This guest post written by Amy C. Chambers originally appeared at The Science and Entertainment Laboratory and an edited version appears here as part of our theme week on Women Scientists. It is cross-posted with permission.

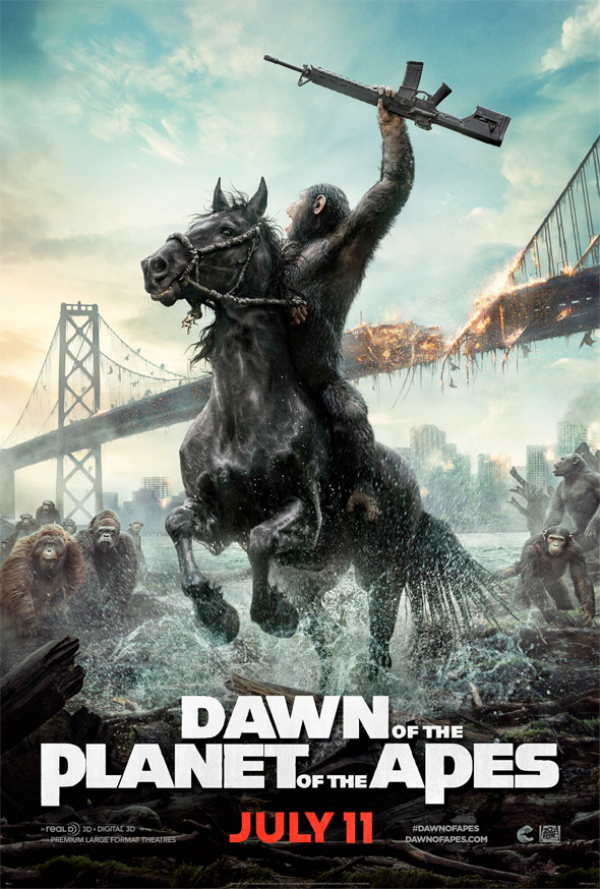

One of my major issues with the most recent addition to the Planet of the Apes franchise, Dawn of the Planets of the Apes (2014), were the roles available to women – both human and ape. In an article I wrote about the film, immediately after its release, I noted that (the very few) female characters were only “represented as child bearers and care takers.” The fabulous Judy Greer, a former dancer who studied simian movement and motion-capture for months in preparation for the role, gets barely any screen-time playing the wife of Caesar (Andy Serkis). Cornelia doesn’t actually get referred to by name so you have to look to the posters or IMDb if you want to know it; interestingly her name is a reference to Cornelius the male chimpanzee from the first three Apes films released in the late-1960s and 1970s (Planet of the Apes, Beneath the Planet of the Apes, and Escape from the Planet of the Apes). The female human, Ellie (Keri Russell) is the only scientist in the film. She is revealed to have worked for the CDC as a research scientist and medic, but in the film she is only given the opportunity to use her medical skills to treat Cornelia’s post-natal complications after she births another boy for Caesar. Ellie’s medical intervention essentially diffuses male aggressiveness and reinforces lazy stereotypes. The women are background characters, barely involved, and overshadowed by their male companions.

I am interested in thinking about how women have been represented in recent Hollywood/American science-based fiction cinema and whether we have really moved beyond relying on stereotypes, sex, and spectacle. Female scientists are increasing in frequency in Hollywood, but they are not being given adequate representation – they are often secondary to their male partners. Any discussion of women in science fiction will often look to the 80s hero, engineer Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) in Alien (1979). Ripley wields her guns, her attitude, and her brains with pride and power, and she blurs the boundaries between feminine and masculine character traits and stereotypes. She has no love interest, she doesn’t need rescuing, and makes better decisions than her male counterparts. She is a young, educated woman, a survivor, and a hero – her gender is not the most important or interesting thing about her. Ripley was originally conceived and scripted as a male character and some of her strength and progressive nature may be attributed to that. But despite the gender-swap history of character, Ripley is still one of the strongest female characters in a science-based movie. I think it is absurd that a character created before I was born is still considered the strongest female character in a science-based movie; it’s 2016, not 1986.

Female scientist characters are often defined by their relationships to men – as a daughter, a girlfriend, a wife, an assistant, or a colleague. Women are rarely presented as having achieved their scientific status and agency without the aid or inspiration of male character. For example, recent blockbuster Interstellar (2014) included two major female scientist characters Dr. Amelia Brand (Anne Hathaway) and ‘Murph’/Murphy Cooper (played as an adult by Jessica Chastain) both of whom are manipulated and inspired by their fathers. Brand is the daughter of the orchestrator of the film’s central mission, Professor Brand played by Michael Caine. But in addition to this relationship, Amelia Brand is willing to sacrifice herself, the mission, and potentially the future of humanity to be reunited with her boyfriend – Dr. Wolf Edmunds. Interstellar’s male lead ‘Coop’/Joseph Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) abandons his daughter Murph and for much of the film she is shown as a woman consumed with anger towards her father. She holds a grudge that spans decades, seemingly unable to appreciate that her father left on a mission to save humanity. Her scientific career and brilliance is apparently driven by her emotion, rather than her own ambition.

I have lots of issues with the Star Trek reboot, and it seems vaguely unfair to pick on just one of them. But let’s talk very briefly about Dr. Carol Marcus (Alice Eve), a Star Fleet Science Officer with a PhD in applied physics and a specialism in advanced weaponry who features in Star Trek Into Darkness (2013). Marcus is ultimately defined by her position as the daughter of Admiral Alexander Marcus – the head of Starfleet. She initially hides her true identity by using her mother’s maiden name: Wallace. Yes, Carol does indeed do some science and saves Kirk, but in one scene this potentially brilliant female scientist is simply, and frankly unnecessarily reduced to a sexual object. It’s a short scene played for laughs, but when one of only two major female characters in a huge science fiction franchise — the other being Zoë Saldana’s Uhura, now in a relationship with Spock — is shown in her underwear (for no reason) you have to wonder about how and why filmmakers incorporate female scientists, and female characters more generally, into their films. This brief sequence feels as similarly out of place as the scene at the end of Alien when Ripley strips down to her underwear. As Xan Brooks comments in an article about Ripley as a revolutionary heroine: “It is as though the makers were so alarmed by what they had unleashed that they tried to rein her back at the last minute.” It was out of place in 1979, and it is unacceptable now.

These are just a few poor examples that caught my eye and they are based upon my own viewing, so I asked my social media hive-mind to help me with producing a list of female scientists in Hollywood films released since 2000. It was not extensive. Interestingly, I could find far more female scientists in films released during the 1990s. We will have missed some, but it should not be that difficult to come up with a list of female characters that took on prominent scientist roles in the last 5, 10, or 15 years.

Excluding Brand and Murph from Interstellar, Carol Marcus from Star Trek Into Darkness, and Ellie from Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, we came up with: evolutionary biology student Karen (Brit Marling) in I Origins (2014), archaeologist and paleontologist Dr. Elizabeth Shaw (Noomi Rapace) in Prometheus (2013); medical engineer Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock) in Gravity (2013), geneticist Dr. Marta Shearing (Rachel Weisz) in Bourne Legacy (2012), astrophysicist Dr. Jane Foster (Natalie Portman in Thor (2011) and Thor: The Dark World (2013), veterinarian Dr. Caroline Aranha (Freida Pinto) in Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011), xenobotanist (studying alien plant life) Dr. Grace Augustine (Sigourney Weaver) in Avatar (2009), genetic engineer Dr. Elsa Cast (Sarah Polley) in Splice (2009), and botanist Corazon (Michelle Yeoh) in Sunshine (2007). Of the women listed here few are, besides Elizabeth Shaw in Prometheus and Ryan Stone in Gravity, their film’s central protagonist. For example, in Rise of the Planet of the Apes, Caroline Aranha is a thinly drawn scientist character and love interest who assists Will Rodman (James Franco), and in Bourne Legacy, Marta Shearing is a brilliant but dangerous geneticist working in a secret lab who becomes a love interest and damsel in need of rescue for/by Aron Cross (Jeremy Renner).

In Thor (2011), Jane Foster is an astrophysicist rather than a nurse, as she appeared in Marvel’s Thor comics. She is apparently given an intellectual upgrade and a sassy non-scientist female intern named Darcy (Kat Dennings). Jane was changed from a nurse to a research scientist following discussions between science advisors provided by the Science and Entertainment Exchange and the filmmakers, who wanted to update the character for a 21st-Century audience. Portman prepared for the role by reading the biographies of women scientists and was interested in creating a female scientist that could extend beyond the clichés of what a female character could be and do.

“I got to read all of these biographies of female scientists like Rosalind Franklin who actually discovered the DNA double helix but didn’t get the credit for it, the struggles they had and the way that they thought — I was like, ‘What a great opportunity, in a very big movie that is going to be seen by a lot of people, to have a woman as a scientist.’ [Jane]’s a very serious scientist. Because in the comic she’s a nurse and now they made her an astrophysicist. Really, I know it sounds silly, but it is those little things that makes girls think it’s possible. It doesn’t give them a [role] model of ‘Oh, I just have to dress cute in movies.” – Natalie Portman

The decision to make Jane Foster an astrophysicist was motivated by a desire to incorporate references to ‘real’ science and to incorporate a female scientist who might act as inspiration for future female scientists. It is indeed great to see a major female character in a blockbuster movie franchise as a scientist. But in the presence of Thor (Chris Hemsworth), Jane just goes googly-eyed and her scientific career and research become secondary to this new love interest (who just happens to literally be a god). She accepts his framing of science as magic without questioning (as any leading scientist would) and her research seems to ultimately become about finding him after the Bifröst Bridge is destroyed at the end of the first movie. In a great scene from Thor: The Dark World (2013), Jane is on an awkward blind date that she cuts short when Darcy crashes the date with new findings and readings that had previously preceded the arrival of Thor. Jane was framed as “the woman of science” in the film’s 2010/2011 marketing campaign, but in the film itself, her scientific prowess has NO influence upon the plot. Jane’s advanced understanding of astrophysics and her research is seriously under-used and so is the character who given little chance to develop beyond being Thor’s human love interest.

For a genre that is defined by its futuristic otherworldly framework and its potential to imagine alternate societies and power relations, the cultural politics of the science fiction genre have been consistently Earthbound. Movies reflect the period in which they are created and they often present both hopes for progress as well as revealing deep-seated prejudices. Filmmakers often fail to fully realize their attempts at progress – although this can be due to a number of reasons across the production process, including interference from the studio, and in the reception of the film that is outside of the director’s control. As feminist science fiction writer and critic Joanna Russ famously noted, science fiction narratives present a type of “intergalactic suburbia,” where Western society is presented with only a few futuristic additions, tending towards showing “an idealized and simplified” past that retains traditional power relations. The world has undergone huge advances across STEM but traditional, binaristic gender relations remain in tact. Russ’s comments criticize not only gender representation but also race and class by recognizing the preservation of traditional structures in futuristic and near-future narratives.

Is it possible to change perceptions of women in STEM through better and more pervasive representation of women in science-based popular cinema? Would more female scientists in popular cinema help to encourage young women to pursue STEM careers? Several groups are working to improve the representation of science, and women of science in the film industry. For example, The Science Entertainment Exchange “is a program of the National Academy of Sciences that connects entertainment industry professionals with top scientists and engineers to create a synergy between accurate science and engaging storylines in both film and TV.” They work to create a stronger relationship between the industry and experts in order to present a more realistic image of science and scientists, both women and men, on-screen. The Scirens promote the need for increased science literacy in the general public and consider how women can be ambassadors for this cause. One of the Scirens, Taryn O’Neill, wrote an interesting piece on this subject called “Actresses for STEM“ that inspired the project; it is worth a read. They have all worked to improve representation by encouraging a movement away from clichés in order to engage and retain audiences.

A study published in 2005 by Jocelyn Steinke looked at female scientist representation between 1991 and 2001. She found that about 30% of scientists in the movies released in her survey time-frame were female and that those women tended to be sane, eschewing the “mad evil scientist” stereotype, and tended to avoid questionable scientific experiments. Although in more recent cinema, Elsa in Splice and Marta in Bourne Legacy do use science in an ethically problematic fashion, with Elsa splicing together the DNA of different animals to create new hybrids for medical use, and Marta experimenting upon and maintaining genetically altered super assassins. Despite these two recent examples, women scientists on-screen are generally positive figures. At least until you consider how restrictively they are packaged – as Eva Flicker notes in her Public Understanding of Science article “Between Brains and Breasts“:

“[The female scientist] is remarkably beautiful and, compared with her qualifications, unbelievably young. She has a model’s body – thin, athletic, perfect – is dressed provocatively and is sometimes ‘distorted’ by wearing glasses.”

An interesting example of this from recent TV is computer scientist Felicity Smoak in Arrow (2012-) – she wears glasses in the lab and removes them when she goes undercover as ‘the beautiful woman’ allowing her to slip into venues unnoticed. She’s more than just a bit of sci-candy as her abilities are integral to the mixed gender team she works with, but it is intriguing that she still falls into a visual classification that can be applied to the representation of female scientists since the 1930s. Although arguably, female scientists and highly-intelligent female characters should be allowed to be both beautiful and brainy, shifting away from the idea that beauty and brains are mutually exclusive, Hollywood is still offering a restricted image of the gifted woman. Science can be as the European Commission recently campaigned ‘a girl thing!’ – but there must be scope to communicate the notion that science is for everyone regardless of gender, race, sexual orientation, age, disability, or class (Alice Bell wrote a brilliant response to the European Commission campaign).

Some major future-dystopia film franchises have shown the potential for multifaceted female characters. The Hunger Games and Divergent do provide smart female protagonists: Katniss Everdeen (Jennifer Lawrence) and Tris (Shalene Woodley). But these women are fighters and leaders, not women of STEM. Both of these franchises are based upon young adult (YA) novels and therefore do not necessarily work well as comparisons to the adult science-based narratives I have been discussing. The rules are different for YA adaptations; since the immense success of The Twilight Saga teenage girls have become a major market for Hollywood and films are made to specifically cater for this influential and profitable group. The problem seems to be adult women. The idea that women, and perhaps even some men, might want to see a film with a female lead and a cast with more than a few token women is seeming incomprehensible for contemporary Hollywood. The desire for big opening weekends and early high profits has possibly created a culture of stereotypical gender representation, and a tired narrative cinema that relies upon reboots, sequels, and reaffirming traditional structures. Rise of the women? Not really.

See also at Bitch Flicks: Women in Science in the Marvel Cinematic Universe; The Women of ‘Interstellar’; ‘Dawn of the Planet of the Apes’: My Dear Forgotten Cornelia; Does Uhura’s Empowerment Negate Sexism in ‘Star Trek Into Darkness’?; Did Gender Alter the Tone of the ‘Alien’ Series?; The Women of ‘Thor: The Dark World’; ‘Star Trek Into Darkness’: Where Are the Women?

Amy C. Chambers is a postdoctoral researcher at Newcastle University in the UK researching the intersection of science and entertainment media. Her newest project explores the representation and the projected futures of women within scientific cultures in science fiction. She blogs about her research and interests at the Science and Entertainment Laboratory and The Unsettling Scientific Stories Project, and you can follow her on Twitter at @AmyCChambers.