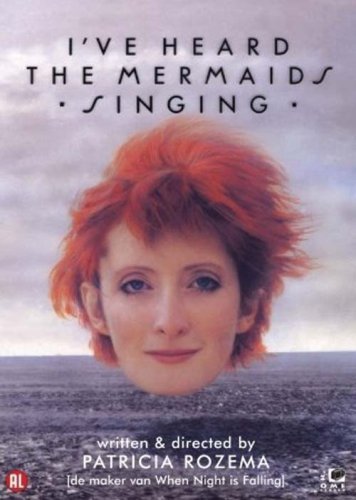

This post is inspired by Alison Nastasi’s “50 Essential Feminist Films,” an excellent survey of films that is a kind of resource guide for those of us interested in exploring feminist film history. Though not exhaustive, Nastasi’s list is an exciting place to extend the conversation about the ways that feminist questions and concerns have been depicted in films in and outside of Hollywood in the past several decades. What’s more, this list is also a site for discovering films I didn’t even know to look for. I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing, which Natasi ranks at #45, is one I might not otherwise have found. I’m so glad that I did.

The Canadian director Patrica Rozema directed this quietly charming film, which stars Sheila McCarthy. McCarthy plays Polly, whose videotaped confession frames the story and immediately establishes our curiosity. What crime could this anxious and seemingly guileless woman have committed? Polly is in her early 30s and enjoys a solitary life filled with frequent bike rides to various spots around Toronto, which she eagerly absorbs in her photography. She develops the pictures in her darkroom, and we see her still images enlarged by her imagination into elaborate fantasies wherein she can fly like a bird, engage in erudite conversation about psychoanalysis, and conduct magnificent symphonies. Although there is something slightly melancholy about her, Polly appears content with the simplicity of her life.

As she tells the video camera, “It all started” when she begins working as the “Girl Friday” for a curator, Gabrielle. Polly rapturously describes how taken she is with Gabrielle, who Polly exclusively refers to as “the curator.” Gabrielle is sophisticated, confident, and serious. Most of all, she is generous toward Polly, who falls under a spell of childlike adoration. Remarkably, their dynamic is one of mutual respect, even despite their differences. Gabrielle appreciates Polly, and offers her a permanent position. However, Polly is as innocent and naïve as Gabrielle is weary and cautious, and this contrast intensifies when Mary enters the scene. An artist and former lover of Gabrielle’s, Mary is young enough to make Gabrielle feel too old to be with her, and we soon learn that the curator has an inner life that is fraught with insecurity about both aging and art.

On the latter, Polly feels a kinship with Gabrielle, who drunkenly confides to Polly that despite her accomplishments and status, she craves not to “die with her body.” Gabrielle tells Polly that she desires the immortality of creating a beautiful painting that will endure after she is gone. Polly’s openness and curiosity is a marked contrast to Gabrielle’s self-centeredness, but the intimacy of this scene makes it hard not to sympathize with both characters. When Gabrielle expresses shame around have her paintings rejected for acceptance in a university art course, Polly lovingly asks if Gabrielle will show her a painting. Gabrielle is flattered by her request, and opens the door to a room with a shining canvas that Polly finds enchanting. Even though Gabrielle and Mary are lovers, it is with Polly that Gabrielle can express her deep yearning to be known as an artist.

At the risk of spoiling this film any further, I’ll just say that what follows is an act that Polly commits with the most heartfelt of intentions but leads to a series of betrayals compelling her to document her account on video in the hopes of sharing the truth. Though not fundamental to enjoying nor understanding the film, it is interesting to revisit the poem from which the title of Rozema’s film is lifted: “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” Just like T.S. Eliot’s narrator, Polly dares to “disturb the universe.” In so doing, she illustrates the sacrifice inherent in sharing one’s art.