays where men commit violence against women. That’s our norm. Here we have a woman who is saying no more and exacts revenge. Larsson is very clearly saying what we all know and believe. Lisbeth is not crazy. She is a feminist hero of our time.

Violence against women is a pervasive issue. According to the anti-sexual assault organization RAINN, “every 2 minutes in the U.S., someone is sexually assaulted; nearly half of these victims are under the age of 18, and 80 percent are under 30.” And in Sweden, the problem is just as pervasive. Larsson states that “46 percent of the women in Sweden have been subjected to violence by a man.” We must not continue to brush these crimes aside. The original Swedish title of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (both the book and the film) is Män Som Hatar Kvinnor, which translates to “Men Who Hate Women.” I’m glad that Larsson devoted his books to shedding light on misogyny in society.

A provocative and haunting film, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo is worthy of watching for Rapace’s subtle yet powerful performance. It’s rare for an audience to see a strong, self-sufficient woman on-screen. It’s even more unusual for a movie to address the stigma of sexual assault as well as the complexity of gender roles. Watch the movie and read the book. Get acquainted with Lisbeth Salander; she may be the most exhilarating, unconventional and surprising character you will ever encounter.

Written and directed by Catherine Breillat, Bluebeard (Barbe Bleue) likely explores the same themes that Angela Carter highlighted in her retelling, “The Bloody Chamber.” Read the original fairy tale by Charles Perrault here and Angela Carter’s version here.

Having built a career on provocative, sexually explicit yet cerebral fare (“Romance,” “Sex Is Comedy”), Catherine Breillat shocked auds with her 2007 period piece, “The Last Mistress,” because it was not all that shocking. Now the Gallic helmer’s latest, “Bluebeard,” features considerable blood but no sex. This offbeat but compelling take on the tale, arguably the first serial-killer yarn, emphasizes sisterly bonds but still gets to the original story’s heart of mysterious darkness with impressive results.

The New York Times‘ Manhola Dargis:

In “Bluebeard,” a sly rethink of the freakily morbid fairy tale, the filmmaker Catherine Breillat makes the case that once-upon-a-time stories never end. Divided into two parallel narratives — one focuses on Bluebeard and his dangerously curious wife, while the other involves two little girls in the modern era revisiting the tale — the movie is at once direct, complex and peculiar. It isn’t at all surprising that Ms. Breillat, a singular French filmmaker with strong, often unorthodox views on women and men and sex and power, would have been interested in a troubling tale about the perils of disobedient wives. Ms. Breillat never behaves.

You can watch the trailer here.

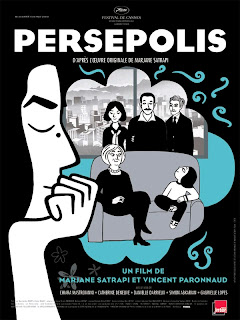

Persepolis. (2007) Written and directed by Marjane Satrapi and Vincent Paronnaud.

Persepolis is adapted from the autobiographical graphic novels written by Marjane Satrapi (which I haven’t read), and represents the first graphic-novel-as-film. Other graphic novels have been made into films, but none (to my knowledge) have remained as true to form as this. Visually, the film is lovely, stark, and at times deeply disturbing.

In Persepolis, we meet Marjane, a young girl living in Iran at the time of the Islamic revolution of 1979. The society changed drastically under Islamic law, as evidenced by Marjane’s teacher’s evolving lessons. After the revolution, in 1982, she tells the young girls, who are now required by law to cover their heads, “The veil stands for freedom. A decent woman shelters herself from men’s eyes. A woman who shows herself will burn in hell.” In typical fashion, the students escape her ideological droning through imported pop culture: the music of ABBA, The Bee Gees, Michael Jackson, and Iron Maiden.

In Persepolis, we meet Marjane, a young girl living in Iran at the time of the Islamic revolution of 1979. The society changed drastically under Islamic law, as evidenced by Marjane’s teacher’s evolving lessons. After the revolution, in 1982, she tells the young girls, who are now required by law to cover their heads, “The veil stands for freedom. A decent woman shelters herself from men’s eyes. A woman who shows herself will burn in hell.” In typical fashion, the students escape her ideological droning through imported pop culture: the music of ABBA, The Bee Gees, Michael Jackson, and Iron Maiden.

While the film is a personal story, it does offer a concise history of modern Iran, including the U.S. involvement in the rise of Islamic law and in the Iran-Iraq war. This time in Iranian history is especially important right now, with the disputed re-election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and the ensuing protests. One scene in particular depicts a group of people protesting when a young man is shot, bleeds to death, and is hoisted over his fellow protesters’ shoulders–eerily reminiscent of what happened with Neda Agha Soltan, whose public murder has rallied the Iranian protesters and people all over the world.

The history of Iran, while it determines the course of Marjane’s life, really is a backdrop—especially in the second half of the movie. In other words, the film is more about the experience of one woman than a documentary-style account of Iranian history. Once Marjane escapes the society she grew up in, her problems become much more ordinary for a Western audience, more commonplace. She vacillates between different crowds of people. She falls in love and has her heart broken. She feels angst and confusion over who she is and what she wants. She goes home to Iran for a time and, like so many others, ultimately finds she cannot return home.

As evident in the film, Satrapi grew up in a wealthy, educated, progressive Iranian family. They sent her to Vienna as a teenager so she didn’t have to spend her adolescence in such a repressive society, and because they feared what might happen to such an outspoken young woman there. While acknowledging her privilege, not many women in circumstances other than these would be able to accomplish what she has.  Satrapi isn’t afraid to show missteps she makes in growing up, either. Young Marjane learns that her femininity, even when repressed by law, offers great power—and shows how she misuses that power. Missing her mother’s lesson at the grocery store about female solidarity, she blames other women for her troubles (“Ma’am, my mother is dead. My stepmother’s so cruel. If I’m late, she’ll kill me. She’ll burn me with an iron. She’ll make my dad put me in an orphanage.”), and falsely accuses a man of looking at her in public to avoid the law coming down on her.

Satrapi isn’t afraid to show missteps she makes in growing up, either. Young Marjane learns that her femininity, even when repressed by law, offers great power—and shows how she misuses that power. Missing her mother’s lesson at the grocery store about female solidarity, she blames other women for her troubles (“Ma’am, my mother is dead. My stepmother’s so cruel. If I’m late, she’ll kill me. She’ll burn me with an iron. She’ll make my dad put me in an orphanage.”), and falsely accuses a man of looking at her in public to avoid the law coming down on her.

Persepolis is, in every definition of the term, a feminist film. There are strong, interesting female characters who sometimes make mistakes. The women, like in real life, are engaged in politics and struggle with expectations set for them and that they set for themselves. They have relationships with various people, but their lives are not defined by one romantic relationship, even though sometimes it can feel that way.

As much as I like this movie, I can’t help but write this review through the lens of an interview Satrapi gave in 2004, in which she claimed to not be a feminist and displayed ignorance of the basic concept of feminism. I simply don’t believe gender inequality can be dissolved through basic humanism—especially in oppressive patriarchal societies like Iran. I wonder if feminism represents too radical a position to non-Westerners, and if her statements were more strategy than sincerity. Making feminism an enemy or perpetuating the post-feminist rhetoric isn’t going to help anyone. That said, this is a very good movie and I highly recommend it.

The official trailer:

A couple of good articles about women’s role in the recent Iranian protests:

The Nation: Icons of the New Iran by Barbara Crossette

Feminist Peace Network: Memo to ABC: Lipstick Revolution FAIL

Post your own links–and thoughts about Persepolis–in the comments.

The Stoning of Soraya M. (2008). Directed by Cyrus Nowrasteh. Screenplay by Betsy Giffen Nowrasteh & Cyrus Nowrasteh (based on the book by Freidoune Sahebjam). Starring Mozhan Marno, Shohreh Aghdashloo, and James Caviezel.

Read The Huffington Post’s laudatory review and Jezebel’s excellent coverage of this timely film, which debuted in the U.S. this past weekend.

Watch the trailer: