This is a guest post by Mara Gasbarro Tasker.

Women have been speaking the hell up about gender in Hollywood this year and it’s been an awesome uprising to see. There has been an outpouring of voices across multiple demographics in media getting aggressive about the lack of opportunities available in all of its platforms.

What I find challenging, though, is the near constant focus on scarcity—the highlighting of women missing chances to shape film and media.

Rather than dive into the dark abyss of what feels a regression of women’s roles in the world, I decided to focus this article on what is working. On our successes. It’s much easier to model our creative designs and ourselves after things that we can see. So, if I had a beer right now, I’d pour it all out for my female homies who have trail blazed contemporary cinema. Here’s to the women who are “crushing it” in complex roles, who take every opportunity on screen to serve as their own victory of what can be done.

Last week I went to see this summer’s hot blockbuster Dawn of the Planet of the Apes. Now I will fully admit that this black and white, Italian Neorealism nerd fully enjoyed the ride. Much to my surprise, the film actually had me thinking of Shakespeare and Greek tragedy because— in terms of technicalities of story and character structure— they pulled some classic tricks out of the bag and that’s always cool with me. But during the movie there was one note that kept hitting the wrong key. Can someone, anyone, please explain why Keri Russell had only a one line backstory (that she lost her child as the Simian Flu spread) but then was never touched on again in the film? She was prescribed the role of mother, lone survivor, who clings to others and is a surprisingly talented nurse on a whim. But where in the film did she represent what a woman who has lost her child in a bleak new world might actually be like? There was a human being missing in her character.

(Also brief aside, ladies we’re not really going to survive the apocalypse based on the ratio presented in the film. Because, uterus.)

This article is not one that will chronicle those empty characters. This is for all the badass mamas out there—the honest mother roles that women have nailed. Hopefully this will present a case for why we need a million more. Here’s to the female characters who have outlived the digital revolution and will continue to. Characters that live with us and remain faulted heroes. And here’s to the women who made them so electric.

Boyhood is, by logline and poster art, a film about a boy. But I was not alone in walking out of the theater thinking, “Patricia Arquette, you are a baller.” She is undoubtedly the silent hero of the film. From the start, she’s energetic, imperfect, driven, smart (but not genius) and loves her kids even though she wants nothing more from them than to go the hell to bed. She was a single mom who worked hard, got tired, got things moving in her life, and kept on. We’ve seen the foundations of her role a thousand times. (I will hold my comments about any Tyler Perry rendering of real life.) As the film evolved, she made mistakes; her body changed; at times she was involved with her kids and at times she was distant. What to me makes this a successful female role is that if you were to remove the rest of the cast from her, she still has an identity. Motherhood is a part of what she does in the same way that being married or single is a part of what she does. But stripped of supporting cast, she remains a real person with ambitions that grow internally and thoughts that are driven by her own needs and wants.

You see, there was always a storyline that belonged privately to her. She was the master of her own life and the force behind her children’s. When they grew, she grew too. She was very much a mother character AND an individual. It’s roles like these that are needed time and time again in the process of redefining the women we want to see on screen. She is multidimensional and therefore, truthful. (And, yes, I realize the film spans a very real 12 years in the world but even so. ) Kudos to Arquette for rocking the mom jeans like a warrior for 12 years.

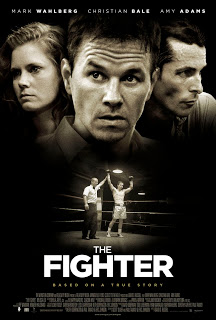

Definitely more overbearing but equally complex was Melissa Leo’s character in The Fighter. She was so nuanced. She got violent, volatile, and was packed with emotion. While she was unpleasant at many points in the story and her motivations were often outwardly selfish, she was honest. It was a straightforward portrayal of a mother not wanting to be outdone, even by her own children. She channels her own life through them and while this may not be a method condoned by any parenting books, she was very much alive and outspoken—faulted and capable of deep love. Again, if robbed of the other characters in the story, she was still a complete human being. There was nothing sexy added to her and yet her ferocious state of mind made her enigmatic and inescapable. (We need not bare tons of boob to get people to watch.) Her dynamic portrayal of a woman in a particular region and socioeconomic position, coupled with the hyper masculine surrounding pulls from her a wealth of complex emotions and decisions. And, let us not forget, unlikeable characters can still serve as outstanding representations of the depth of the female mind, soul, and existence. One of the elements ignored by women’s press this year is crowdpleasing. We want more opportunities. In every way. But I don’t care about crowd-pleasing characters. I go to the movies in search of truth. Give me that.

Taking it even farther into the realm of complex is Julianne Moore in her disturbingly on point performance as Amber Waves in Boogie Nights. Apart from the fact that the movie itself is genius, much of its success is brought out by the powerful performances of its all-star cast. Moore’s character is particularly wild to follow. She has the softness and natural nurturing quality of a mother who has always wanted to be a mother. She is a soothing source of support but this, in the world of Boogie Nights, of course becomes complicated and perverted by the fact that she is also sexually drawn to the very young Mark Wahlberg. Her attraction to him, their on camera sexploits, and her simultaneous motherly qualities make her immediately full of wonder, questions, and provocations.

Adding to that, she’s an exciting hot mess. The woman likes her cocaine as she proves when doing hearty lines with Heather Graham in the bedroom one fateful afternoon. While in this heightened state, if you will, her inner life comes bubbling out and she emotionally confesses about how much she misses her son. She may be all over the place and her nose miiiiight be white at the end of it but she’s given fair treatment by the filmmaker and audience alike. She is trapped by her history, moves in certain ways because of it and, like any fully formed human being, when in a vulnerable position (or totally f***ed up), her inner demons come out into the world. She misses motherhood and longs for her child. It’s a part of her wiring and yet she continues to live outside of it. A hot mess with a real history—it’s a beautiful, vital performance. She embodies multiple elements of a woman in the world in this time and place and she won’t let you look away from it.

Compared to the Hollywood backup female roles we usually passively sit through, not one of these roles and not one of these women has created as a silent, flat, disturbingly calm character. That is an untruthful portrayal in this spectator’s opinion. They came out screaming. Their exuberance breathed into these will written roles the fiery heat of a person with a true life, true purpose and fluid identity. These are the kinds of roles that make more room for women to prove that we thrive in the complex—that we are complex and that we want truth on screen.

Examples of female roles that kick ass exist. Women who will not let their roles become secondary exist. It’s been done since the beginnings of film. Alice Guy Blache’ didn’t take any shit and that was at the turn of the 20th century. She directed, produced and wrote more than 700 films. She was doing it then, and women behind and in front of the camera have done it ever since. It’s our job now, in 2014, to recreate what we can accomplish based on our current industry model and find ways to make sure that truthful performances enter the marketplace. Hollywood films have always had plenty of fluff roles. But they’ve always had standouts. We are still in this position. We have model characters who broke ceilings once before in storytelling and will again. So…carry the torch and rock on.

In case you need further encouragement: Eva Khatchadourian in We Need to Talk About Kevin, Ofelia from Pan’s Labrynth, Kym from Rachel Getting Married, Nina Sayer from Black Swan. Marnie, Briony Tallis, Thelma Dickinson, Kate “Ma” Barker, Marge Gunderson, Bonnie Parker, Shoshanna Dreyfus, Nikita. Judy Barton/Madeleine Elster, Amelie, Evelyn Mulwray, Blanche Dubois, Betty Elms/Diane Selwyn, Coffy, Mia Wallace, Lisbeth Salander, Jackie Brown, The Bride, Hermione Granger, Clementine Kruczynski and Annie Hall.

Like Costner said in The Untouchables, “Let’s take the fight to them, gentlemen.” (ladies)

Mara Gasbarro Tasker is a filmmaker based in Los Angeles. She’s currently working as an Associate Producer at Vice Media and has co-created the Chattanooga Film Festival, launching later this spring. She holds a BFA in Film Production from the University of Colorado at Boulder. She is directing a grindhouse short in April and is still mourning the end of Breaking Bad.