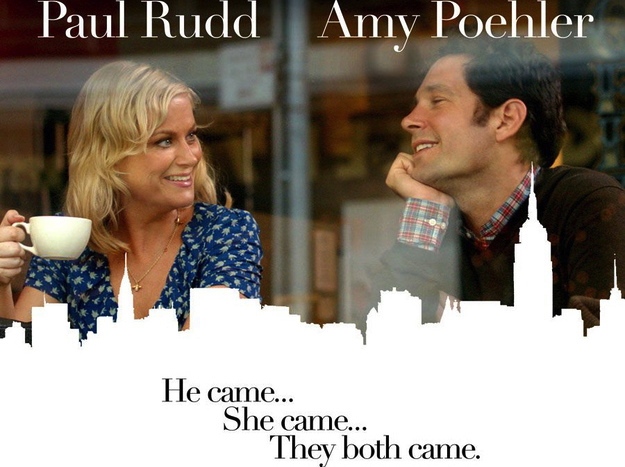

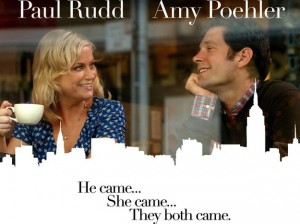

It’s easy to look at the ads for They Came Together and expect a straight romcom. The poster and the film are glossy and full of comedic stars. New York is so important to the story it’s like another character. The leads, Amy Poehler and Paul Rudd as Molly and Joel, play exaggerations of the roles they could be cast in in any other film. She’s the big-hearted and dangerously clumsy proprietor of a quirky little candy shop that gives all its proceeds to charity, while he’s a big candy executive who dreams of a simpler life, obsesses over sex, and threatens to shut down Molly’s shop. They get together.

That much is obvious once you hear it’s a romantic comedy.

They Came Together, the latest from David Wain and Michael Showalter, the team behind cult pic Wet Hot American Summer, intends to parody these easy conventions, and though an enjoyable film, it’s debatable what it actually accomplishes. Comedy is a difficult matter to critique as so much of what we find humorous is specific to us as individuals, as well as to factors like our culture, class, and age, that it’s nearly impossible for one person to stand up on a soapbox and declare whether or not something is funny. Adding to that, They Came Together is a polarizing film by nature. Its humor is absurdist and jokes zig and zag completely out of left field, sometimes feeling more like an extended sketch than a feature film. There are subtle visual gags, highly telegraphed centerpiece jokes, clever observations about life both in the real world and in the sunny world of the romantic comedy, plenty of raunch and some of those repetition bits that run just long enough to stop being funny and then to get funny again, thrown in for good measure. In short, it’s a comedy grab bag for which both rants and raves are justified.

Much of the romcom references are bang on. The basic plot, cribbed from You’ve Got Mail, pegs an uptight man against a free-spirited woman and tells us he needs her to help him believe in his dreams, while she needs him to help her become more grounded. To stress this point, they’re even given wrong partners as contrast, ever-literal accountant Eggbert (Ed Helms) and perfectly put together Tiffany (Cobie Smulders). All the genre staples we know and are growing tired of are there: Joel gets advice from basketball playing pals who each represent a different point of view (and tell us out-right which idea they represent), they bond over their “quirky” shared tastes, in this case a love of fiction books and a hatred for the complications of modern life, spread their clothes all over Molly’s apartment while making out and fall in love through a montage that shows them buying fruit and playing in fallen leaves.

There are also some new and intriguing points made by the film about how race and class are portrayed in earnest examples of the genre. For existence, Molly’s assistant is Black woman who appears to have no life other than helping her, even picking up the phone in one scene and assuming the call is for Molly before even asking. Later into the film, it is revealed that Molly has a young son, and has such an easy time being a single mother that his presence in her life wasn’t even noticeable until it was pointed out. The movie fantasy of easy success and money is also briefly deconstructed in the end, when the main character’s business fails and cannot be salvaged.

With the film’s absurdist style, the plot and characters can’t really be dissected at length. But a romcom parody is particularly interesting for its power to point out annoying or offensive staples of the genre, in particular, their portrayals of women. Though a genre geared toward women, female characters in romantic comedies are uniformly portrayed as cardboard cut-outs, needy bleeding hearts or catty and conniving villains. In They Came Together, the one-dimensional nature of the female characters is pointed out as part of the joke. Molly’s business is failing because of her compulsion to give candy away and she never once thinks of changing the way she runs things. Likewise, Tiffany tells Joel point-blank that she is untrustworthy. In contrast, Joel is a complicated character who supports his younger brother, is conflicted about his job, and has strange feelings for his grandmother.

The difference between men and women is also boiled down to one point, that men are easy-going and order from the menu, while women are needlessly complicated (like Meg Ryan in When Harry Met Sally) and have impossible specifications for how their food must be prepared. This idea, a common one in romantic comedies that has even bleed into real life expectations, is clearly posed as ridiculous.

But one target the film should have paid more attention to is the derision of the romantic comedy genre without our collective culture. When a new romcom opens, most of us expect it to be terrible, sight unseen. Horror films, another genre that can be cheaply and quickly made, don’t suffer the same derision, perhaps because the genre is generally geared toward a masculine audience. While bad horror is recognized as such, masters like John Carpenter and Wes Craven are still routinely praised, even by film buffs who are not major fans of the horror genre. Meanwhile, giants of romcoms like the late Nora Ephron, are seen as bi-words for schmaltzy “chick” movies no serious person would admit to liking. In my own life, I can’t recall the last time I heard a woman admit to a fondness for the likes of Sleepless in Seattle or Never Been Kissed without adding “as a guilty pleasure” in a knee-jerk reaction.

That was a big part of the wild success of Bridesmaids and its reputation as a game-changer: while a lot of the story presented wasn’t new, it was the first romantic comedy in a long time that we were “allowed” to like as something more than the garbage film meant for watching alone in sweatpants while nursing a carton of Hagen Daas.

Somehow it got drummed into our heads that the romantic comedy isn’t meant for us.

I’m making some wild generalizations about you as a reader here, but I’m going to guess that you’re something like me. You consider yourself smart, cynical and wary of the phase, “Well if you didn’t like it, that means you didn’t get it.” I’m not generally a fan of romcoms, but I’m starting to wonder how much of that distaste comes from the idea that they’re not “serious movies,” that they’re not worth my time, that I’m not supposed to like them. Sure, I’m turned off by the cutesy modern touches like klutzy women, quirky businesses, the plague of architect love interests (one trope missing from They Came Together) and honestly by the term “romcom” itself, but none of those things are that tied up in my ideas of modern womanhood and my comportment. I roll my eyes at them and I’m over it.

A romantic comedy where characters always succeed regardless of business sense or marketability and end up up happily ever after, is like a fairy tale to me; I don’t feel held to the expectations of women presented in them. But what I do feel constrained by is the idea of a universal taste, the final opinions formed in almost unspoken consensus that this show is a masterpiece or this show is crap, wherein anyone who disagrees loses all credibility.

Genres that cater to women are already disadvantaged in this respect as they’re seen as veering away from the universal, generally masculine path of canonized media. No matter how much important journalism or honest snapshots of our lives women’s magazines present, they’re still seen as trash. Female bloggers that write in a colloquial style that mirrors their style of speech and engages with their female readers are seen as unserious and dumb. Likewise, Girls was only acceptable as a good show after it gained the approval of young male viewers and with the approval of bro-humorist Judd Apatow.

There’s joke I’ve heard a lot recently: “I’m not like most girls”- most girls.

For most young educated women, romantic comedies are for those others, the stereotypical girl we imagine existing somewhere (basically characters played by Mindy Kaling), the one we’re deathly afraid of appearing be. We claim not to diet, we have female friends, we would never force a date to see the latest Jen Aniston movie, we call ourselves low maintenance. Sure, we want someone to love but we don’t see it as the ultimate goal in life.

But in truth? I’m sure we’ve all got “girly” things we truly love that compromise a good portion of identity. And it shouldn’t be shameful to like things that are supposed to be for women, just like shouldn’t be shameful to reject them or to like media geared toward both masculine and feminine audiences.

It’s probably taking things too far to say I hope They Came Together will change filmmaking or consumption; it’s a light comedic parody without activist intentions. Still, it’s the kind of film that, intentionally or not, makes you think about what we’re used to seeing on the screen and wonder why we have accepted certain ideas presented to us without complaint. Like why is one genre for women and another for men/everyone?

It hasn’t always been this way. Past romantic comedies from the 30s, even through the 90s where much of the tropes in They Came Together originated from, have been acclaimed as serious films, targeted to a universal audience and even Academy Award-ed. Many of these films were even posed from a masculine point of view, following a male character’s quest for love instead of a woman’s.

Sure They Came Together is parody, but despite its basic romantic comedy structure, it’s aimed at any audience appreciative of its brand of comedy and assumes even male viewers are familiar with the genre. Is it hopelessly naive to wish that the very existence of this film, which takes for granted that the audience will recognize romantic comedy tropes and see them as stale, will lead to some innovations?

See Also: The Romantic Comedy is Dead

________________________________________________________________________

Elizabeth Kiy is a Canadian writer and freelance journalist living in Toronto, Ontario.