This guest review by Deborah Pless appears as part of our theme week on Cult Films and B Movies.

I fell in love with Boondock Saints the summer that I turned sixteen, about four days before I went off to live and work at a Christian summer camp for eight weeks – a torturously long time when you’ve just fallen in love with the most profane and violent movie possible. I was told that I shouldn’t watch it, that I couldn’t watch it, because it was too violent, too swear-y, too much for my faint little heart to take. I told them to eff themselves and watched it anyway. And I fell in love instantly.

It was a long lasting love affair too. I had the poster hanging above my bed, I still own a copy on DVD, and I saw that film so many times that I could recite it in real time as my college roommate watched in horror. I even went to see the sequel. In theaters. On purpose.

But it wasn’t until last year, when I started to write out a list of my all-time favorite movies that I realized something important: I might love Boondock Saints, but it doesn’t love me back. Or, specifically, it doesn’t love my gender. That was when the romance started to fade.

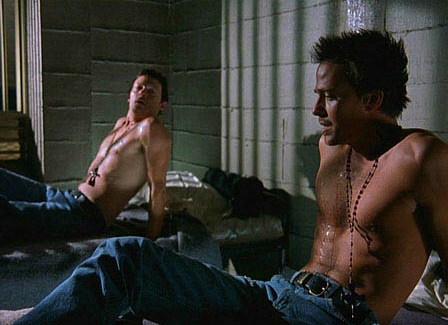

To back up a little, Boondock Saints is a cult shoot-em-up film released in 1999 and written and directed by Troy Duffy. It stars Sean Patrick Flanery and Norman Reedus as the McManus twins, two good old Irish boys living in South Boston who receive a message from God to go kill gangsters. Which they then proceed to do with alarming vigor and good humor. They’re pursued by Agent Smecker, played by Willem DeFoe, and helped by good friend Rocco, played by David Della Rocco.

Also, Billy Connolly turns up as a terrifying hit man known only as “Il Duce,” and Dot-Marie Jones makes a brief cameo as Rosengurtle Baumgartner, who kicks one of the boys in the crotch. But I digress.

The film is weird and violent and profane, like I said. The basic premise, that Connor (Flanery) and Murphy (Reedus) are on a holy mission to rid the world of evil is both strange and deeply non-Biblical, but there is a thrill to it that makes you want to believe. The plot kicks off when the boys are involved in a bar fight with two enforcers for the Russian mob. After the fight, the mobsters go track down our heroes and try to finish the job, but Connor and Murphy get the drop on them (literally), and kill the two men.

Agent Smecker is then called out to figure out what the hell happened. Smecker, who is inarguably DeFoe’s best and most interesting character to date, deduces the exact events effortlessly and is proven right when the two boys show up at the police station, turn themselves in, and claim self-defense.

The story would end right there if during the night spent in jail, the two men didn’t receive a vision from God. A mission, you might say, that calls them to “Destroy that which is evil, so that which is good may flourish.” This all tracks in with a sermon shown in the beginning of the film that cites the murder of Kitty Genovese as a sign that good men must do something to stop evil from spreading. All well and good, but I’m not sure the priest was calling for mass murder.

Which is precisely what happens. Connor and Murphy start picking off members of the Russian and Italian mobs, with a little help from their friend Rocco, a low-level numbers runner. They get so good at it, in fact, that Smecker is at a complete loss and the mob is running scared. It all comes to a climax when they try to take out the Don of the Italian mob in Boston, get captured, and come face to face with the man hired to kill them – Il Duce. Except Il Duce is actually their father, and the men happily reunite to go off and kill another day.

Like I said, it’s a weird, violent movie.

There are, in all honestly, a lot of things worth discussing with Boondock Saints, from the way it is one hundred and ten percent a white, male fantasy of justice and badassery, to the fact that it’s so Biblically inaccurate as to be kind of painful, to Agent Smecker as one of the most interesting gay characters to grace the silver screen, to the fact that it’s honestly just a very strange story, chock full of coincidences and arguably terrible writing that somehow becomes awesome instead of cliché. But let’s focus in for a minute on what turned me off of it. Let’s talk about the ladies.

Or, rather, let’s talk about the lack of them. In point of fact, the women of Boondock Saints are most notable by their absence. I can count the number of named female characters on one hand, and none of those characters appear in more than two scenes. That’s actually a false representation as well, because only one of them appears in more than one scene at all. Of all of the female characters in the film, not a single one receives more screentime than the scenes of Agent Smecker in drag toward the end of the film.

That is bad enough in and of itself, but there is also the actual characters to consider. Of the female characters shown or mentioned, one is an unnamed stripper (who, ironically, is the most visible woman in the film, appearing in two whole scenes), two are junkies and sluts (according to Rocco), and one is Rosengurtle Baumgartner, an avowed lesbian who we are supposed to laugh at for taking offense to one of Connor’s jokes. She kicks him in the nuts. He deserves it.

There are two more women of note in the story, but both had their stories cut down in the final version of the film and appear mostly in the deleted scenes on the DVD. One is Connor and Murphy’s mother, who calls them to wish them a happy birthday, and the other is a nice girl outside the courtroom who gives the news cameras a completely convincing and not at all ridiculous explanation of why she is perfectly fine having seen someone shot to death right in front of her moments before.

Like I said, that’s pretty much it. There’s a waitress, a nun in a hospital, an Italian grandmother, and a female news reporter, but I genuinely struggle to think of any more female characters. At all. In the entire movie. It would seem that in the world of Boondock Saints, women are not just irrelevant to the narrative, but also virtually invisible. They just don’t seem to exist.

I suppose it makes sense, given that the film is a white, male power fantasy. Connor and Murphy are the ultimate slacker heroes, the guys we’re supposed to want to be. They have no formal education, but somehow happen to know about six languages fluently. They seem perfectly content living on the fringes of society, because tough guys don’t need furniture or shower curtains or functioning plumbing, I guess. They’re religious, but in the cool way. They don’t have to learn how to use guns, or find out where to buy weaponry, or even struggle as they assume their mission. They just effortlessly seem to know what they need to do and then do it. No fuss, no muss. Without a second of training they are the two most proficient hit men ever to grace the streets of Boston.

It’s a fantasy, and you can see why it would be intoxicating. They’re good at what they do. They’re cool. What they do is unassailably (within the context of the movie universe) right. They get to shoot people and have fun and laugh with their friends, and it’s fine because it’s all justified by God. They don’t kill women or children, so it must be okay, right?

Well, no.

The ethics of the film are one thing, but it says a lot about the world of the movie that it’s able to go nearly two hours without a single important female character showing up on screen. There are no women cops, there are no women in the mob, there are only a couple of wives or passers-by or maybe a drug-addled girlfriend or two. But no one who matters. The acting characters in the film are all overwhelmingly and vocally male.

Even the ethos of the characters, that they will destroy that which is evil, but leave alone the pure and blameless, is inherently sexist. Because when they say pure and blameless, what they mean is the women and children. In this universe, women are not even people enough to do things wrong. We do not have enough agency even to commit evil.

But here’s the problem. I know all of this, and yet I still like the movie. I mean, I’m not in love with it anymore. The scales have lifted off my eyes, and I can see it for what it is – a bloated, self-aggrandizing, violent ode to vigilantism – but I still enjoy it.

How?

I think ultimately it comes down to something deeper. Something about how it took me eight years to realize that the movie was toxic for women. I genuinely did not expect this story, or really any story like it, to include women. I naturally didn’t even think to look for a female character to relate to, because it inherently assumed there wouldn’t be one.

Troy Duffy, aware of the criticism he received for this first film, included a major female character in the execrable sequel, Boondock Saints: All Saints Day. In it, Agent Smecker is gone and in his stead we have Agent Bloom (Julie Benz). But this is just another stunt meant to show how “progressive” and “totally not sexist” Duffy is. Bloom is relegated to a backseat role, and shown to be yet another innocent in the world. She’s a badass lady cop, but actually just a scared little girl who needs to be protected. And if she happens to fulfill a couple of fantasies about women in power suits and heels while she’s at it, then so much the better.

I wish I could tell sixteen-year-old me not to bother with this movie, that I should, for once, listen to my friends and back away slowly, but I don’t think I would, even if I were given the chance. Because as much as I now can see this movie for the sexist doggerel it is, it still has a place in my heart. It was the movie that taught me how much fun schlock flicks could be, the one that showed me that a movie doesn’t have to be good to be fun, and the movie that introduced me to one of my all time best friends. I wouldn’t take it back.

But I still wish it didn’t make me feel so gross inside.

Deborah Pless runs Kiss My Wonder Woman and works as a youth advocate in Western Washington. You can follow her on twitter, just as long as you like feminist rants and an obsession with superheroes.