This is a guest post by Giselle Defares.

The relationship between faith and love, the religious experience that is love, suffering and sacrifice, are themes that frequently recur in our pop culture. For some, love can be seen as the most powerful emotion we know, an emotion that can entail spiritual forces. In Breaking The Waves love and faith appear, despite the spiritual connotations, as matters proposed in a very earthly and physical manner. However, the age-old trope of the suffering woman who sacrifices herself so that the man triumphs is nothing new.

The Danish director Lars von Trier follows the beat of his own drum. Von Trier can be called many things: neurotic, shit stirrer and allegedly misogynist. In 2011 he was declared persona non grata after his ridiculous remarks in Cannes during a press conference for Melancholia: “I really wanted to be a Jew, and then I found out that I was really a Nazi… What can I say? I understand Hitler.” He took a “vow of silence” after this debacle. Not only did von Trier make various headlines in his career via his questionable, controversial statements, it’s also the result of the themes portrayed in his films. In most of his films the female characters are placed in violent and sexual situations. In an old interview with The Guardian, Von Trier said “Basically, I’m afraid of everything in life, except filmmaking.” Right.

Breaking the Waves centers round a strict Calvinist community in rural Scotland. Bess McNeill (Emily Watson) is a young woman who expresses her piety by cleaning the church. Here she holds various conversations with God. When Bess wants to marry Jan Nyman (Stellan Skarsgård), an outsider who works on the oil rigs, the church elderly are hesitant. Nevertheless, the first weeks of their marriage are successful. When Jan needs to get back to work at the rig, Bess becomes emotionally unhinged and begs God to bring him back. As a result of a fatal accident on the rig, Jan is brought back to the mainland. He is completely paralyzed, and his life is uncertain; both Bess and “God” blame themselves for Jan’s situation. When she asks God for help, he answers with the question: “Who do you want to save, yourself or Jan?” Bess then makes the fatal decision to save Jan.

Whether or not it was the intent of von Trier, Bess is frequently compared to the Christ figure in a modern tragedy. Her sacrifice was for a higher purpose and “not in vain.” In Bible and Cinema: Fifty Key Films, Adele Reinhartz gives two basic criteria that a movie character must meet in order to be seen as a Christ figure: “That there be some direct and specific resemblance to Christ and that the fundamental message associated with the possible Christ figure has to be consistent to the life and work of Christ, and contrary to his message about liberation and love.”

On the basis of these two criteria Bess can be seen as the female representation of a Christ figure. Her love, like that of Christ, is selfless and knows no boundaries. Bess commits herself entirely to sacrifice her being for this selfless love, even if it leads to death. However, this form of sacrifice is soon to be regarded as a specific element in her life. Bess is easily persuaded by Jan, because “God” commands her to fulfill his wishes. Jan’s requirements are so also God’s requirements. Bess is obedient and submissive to the male power, which forces her to place herself in unpleasant situations trying to save a man.

A representation of this point can be seen in the middle of the film when Bess prays directly to a hospitalized Jan. Bess exclaims, “I love you, Jan.” Jan answers, “I love you too, Bess. You are the love of my life.” Both Jan and God have the same voice, thereby Jan and God are put on the same pedestal. The masculine is the divine, the women must be submissive therein.

The female suffering in Breaking the Waves is deemed more important than the female existence. Her role as sexual martyr is better suitable for Bess than the role that is expected of her: the patriarchal role of the woman. The religious community in which Bess is brought up is stifling and oppressive, in which male domination prevails in both the personal and public life of the community (the household and the entire commune is dominated by the elderly male church leaders).

The position of the women in this patriarchal community is determined by the male counterparts. The imposed position of the wife doesn’t sit well with Bess; in the first chapter she goes against the grain by marrying Jan in the church, then she speaks in the church, which is forbidden for women. They also ask the women in the community that they remain calm and adhere to their men. Not the whimsical Bess: she beats Jan as he arrives late to their wedding, and is hysterical when he leaves her to work on the rig. This latter characteristic, hysteria, is considered as one of the “weakest” properties of a woman. Alyda Faber, a theologian, states in Redeeming Sexual Violence? A Feminist Reading of Breaking the Waves: “Von Trier creates the image of Bess as sexual martyr through a peculiar valorization of feminine abjection as madness, formlessness, malleability, hysteria. This common reiteration of femininity as weakness.”

Although Bess has more difficulty with the role of sexual martyr, she fulfills the role better than the imposed patriarchal role of a woman. Von Trier uses Bess as a sinner and as a martyr; archetypes that enable that Bess – from a feminist theological approach- is seen as a Mary Magdalene. Von Trier also literally refers to Mary Magdalene in Bess. This happens in the dialogue in which God speaks to Bess: “Mary Magdalene had sin, and she is my beloved.” Bess is caught between the two paradigms where Mary Magdalene was stuck as the virgin and the whore.

Her character begins as that of a virgin, which fits into the mold created by the church until she persists throughout the film and turns into a “whore.” It starts with her sexual relationship with her husband, where she learns to give her love of God over to Jan. Her faith and love into “the word” God has been replaced by the belief in carnal love. Bess at one point states: “You cannot love words. You cannot be in love with a word. You can love another human being.” Her faith for the greater good is stronger than the word of God; this faith in love has led her to sexual freedom–from virgin to whore. Despite Bess being often compared to Mary Magdalene and represented as a Christ figure she remains an ordinary woman who only has to offer her goodness.

Watson is phenomenal in her role as Bess and she deservedly received an Oscar nomination. She truly carries the film and has great chemistry with Skarsgård in the first chapters. Her suffering is stretched throughout the film causing pain and simultaneously pity for her character. Admittedly, the plot is very thin and at times feels illogical. The other characters feel like cardboard cutouts but the film is saved by Watson as the whimsical Bess.

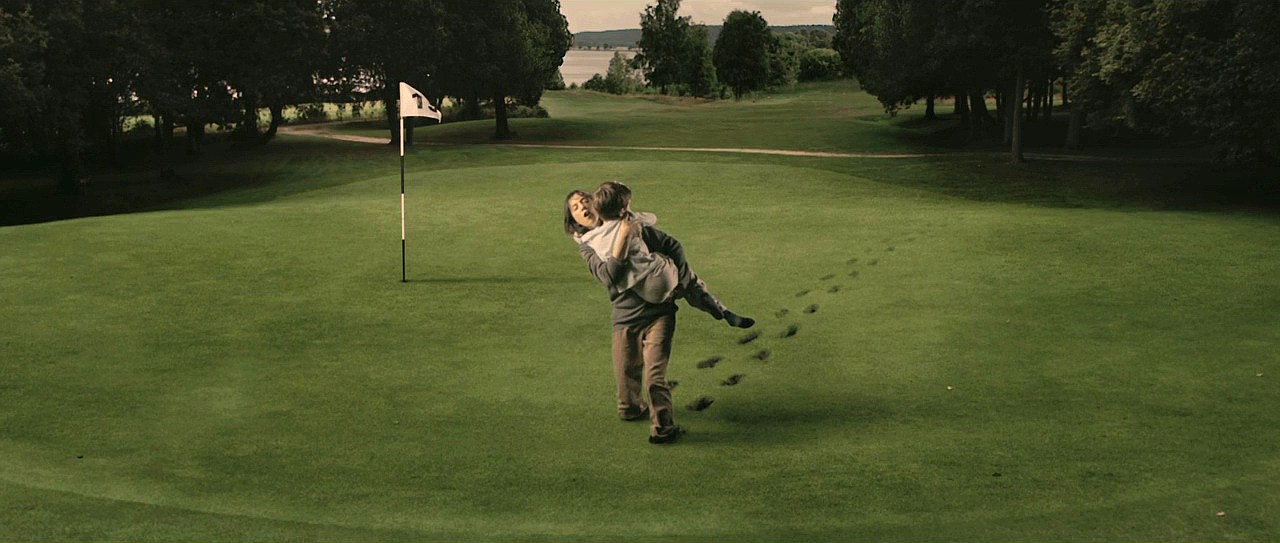

Von Trier styled the film almost like a documentary while using the handheld camera work of cinematographer Robbie Müller. The images are grainy, gray and pale in color, and there’s almost no use of a musical score. At first, the angular camera work doesn’t seem to work with the emotional storyline nor the strict and rigid community in which it takes place. Only with the announcement of a new chapter in the film are images shown that almost resemble moving paintings in beautiful, vibrant colors. As if the gaze of God descends on rural Scotland.

Breaking the Waves is, in essence, just an good old fashioned melodrama. It’s captivating and moving, but there’s no room for false sentiment.

[youtube_sc url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NmcnddpruXM”]

Giselle Defares comments on film, fashion (law) and American pop culture. See her blog here.