This guest post by Kathryn Diaz appears as part of our theme week on The Terror of Little Girls.

In the great monster mash team of terrifying children, the vampire girl is varsity captain. On the one hand, they are dolls forever: trapped in their prepubescent bodies for hundreds to thousands of years without a single curl losing its bounce. On the other hand, with hundreds of years of life come hundreds of years of experience, knowledge, even maturity. The great perverse contradiction of an innocent but worldly, pure but sexual girl beings that characterizes so many fantasies and paranoias about young girls comes to a larger than life reality with one part vampire bite added to sugar, spice, and everything nice. It’s a lot to take in. Especially since in practice, these horrific fantasies are much more complicated than they appear and often pack a harder punch than their makers bargained for. Because little girls aren’t dolls for men to play with. They have wills of their own, and one day they learn to use it with bite.

It’s worth mentioning that one of the most famous vampire girls in cinema is coveted by her makers for her girlishness. Claudia isn’t just raised in the vampire way by Louis and Lestat in Interview with the Vampire, she’s worshiped for it. From the moment she transforms from a dirty, malnourished urchin to a cherub-like creature that asks ever so sweetly for more blood, she is the apple of Lestat’s eye. He is charmed by her coquettish innocence and praises such traditionally feminine virtues as neatness. Even before this moment, Claudia represents hope for Lestat and Louis’ relationship and redemption for Louis’ conscience because of her apparent youth and innocence.

In the montage that depicts Claudia “growing up,” we see her surrounded by servants, dresses, and frills and privileges fit for a princess. One in particular has her standing on a pedestal in the center of a room–for trying on dresses, of course. But the imagery of her as a worshiped being, or perhaps a favorite doll upon a shelf is not to be dismissed. As Louis explains in his voice-over, “To me she was a child” and “to Lestat, a pupil.” Claudia is, in short, made into the desires of her makers.

This is not an uncommon motif in the vampire genre, or even in the broader spectrum of monster-making. Dracula makes his brides after his lusts, Frankenstein’s creature asks for a bride after his loneliness. Louis and Lestat are in good company, but Claudia manages to break away from the pack of female creations by sheer force of will and determined disobedience. She is more than discontent, she is proactive. And she isn’t alone.

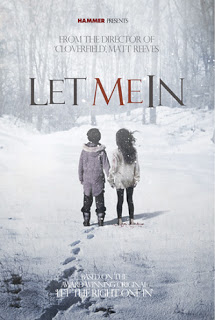

Like all vampires, Eli was made by someone once upon a time. Both Let the Right One In and the American remake Let Me In are purposefully vague about the details of her origin story, but we can depend on the basic aspects of the common vampire myth to fill in some of the blanks. We don’t know what happened to her maker either, but their absence and Eli’s lack of preoccupation with them seems to support the idea that she doesn’t miss them. Instead, Eli roams the world as she chooses, finding human partners to help her survive along the way. She has broken away from the hold of whatever agenda she was created for and spends the film working her own. Like Claudia, Eli rebells against the routine of her lifestyle for her own desires. Her protector, Hakan, is comfortable in the way of their life and in their solitary household. He has a possessive devotion to Eli as evidenced by his behavior when the subject of Eli’s new friend, Oskar, comes up. Eli is quick to remind him that while he may play the role of her father to the outside world, he doesn’t have any authority authority over who she chooses to spend her time with.

Claudia’s rebellions are much less cooly carried out, perhaps in part because they are nearly always to some degree, unsuccessful. Like Eli, Claudia tries to gain some ownership of her identity through trying to control her appearance and how she is perceived by others. She tries to take her “perfect” doll-like appearance into her own hands by cutting her hair. She dresses older and when she is alone with Louis, she adopts the countenance of a woman as old as she feels rather than that of the child she looks like. These are different but comparable tactics to Eli insisting that she is twelve and maintaining an awareness and hold of childlike things such as puzzles and games. Both of these girls do not want to be overridden into someone else’s idea because of their circumstances. But Claudia cannot get what she wants out of her actions. Her hair grows back when she cuts it, strangers refuse to take her seriously when she dresses older, capturing and drawing grown women does not transform her by any manner of alchemy. But Claudia does accept her fate without a fight, perhaps lest Lestat mistake her for the dolls he buys her every year. So she breaks the rules, pushes her luck, and she tries her hand at a little bit of vampire-on-vampire murder. When Louis starts to show how uncomfortable he is about the deed, Claudia tells him “he deserved to die” and later, that she did it “so we could be free.” She knows, perhaps even better than Louis, that he is a created monster like her too.

Claudia and Eli are both determined, willful girls strong in their sense of self and what they want. It also feels fairly safe to say that the horror derived from them is from a fear of how much they can do and accomplish on their own terms and the consequences of getting on their bad side. I mean, these girls aren’t afraid of things getting a little bloody. At all. But it’s also worth noting that both of these films are invested in their perspectives. Interview with the Vampire is almost devoid of human characters and Let the Right One In is about Oskar and Eli’s growing relationship together. The loved ones in their lives adore them, seek comfort in them, and stand beside them. We read Eli’s notes and watch her quiet excitement as she gets back in touch with what she loves in the world. We see Claudia’s smile as she dances with Louis in France and her forlorn expressions as they share in their loneliness together. As frightful as the lengths these two girls will go to are, it’s hard not to want them to succeed. We are made to understand the frustration and anguish of their positions and the ache of hoping for something as universal and fundamental as control over one’s life and identity. Even though one of these girls succeeds in her story and the other does not, it says something that these films are able to clearly articulate that a little girl is not just pretty and cunning and mysterious. A girl is also every bit as complex and full of yearning as her older male counterparts. She can be as fierce as anything else that goes bump in the night. And sometimes? She’ll win. And you’ll be glad she did.

Kathryn Diaz is a writer living in Houston, Texas. She is currently pursuing a B.A in English at the University of Houston. You can follow her at The Telescope for more of her work.