This is a guest post by Mara Gasbarro Tasker.

As much as I would love to have Liam Neeson running around after me all day, I’d rather it not be because I had been abducted and stuck tied to a chair. But this seems to be one of the only ways that we get to see women on screen in today’s high stakes thrillers. In my last post, I talked about the use of rape in storytelling and its commonplace usage as a catalyst in stories. Today, I wanted to shed some light on the use of kidnapping the female body for the purpose of narrative drive.

Women have limited opportunities on screen; we all know this to be true and there are a number of reasons that this is the case. But looking beyond that fact, I think it’s important to examine the effects of these images. I don’t deny that I love fast-cutting action films. But when thinking back to a significant number of action, thriller, and psychological films, it’s challenging to think of some that don’t include the taking of a female body.

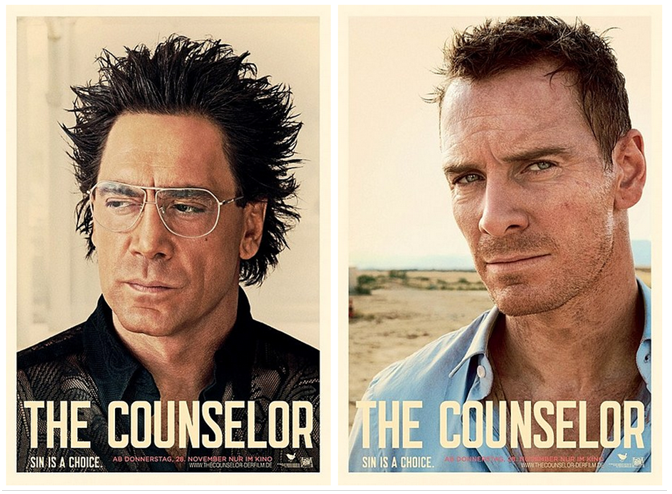

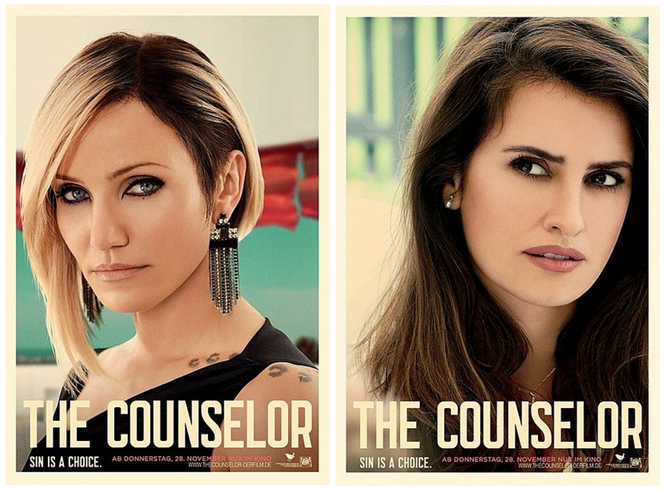

Take Blake Lively in Savages, or Penelope Cruz in The Counselor, or Maggie Gyllenhaal in The Dark Knight, or Kristen Rudrud in Fargo, or Maggie Grace in Taken.

Each of these films and many, many more, use the kidnapping of a female character, of the female body, to raise the stakes. It appears we’re worth something valuable to the story. But as pieces, not players.

What’s concerning with these roles is that they perpetuate the quiet and commonplace commodification of a woman’s body, and it’s become the main function of our characters on the screen. This technique of taking someone hostage has been employed in well done ways before. Looking back to The Searchers, Natalie Woods’ abduction by the Comanches still plays on classic weaker female characters, while actually bringing about the space in the film for in depth character reveals and an odyssey that exposes many people over the course of 120 minutes. In films like The Dark Knight, it feels excusable to play on classic comic book themes of revenge, taking a female character hostage, and having some heroic and uniquely strong man come to save her. It’s a model Disney employs in many of its cartoons as well.

But this to me is the part we should pay attention to. When we don’t get to be headstrong, sexy scientists with daddy issues, we’re locked away. Because evidently we’re worth a lot, which while flattering, also insinuates that we are prizes that can be traded, bought, or stolen. In any film of the above mentioned genres, it’s safe to assume that at some point, the concerned wife, sexy girlfriend, or charming daughter will be kidnapped. When the body is used as a bargaining chip, the images that flood our minds are women tied to chairs, kidnappers holding phones to our crying faces, and makeshifts rag gags in our mouths. It seems strange that Jason Bourne and Ethan Hunt can work their way out of any god-given scenario but women, even the smart ones we encounter in films, can’t seem to stay out of trouble.

The problem is that this storytelling device has been overdone and like violence, is now often used as a lazy attempt to raise the stakes and create tension. Everyone who loves anyone knows that losing that person would drive them mad. But does it always have to be the woman?

David Foster Wallace, in his heartbreaking series of shorts in Oblivion, describes all human beings as being comprised of an infinite number of eternities. It’s one of my favorite ways to understand people now. And so I ask, if that’s the case, if we’re all made up of an infinite matrix of capable emotions and therefore reactions, why has film, an art that encompasses so many senses, boiled itself down to simplistic storytelling where the best way to ignite anger or the want of revenge in someone is to “take” his woman?

Let’s take a look at a few more contemporary films to illustrate this point, starting with Taken, and of course its sequels. Round one of Taken dishes up a nice storyline of a young American woman who travels abroad with her best friend, makes one ill-advised move and spends the rest of the film being sold into sex slavery. Meanwhile, her father, who thank god is Liam Neeson and has a very special set of skills (that he’s allowed to have, as male protagonists are), comes to save her. In Taken 2, shock me, shock me, Liam’s wife gets kidnapped. In both films, it’s the stolen woman’s body that gets things moving and that allows this stretch of space on screen for our hero.

In Prisoners, a powerful film with incredible performances, who is it that goes missing? Who is made voiceless? Who is rendered a token of something? While in a film like this it is integral to the reveal of character and mystery, again we should ask – why at the cost of a young woman? Hugh Jackman’s character Keller Dover embarks on a manhunt when his daughter is kidnapped with her friend. Because why not? How many models have we seen where it’s not a female? Man on Fire uses the same technique- a young woman, a young child, taken for sinister reasons because by simply holding on to her, our usual antagonists can cash out and manipulate their adversary, who we’re in turn cheering on to “recapture” the victim.

There are, of course, comedic twists like Fargo, which also happens to be a film I absolutely love. But again here, we have a female role whose purpose, while hilariously treated at times, is to be stolen, missing, and the tool in the story that the plot revolves around.

My purpose in highlighting these tropes is that we must pay attention to the trade of the female body. If any characters in the film have a qualm, it is often settled by “taking” the other person’s loved one, and this is more often than not, a woman in their life. Our roles, as reflected back at us on screen, have limited dialogue because there is usually a rag in our faces keeping us from speaking.

We’re fed images of a woman who is made to disappear at some point in the film, left without a voice and made entirely helpless until the male protagonist comes along. This is plot device that is designed to distract from the fact that not enough story has actually been developed.

Remove the woman from this equation. You have character A wanting to get something from character B. There could be any number of mysterious ways to do this. Manipulation, lies, fights, theft, threats, coaxing. There are a thousand ways around the central and overused plot device of the female body. Personally, I think we’ve stop noticing. We’ve stopped paying attention to the fact that we are treated a commodities on screen. Not a far cry from the use of rape as a narrative catalyst, what does constantly kidnapping a woman say about what we are? We have become the stakes.

We have complacently accepted that a crime against a woman is rarely a crime against her. Rather, it’s an indirect attack against her husband, boyfriend, or father. It is a violation of the male character when the female is traded in some illicit way. Even intelligent, scientific, and clearly downplayed but sexy scientist characters somehow still find their way into these traps. We identify these crimes against women as crimes against someone else. This removes us from the responsibility of a committing a heinous crime against a female figure and makes her simply a piece in the malefaction rather than the recipient of the aggression–which she is.

This rids us of human qualities. It rids women of screen time, of dialogue, of control. It once again quietly pushes us from roles as real people in film and in life, to props for narrative mobility. In using women in this way, we visually inform ourselves over and over and over again that our only option is to wait for someone stronger to come. . We’re the thing that they need to get back.

Liam Neeson, come running for me. Anytime you want. But I’d rather it be for love than because I didn’t have enough pepper spray on me to avoid a really shitty day.

*Side note worth mentioning – in trying to find images for this article, it was surprisingly hard to find pictures of the women in their hostage situation. It’s almost like it never happened. Or you find porn.

Mara Gasbarro Tasker is a filmmaker based in Los Angeles. She’s currently working as an Associate Producer at Vice Media and has co-created the Chattanooga Film Festival, launching later this spring. She holds a BFA in Film Production from the University of Colorado at Boulder. She is directing a grindhouse short in April and is still mourning the end of Breaking Bad.