Written by Katherine Murray.

I’d really like to see more introspective films about the human experience where the humans experiencing things look like me.

Two weeks ago, I made a special trip downtown to see Whiplash, a movie that is every bit as good as its rave reviews have promised. Whiplash is tense and thoughtful, with skilful pacing and a stunning conclusion, and it asks challenging questions about the human experience. What is achievement? What drives us? What is the value of love and approval?

I absolutely recommend it – but that’s not what I want to talk about, here.

Aside from having an awesome, introspective story that deals in universal human themes, Whiplash has one other prominent feature – 99.9 percent of it is dudes.

The music student and music teacher at the core of the story are dudes, the other people in their band are all dudes, the main supporting character – who is the music student’s father – is a dude. Melissa Benoist is there for about seven minutes, cumulatively, and then the rest of the movie is about men grappling with big, important questions.

There’s nothing wrong with that – and, in popular cinema, there’s also nothing unusual about that – but it did make me wonder: why can’t we have more introspective movies about the human experience where the humans experiencing things are women?

Like, speaking as a woman, I am just as interested in big, existential, philosophical, and psychological questions as men are. I spend just as much time trying to figure them out, and they have just as much relevance to my life – but you wouldn’t really guess that from going to the movies.

Most of the time, when you watch a movie about how A Person should deal with X, the person is a man. To the point that it really stands out, when it’s not.

Gravity, for instance, aside from being a feast for your 3D glasses, is a story about how A Person should deal with loss. And it’s striking because the person is played by Sandra Bullock, and she’s on screen alone for most of the movie, grappling with universal human challenges like how to process grief, and how to find the will to live after experiencing trauma.

A lot of critics have argued that the film would have been better if it had just been about trying to fix a space shuttle without getting blown up, without making it a metaphor for how Sandra Bullock overcomes the loss of her child. It’s the loss and grief story, though, that takes this from being an action movie with a female protagonist – which is rare enough – to being an introspective movie about the human experience with a female protagonist – a genre that might be the rarest of all.

Depending which types of movies you’re analyzing, only 15 to 23 percent of top-grossing films have a female protagonist, despite the fact that women make up half the population. I’m willing to bet that, if we could easily cordon off and analyze the percentage of female protagonists in introspective movies about the human experience, the numbers would be even lower.

You’ve got your female action heroes, and you’ve got your female romantic leads – you’ve even got your female gross-out and/or buddy comedies, now. Occasionally, you even get your female everyman in the shape of Anna Kendrick. But, finding a woman as the stand-in for humanity is like finding a unicorn in a world where horses are already almost extinct.

If you look at this survey of Hollywood movies that came out in 2012, none of the ones with a female lead – except Brave, which is specifically about how there’s more than one acceptable way to be female – seem to be concerned with especially deep questions. This is the same year that brought us Cloud Atlas, Life of Pi, Looper, and ParaNorman – male-led stories with varying levels of introspection that focus on questions of history and human connection, belief, our capacity to learn to care for others, and compassion in the face of fear. Female-led movies in the survey include a couple of horror movies, an instalment in the Twilight franchise, The Hunger Games (which was good, but not that deep), and whatever the hell Snow White and the Huntsman was supposed to be.

Casually searching the internet for lists of existential movies, or movies about what it means to be human also returns a lot of movies about dudes.

That’s not to say that there aren’t deep, introspective movies with female protagonists. It’s just that they’re few and far between.

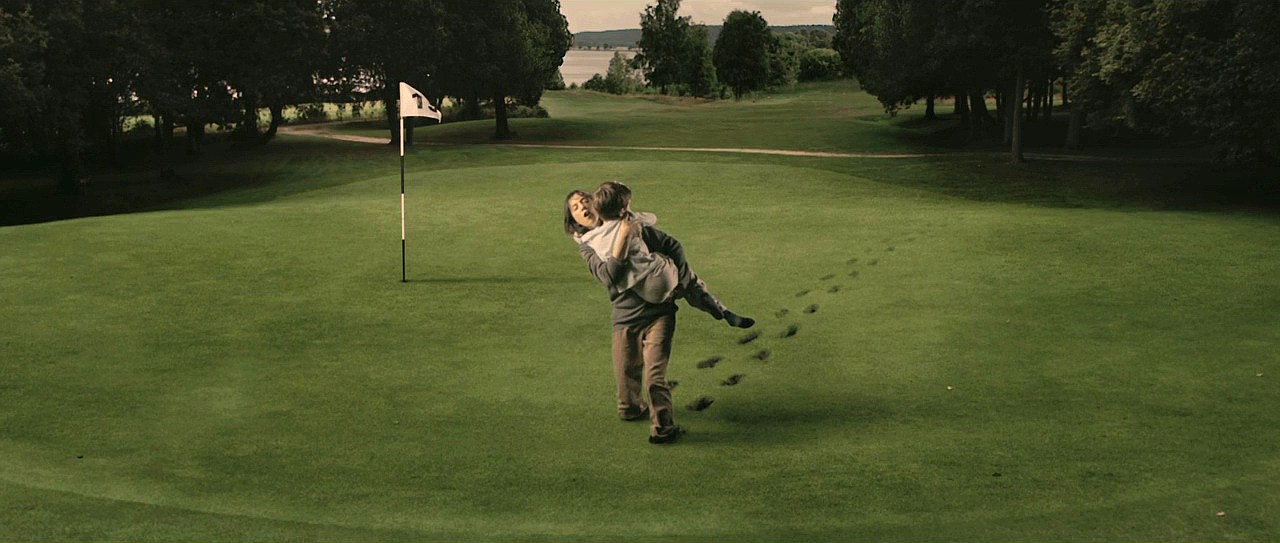

Slogging through Melancholia is about as fun as slogging through real depression, but it’s an introspective movie about a person who’s grappling with Big Questions concerning depressive realism, and whether pessimism is just good sense. Similarly, Black Swan is (arguably) a movie about a person grappling with identity, and how we reconcile with our shadow selves.

Le fabuleux destin d’Amélie Poulain – or, Amélie – is an introspective story about a person who struggles with shyness and how to take risks. And, it works at least as well as The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, which is about exactly the same thing, only starring a male protagonist.

So, there are some introspective films about the human experience that feature a female protagonist. But, why do these stories so often default to male?

The first explanation would be that most of the writers, directors, and producers working on movies are men, and therefore they’re more likely to create a male protagonist, because that’s the experience and perspective they’re most familiar and comfortable with.

Fair enough.

Though I hasten to add that Gravity, Melancholia, and Amélie were all written and directed by men, I think it’s valid for a story-teller to gravitate to telling stories about characters of their own gender, race, ethnicity, and sexual orientation. In some cases, it can even seem arrogant for story-tellers to presume to speak for people with different life experiences. That’s why it’s important to make room for stories told by people who’ve been underrepresented in media. You know, instead of making it as hard as possible for those people to get in on the action.

The second explanation also goes a long way toward answering the question, “Why does this even matter, Katherine?” and concerns the way that media presents “male” as standard and “female” as a special variation on “male.”

This is feminist criticism 101 and I won’t get into a long discussion of it, but everyone reading this blog understands that we live in a culture where “person” defaults to male a hell of a lot more often than it defaults to female – where being a woman is a marked status that denotes something other than a normal/average/neutral individual. Men and women are so used to seeing men as the default human that it can create a self-perpetuating cycle where writers keep reaching for “a man” when they mean to say “a person,” and the constant presentation of “a person” as “a man” on screen just reinforces that bias.

True story: I’m a woman, and I write things, and unless I specifically stop myself and take stock of what I’m doing, I default to male characters when I just need some random person. This is a thing that happens without malice or even intent, which is why it’s important to bring the pattern to conscious awareness.

Introspective human experience movies are typically more about A Person than they are about an individual with really specific characteristics; there’s a good chance that men are the default just because nobody’s thinking about it that much.

The third explanation, and the one that bums me out the most, is that there may be a perception that women either aren’t interested in or aren’t as capable of answering philosophical questions – something that’s also suggested by the unfortunate pattern where male actors are asked deep questions about the issues raised by their movies, and female actors are asked about their bodies and clothes.

Happily, the solution is the same no matter what the explanation is: we need to balance things out by creating more movies like Gravity, and Melancholia, and Amélie, where the stories are about people grappling with problems that people must face, and the people in question are women.

Just like it’s right that Matthew McConaughey should be able to star in a movie that’s specifically about masculinity (Mud), and a movie that’s about the abstract question of human selflessness (Interstellar), female actors should be able to take the lead in movies that are specifically about women as well as movies that are about people in general – because they represent both of those things.

So, where is the female version of Whiplash? It’s 50 years forward in time, when “person” has an equal chance of meaning “woman.”

Katherine Murray is a Toronto-based writer who yells about movies and TV on her blog.