Spoilers ahead!

As White Bird in a Blizzard opens, Kat Connors (Shailene Woodley) is a teenage girl like any other, just at that point where she’s realizing how the life she wants for herself differs from the one modeled by the adults around her.

It’s 1988 and she’s challenging the limits for what she get away with, stomping out of her suburban home in heavy make-up and short skirts, enjoying loud music and lots of sex, and through all of it, fighting with her disdainful housewife-in-pearls mother, Eve (Eva Green, popping in to play a variation of the cold, elegant woman role she’s perfected).

As she matures, Kat begins to see the cracks in her parents’ 1950s style-American Dream-marriage. Her nebbish father Brock (Christopher Meloni) is flailing in his attempts to understand Eve, who is displaying depressive symptoms and acting jealous and even cruel toward Kat.

For months, Kat idly notes Eve’s increasingly odd behaviour, but is too busy falling in love and losing her virginity to care, until, suddenly, one day, Eve disappears without a trace. Kat assumes she ran away because she didn’t love them, and attempts to go on with her life, but a police investigation slowly begins circling her family.

As an audience, we’ve been conditioned to see a movie with thriller or mystery elements in it as a thriller or mystery story. But Gregg Araki’s film, White Bird in a Blizzard, is only part mystery, part coming of age story, and part haunted dreamscape, and refuses to be easily categorized as any of the above. The atmosphere, steamed up with Kat’s barely contained lust and Eve’s frosty shadow, dominates.

The real mystery is not who killed Eve or where she disappeared to. In fact, these answers are hinted at early on and are clear to the audience long before Kat even cares to investigate for herself. If a mystery is at important, it’s the mystery of what kind of person Kat will end up being and how her memories of her difficult, often unlovable mother, will shape her in her adulthood.

The film follow Kat through two years pivotal years, as she finishes high school and begins college, punctuated with voiceover narration, flashbacks to her earlier relationship with her mother and introspection delivered in appointments with her psychiatrist. For most of this time, Kat is unmotivated to solve the mystery and this plot is sidelined by her burgeoning sexuality.

Things drag a bit in this section, as the film becomes merely a teenager’s sexual odyssey with hints of something darker just offscreen, just outside of her experience. We watch Kat get tired of her dumb and shiny first boyfriend, Phil, the boy next door (Shiloh Fernandez), and move on to the macho cop in charge of her mother’s case (Thomas Jane). Kat is unapologetically sexual. She admits that she is “horny” and excited to have sex again and again, complaining to Phil that it has been too long since they’d last done it. For Kat, this was not true love and she knows it. Her desire is sex itself, not sex with him specifically. In her conscious attempt to seduce of the detective, assuring him she is already 18 and already sexuality active, she is not a lost little girl manipulated by an older man, attempting to use this relationship to make an official move into adulthood. However, besides sex, there is little at stake until the final act.

Kat enjoys sex and admires her body, rare things for a teenage girl to be allowed in either movies or in real life. She has reason to be proud, as she has carved and shaped out her body, from beneath the prepubescent baby fat her mother always teased her about. Eve was the kind of mother who tsk-ed at every bite her daughter took, constantly reminding her of how much thinner and more appealing she was at her age. But as Kat relates, her mother only became crueler toward her as she came into her own.

Their dynamic is a Grimm’s fairy tale, the beautiful daughter sucking the life out of her once beautiful mother, slowly killing her and then replacing her as an object of lust. In Eve’s mind, they appear to be in competition. After noticing Kat’s new body, she appears in revealing clothes in front of Phil and flirts with him. She watches Kat dress and do her make-up, hidden in the shadows, and lingers too long to watch her fooling around with Phil. In one harrowing scene, she comes into Kat’s room at night and attempts to physically assault her.

One possible flaw in the otherwise skilled depiction of their difficult relationship is the casting of Eva Green as the mother of Shailene Woodley’s character when she is only 12 years older than her. By casting an actress who is not old enough to be Kat’s mother, the idea of the sexual identity crisis and aging Eve is experiencing is skewed. This is not how she should look at this age, because the actress is not of the right age.

The disappearance of Kat’s mother echoes the conflict between a mother and her daughter as she comes of age. Kat must reject her mother’s influence and ideals in favor of forming her own. Here, Kat’s mother services as a destructive influence on her life, but this influence is pervasive and unshakeable. Kat cannot reject her mother, even when she is sure her mother has rejected her, even that her mother never loved her. Even as she tries to, Eve haunts her memories and she has recurring dream of her naked in the snow and calling out for her.

Because of their troubled relationship, Kat feels little pain or sadness at her mother’s disappearance. She blames all her and her father’s unhappiness on Eve and encourages him to move on and find a woman who deserves him.

Still, the film resists the temptation to make Eve into a monster. Though Kat struggles to find something redeemable about her mother, some humanity in her that she can love, she never doubts Eve’s essential humanity and that the rational behind her actions. Kat speaks of Eve’s history like a biographer, dissecting her thoughts and motives as if she was there to hear them

As viewers used to suspense plots, we expect from the beginning that something sinister has happened to Eve. With this in mind, Kat’s attempts to reconstruct her mother are shadowed by our idea of Eve as a victim.

This presents a challenge to viewers: Can Eve be both villain and victim? And which is a crueler – the physical violence visited on Eve or the psychological destruction Eve imposes on her daughter?

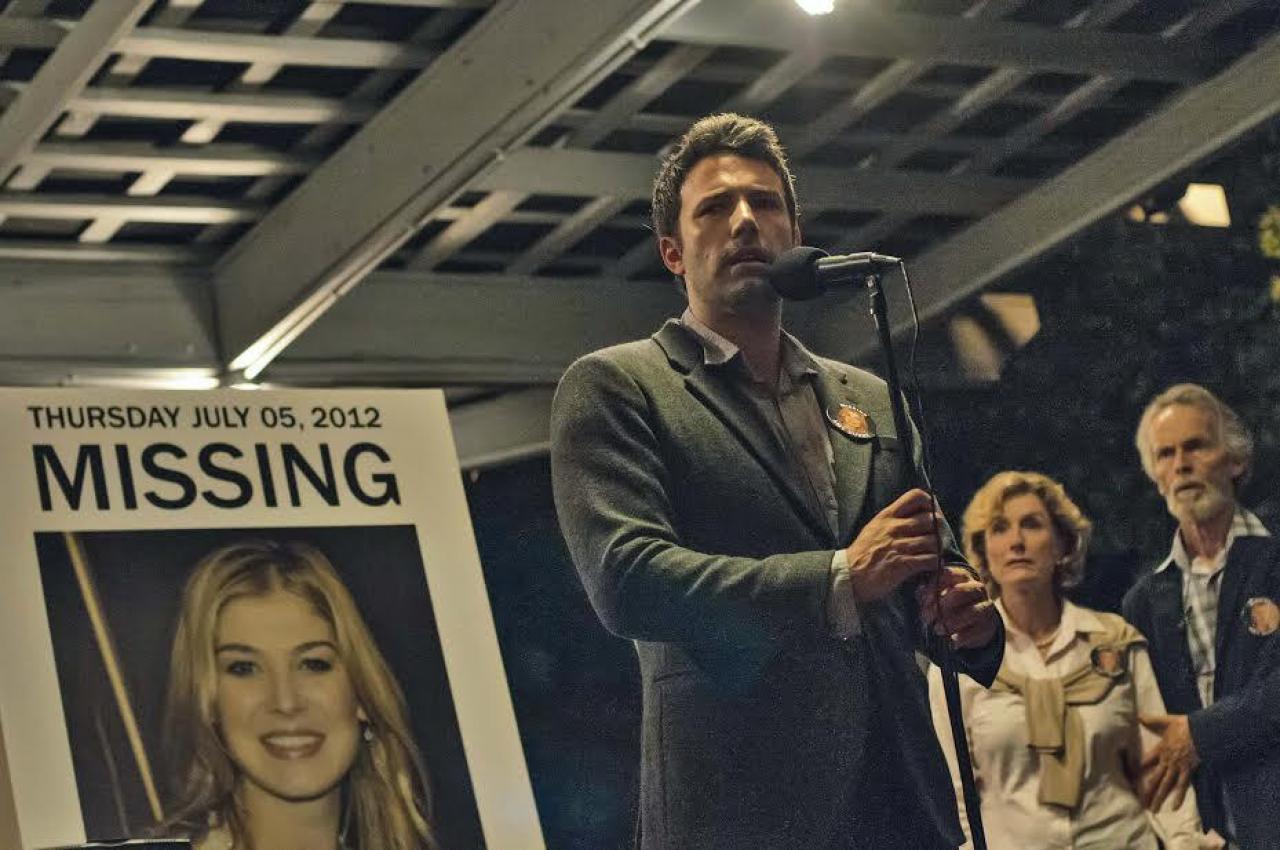

From Kat’s narration, the viewer is compelled to sympathize for Brock and share her hatred of Eve, a strange position for the narrative as it becomes clear to the viewer that Brock had a hand in Eve’s disappearance. The eventual reveal, that Brock murdered Eve, is not subtle, as viewers we expect this, as we are used to stories where the good-guy husband is revealed to be a killer. Kat, from her biased perceptive as his child, perhaps willfully blind to his true character, is more naive than us as an audience and than other characters.

In fact, every one around her, from her cop boyfriend to her two friends, tell her father has long been the chief suspect in Eve’s disappearance. At this point, it has never been in the least implied by Kat’s narration, by the story steered by her point of view. We never see hints of her father’s jealousy or his fits of rage, which Kat is told until the last act, instead we make these realizations along with her. For most of the film, Brock seems like a harmless milquetoast harangued by his dissatisfied wife. This is the view Kat uses to introduce us to her father and to contextualize her parents’ relationship, thus it catches the viewer off guard, and even scares us, when he reveals hidden stores of anger and turns them on his daughter, his long-time supporter

Though the voiceover is relayed in Woodley’s voice with infrequent teenager vernacular, Kat’s view on the events, is cold and distanced, full of beautiful prose (most straight from Laura Kasischke’s source novel) and bloodless dissection of her mother’s motives. The wounds of her mother’s disappearance and her complicated adolescence do not seem at all fresh (note that Kat begins her narration with a suggestion of time passing, “I was 17 when my mother disappeared”). Her narration is composed, even going as far to recall her mother’s prim, patrician energy. The blossoming girl Kat has become a jaded woman, still fighting to care about her mother.

Yet, she seems unaware of events until there are revealed and gives no foreshadowing of Eve’s eventual fate. Eve is posed as the villain and Brock is the victim, even though Kat should know how these roles are reversed. While she struggles to see her mother as sympathetic, she seems to make no effort to rectify the two sides of her father.

The real surprise of the film is the ending twist, which is the sort of twist that seems calculated to give viewers something to talk about as they leave the theater. Instead of revealing that Brock discovered Eve was sleeping with Phil and killed her out of jealousy, as most of the film seemed to imply (and is the ending of the book the film is based on), Eve discovers Brock was sleeping with Phil and he explodes in rage when she laughs at him.

If you believe in auteur theory, this is a clear example of director Araki putting his own stamp on the material, as he is primarily known for the Queer themes of his films. Though a unique twist, this ending feels tacked on for shock value, rather than organic to material. There are no hints at this twist to look back on, and in fact it seems as if it was just made up on the spot after the rest of the film was shot with the original ending in mind. Much of Eva Green’s performance and the importance of her dynamic with Kat no longer make sense in light of this ending.

Still, as a coming of age film, White Bird in a Blizzard is a success at depicting Kat as a real teenage girl, hovering in that confusing stage of adolescence where she is neither fully grown up but is certainly not a child. It is a quiet, often very beautiful film about growing up and coming to terms with the sins of your parents, figuring out how you will use their lessons and to form your own identity. In the end, Kat has lost both her parents and has reasons to hate both of them, yet she still has to live in the world and try to figure out how she can understand who they were and what they made her.

_______________________________________________________________________________________-

Elizabeth Kiy is a Canadian writer and journalist living in Toronto, Ontario.