Written by Erin Tatum.

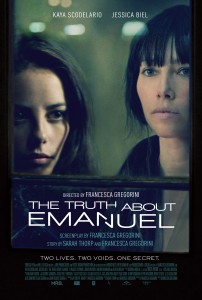

I have a thing for creepy/taboo relationships in fiction. All I had to hear was “baby obsession” and I was sold on The Truth About Emanuel. I’m also familiar with Kaya Scodelario from her Skins years and I was curious to find out if she had range beyond troubled teen queen. On that front I was a bit underwhelmed. Thankfully, the true focus of the story extended far beyond her.

Scodelario plays 17-year-old Emmanuel, a jaded teen disillusioned by the death of her mother during her birth, resulting in perennial survivor’s guilt that always seems to crop up around her birthday. Guess what time of year it is! In her opening internal monologue, she describes how the doctor brought her back to life with “the same rhythmic motions he had used to jerk himself off that morning.” This is a nit picky thing, but I’m so sick of sexual omniscience and perversity being a marker of worldliness or psychopathic tendencies in teens. Psychology and sexuality do tend to go hand in hand (no pun intended), but did we really need such an irrelevant detail? Also, since when can you evoke suspected obscure third-party masturbation as a metaphor for your own sadness? She literally says “he came and I came… back to life.” That just sounds unsanitary. Was he masturbating and performing CPR on an infant at the same time?

Anyway, Emmanuel’s life is turned upside down by the arrival of her new neighbor Linda (Jessica Biel) and her baby daughter Chloe. Before that, we get a nice preview of the forthcoming dysfunction as Emanuel bizarrely accuses her stepmother Janice (Frances O’Connor) of thinking she’s a lesbian and passively aggressively insinuates that she has had sexual dreams about Janice. As someone who relishes queer undertones, even I have to say I was baffled by the repeated references to Emanuel’s supposed sexual ambiguity. Same-sex desire seems to exist to fan the flames of anxiety around the unfulfilled Oedipal complex. More on that later.

Linda is simultaneously evasive about Chloe, trusting Emanuel to be in the house alone with her despite never introducing the two. Linda and Emanuel bond one-on-one and it’s intentionally left unclear whether Emanuel is substituting her as a mother figure or developing romantic interest. The plot synopsis also piles on by pointing out the physical similarities between Linda and Emanuel’s late mother. Yes, because if I were mourning my dead mother and feeling responsible for her death, obviously the only logical way to cope with things would be to lust after her doppleganger. I’m fascinated by the thematic exploration of incest as arguably one of the deepest social taboos, but I’m really not feeling this compulsive equation of parental grief in itself to depraved Freudian sexual confusion.

To take some of the heat off the lesbian pseudo-incest, Emanuel has a boyfriend Claude (Aneurin Barnard) that she meets commuting on the train. It’s kind of a random place to have a romance and it screams try hard indie. The love interest aspect of this film in terms of Claude feels disjointed and doesn’t really add anything to the narrative, except to shore up Emanuel’s otherwise shaky heterosexuality. Clyde and Linda both spend a lot of time babbling reverent nonsense at Emanuel about her introverted mysteriousness to insist that the audience should continue to find her intriguing with very little character development. 21-year-old Scodelario has been stirring the rapidly cooling embers of stock manic pixie dream girl tropes (with the particularly offputting caveat of emotional unavailability) since she was 14, so the aloof informed attractiveness shtick is boring on a film-specific level and in the scope of her entire opus.

Something isn’t right about the baby from day one. Linda is initially reluctant to allow Emanuel to see Chloe and Emanuel frequently hallucinates ocean sounds or even rising water when near the nursery. We later learn this is an allusion to the peaceful swimming dream her mother had before starting fatal labor. It’s like a psychosis roulette! Emanuel soon discovers that “Chloe” is actually a lifelike doll, strangely contradicting a photograph she found earlier of Linda and her estranged husband holding a real baby. This is where a lot of critics checked out. The doll revelation is made 30 minutes in and the pacing of the remaining hour is admittedly clunky. If you can’t get past the LOL reflex of “I can’t believe they’re treating the doll like a real person,” this probably isn’t the film for you because everything after that becomes unbearably campy. And frankly, I think the impulse to treat things deemed inauthentic as laughable or not human exemplifies the callous ideology that the film is warning against. When viewed as a commentary on loss and mental illness, the story becomes poignant and heartbreaking.

Emanuel reacts to the doll with horror and disgust. Curiously, she stops short of questioning Linda, although she is mortified by and actively tries to thwart Linda’s attempts to introduce Chloe to the neighbors. Emanuel shrouds herself in secrecy as she and Linda develop a routine, caring for Chloe as if she were a normal infant. Her willingness to indulge Linda’s fantasy, perhaps a signal of her own dwindling sanity, increases as her infatuation with Linda intensifies. The parallel grieving metaphor here isn’t subtle. Emanuel always wondered what life would be like if her mom lived instead of her and she finds an unsettling possibility in Linda, surprisingly augmenting her guilt. By the same token, Linda states several times that she wants Chloe to grow up to be like Emanuel and sees Emanuel and Chloe as sisters, indicating that she perceives Emanuel as her child in a roundabout way. Emanuel appears to start independently believing in the realness of Chloe as she becomes more determined for her and Linda to rebuild their fractured families together, a shift cemented by her choosing to feed Chloe an actual bottle of milk when they are home alone.

Still, the lesbian element always remains forced back onto the periphery, for reasons I don’t understand. Emanuel’s stepmom even privately warns Linda that Emanuel might make a move because she didn’t have a mom and is therefore confused. Way to play on every gay stereotype ever. She awkwardly tries to confirm that Linda is straight and Linda hesitates for a second before we cut to the next scene. We get all of these cat-and-mouse subtextual moments throughout, but the weirdest thing is that none of it goes anywhere. Emanuel and Linda never act on their sexual tension, but it’s never denied or put to rest either. I question why that dynamic was included in the first place. Queer desire is demonized as facilitating incest and nothing more, which is extremely and almost needlessly unfortunate given the lack of narrative relevance.

Oh, and Janice (the stepmom) confides to Linda that she’s infertile and that’s part of the reason for her uneasiness with Emanuel. No one in this movie can have a positive relationship to childbirth.

Things take an abrupt nosedive when Linda agrees to go on a date with Emanuel’s coworker, Arthur. Afterwards, she ignores Emanuel’s protests and excitedly suggests Arthur take a peek at the sleeping baby. He quickly points out that it’s a doll, shattering Linda’s carefully constructed bubble. She recognizes the baby as fake for the first time and immediately flies into a panic, demanding that Emanuel tell her Chloe’s true location and accusing her of stealing Chloe. I find it hard to believe that someone as delusional as Linda would snap back to reality the second someone brought up the tiniest shred of rational doubt, but Biel’s acting is phenomenal in this scene. Most intriguingly of all, Emanuel protectively cradles Chloe as both Arthur and Linda berate the doll as a lie, suggesting that she’s just as far gone if not more so than Linda.

Arthur drags Linda away and Emanuel curls up on the floor with the doll, suddenly finding herself swimming underwater. Emanuel’s mom appears in the distance and Chloe comes to life. The two of them swim away together, leaving Emanuel alone. After Emmanuel passes out and wakes up in the hospital, Linda’s husband explains that the doll was the culmination of Linda’s mental breakdown following the death of their infant daughter. Motherhood is just so healthy. Linda is sent to a mental institution.

Undeterred, Emanuel enlists the help of her boyfriend to break Linda out. She tells Linda that Chloe isn’t okay, but she shouldn’t worry because Chloe is with her mom now. Together, they bury the doll on top of Emanuel’s mom’s grave and gaze at the stars together, their broken pasts now finally at peace.