This guest post by Emanuela Betti appears as part of our theme week on Unlikable Women.

Hollywood has produced some of the most memorable bad girls and wicked women on-screen—from silent era’s infamous vamps to film noir’s femme fatales—but bad women do more than just entertain, particularly if we’re talking about the sweepingly emotional and excessively dramatic world of woman’s melodrama. The bad girls I will be discussing are different from the exotic vamps of the ‘20s and the dark femme fatales of film noir; while both these types have their own essence of “badness,” it’s the women in melodramas, specifically the woman’s film sub-genre from the 1930s through the 1950s, where you’ll find some of most unapologetic bad girls in cinema.

I will first explain why the vamp and film noir’s femme fatale are not as interesting, or at least not as groundbreaking compared to the bad woman in woman’s film. Although I’m personally fascinated by both archetypes, the vamp and femme fatale are “creatures of prey,” and that prey is always and inevitably a man. The femme fatale is in essence a selfish creature (this is most evident in the vamp, short for “vampire”) and their function is to extract every penny or remnants of a soul from the male character; in short, the purpose of the femme fatale is to cause a man’s downfall. Nothing wrong with that—but in this perspective, these female archetypes can hardly exist if not in relation to, or in the context of, a male-dominated world.

The femme fatale also exists in the woman’s film, but due to the nature of the genre, the archetype is in a very different position. The woman’s film is a sub-genre of the melodrama, and is strictly centered around women. The genre takes place within a woman’s world, and the bad woman exists in relation to other women. A common trope is the “double woman,” which manifest as a look-alike or as a sister/twin: a good example are the twins in A Stolen Life or The Dark Mirror. Whether they’re rivals or friends, sisters or twins, the trope of the “double woman” implies that femininity is split into two sides, and the bad woman embodies the negative side of that spectrum.

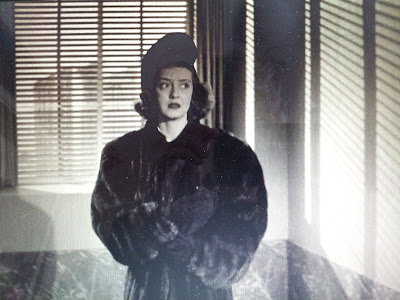

While film noir tells us that women are dangerous flytraps, the woman’s films give us insight into how Hollywood spoke to women. Specifically in the case of “double woman” films, in which we are presented with a good character and a bad character, the good one always prevailed. Evil or fallen women were not permitted to win, and by the movie’s end, they were subjected to punishment either through death or abandonment. The woman’s film was a genre that allowed female spectators to live vicariously through a bad woman—Bette Davis, Gene Tierney—but by the end, female audiences were taught that being bad doesn’t pay. The path of the good woman was the most prosperous, and only those who submit and surrender get the man. Basically, the “negative” side of femininity was associated with women who did not submit or conform, and Hollywood eagerly discouraged any identification with them.

I am always disappointed and sad when the bad woman, who I usually root for, is finally subdued or destroyed. Yet, the act of being punished brings up a lot of questions: why is she punished, and what for? Not all bad women were murderers, criminals—and most often, they’re biggest fault was just stubbornness.

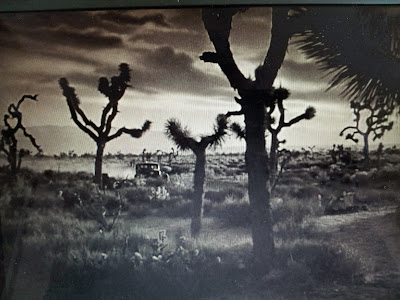

Jeanine Basinger describes woman’s films as a genre of limitations: the typical environments that these women inhabit are department stores, prisons, but most often these films take place in the home. Although the women may inhabit a woman’s world, they were restricted on every side. Their personality, their environment, and their success are all dictated by a male-governed ideology: women’s place is in the home, and their only career is love and marriage. The bad woman breaks out of these imposed limit: Gene Tierney in Leave Her to Heaven plays Ellen Berent—a sporty, outdoors type—completely defying the convention of a woman relegated to a domestic setting; Dorothy Malone plays Marylee, a promiscuous heiress in Douglas Sirk’s Written on the Wind, dressed in hot pink and flirting with the confidence of a playboy. These characters are punished because according to a male-governed system they go against what is deemed “acceptable” in a woman: they’re aggressive, stubborn, and active (compared to the good girls—Ellen’s sister, Marylee’s romantic rival—who are passive, submissive, and compliant).

Another important aspect of these bad women is the fact that men cannot understand them, which makes them harder to pin down and subdue. It’s not uncommon to see the inclusion of psychoanalysis in woman’s films, with characters described as “mad” or “hysterical.” To pin down unexplainable behavior is an attempt to subdue and control it: we see this in Leave Her to Heaven, in which Ellen’s doctor attempts to understand her lack of maternal instincts; in Cat People, Irena’s aggressive sexuality is described as a supernatural occurrence. The medical gaze, in which a doctor attempts to ascribe a woman’s bad or unusual behavior as a result of mental illness, is very close to the idea of the male gaze. When a woman defies the male gaze, the medical gaze may attempt to explain and understand her, in an effort to “fix” her. As much as on-screen psychiatrists and analysts try to “help” the women, they always seem to fail, never able to pin-point why a woman would want to live outside a male-dominated system. So wanting to go horseback riding instead of cooking dinner meant the woman was evil. But was she, really? Or maybe she was just a woman who somehow managed to dodge every attempt at being domesticated.

Finally, bad girls in woman’s film are similar to femme fatales in some ways: they enjoy men, want men—but don’t really need men. Men often play marginal roles in the woman’s film, usually a romantic interest who is too often overwhelmed by the women’s personalities, and often fail to control the woman. In Jezebel, Bette Davis calls off her engagement numerous time, and always due to the fact that she’s too stubborn to submit to her fiancé’s idea of an “acceptable” idea of femininity. Jezebel, and Ellen, and Marylee are full-flesh women, and their existence is not defined by men—instead, their biggest conflict lies between maintaining their identity or giving it up for their man.

The “bad girl” in woman’s film is not so much a wicked or evil person, but simply a woman who unapologetically inhabits her world, and the belief that she is ruler of that world is her biggest crime. In the end, her defeat is really a victory: she cannot exist in a world in which the rules are set by men. Her final demise leaves the men bitter, because they could never control the bad woman, and she never gave them the chance.

Emanuela Betti is a part-time writer, occasional astrologer, neurotic pessimist by day and ball-breaking feminist by night. She miraculously graduated with a BA in English and Creative Writing, and writes about music and movies on her blog.