This post by Jenny Lapekas appears as part of our theme week on Female Friendship.

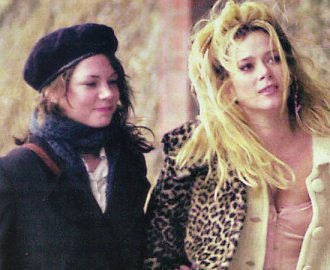

In the spirit of Boys on the Side, along with a dose of teen angst, Foxfire is perhaps the most bad ass chick flick ever. Many Angelina Jolie fans are not aware of this 1996 phenomenon, where Angie makes a name for herself as a rebellious free spirit who changes the lives of four young women in New York. Based on the Joyce Carol Oates novel by the same name, Foxfire is the epitome of girl power and female friendship, a pleasant departure from the competition and spitefulness often portrayed between women characters on the big screen (see Bride Wars and Just Go with It). However, it does seem that Hollywood is catching on as of late, and producing films that cater to a more progressive viewership (see Bridesmaids and The Other Woman). When I first saw Foxfire around 16 years old, I stole the VHS copy from the video store where I worked at the time.

Angelina Jolie’s shaggy hair and tomboy style in the film, along with her portrayal of the rebellious Legs Sadovsky, play with gender expectations, challenging our assumptions pertaining to clothing, gait, etc. Legs’ biker boots and leather jacket highlight the general heteronormative tendency to find discomfort in these roles and depictions. An androgynous drifter, Legs oozes sex appeal and promotes the questioning of authority. She teaches the girls to own their happiness, to correct the injustices they encounter, and to assert themselves to the men who think themselves superior to women. Legs’ appearance in Foxfire is paramount; she’s even mistaken for a boy when she breaks into the local high school. A security guard yells, “Young man, stop when I’m talking to you.” We see this confusion repeat itself when Goldie’s mother tells her daughter, “There’s a girl…or whatever…here to see you.”

The film’s subplot involves a romance of sorts between artist Maddy and Legs, the mysterious stranger, while Maddy feels a large distance growing between her and her boyfriend (a young Peter Facinelli from the Twilight saga). The intensity of the “girl-crush” shared between Maddy and Legs is akin to that of Thelma and Louise; while we come to understand that Legs is gay, Maddy’s platonic love is enough for the troubled runaway. Legs also assures Maddy after sleeping on her floor one rainy night, “Don’t worry, you’re not my type.” Similar to my discussion of the reunion between Miranda and Steve in Sex and the City: the Movie, the two young women coming together on a bridge is heavy with symbolism, especially when Legs climbs to the top and dances while Maddy looks on in horror and professes that she’s afraid of heights: a nice precursor for the unfolding narrative, which centers on Legs guiding the girls and easing their fears, especially those associated with female adolescence and gaining new insight into their surroundings and how they fit into their environment.

In a somber and almost zen-like scene involving Maddy and Legs, they profess their love for one another outside the abandoned home the gang has claimed as their own. Maddy says, “If I told you I loved you, would you take it the wrong way?” Obviously, while Maddy doesn’t want Legs to think she’s in love with her, she wants to make clear that the two have bonded for life and are now inextricably linked in sisterhood. Maddy indirectly asks if Legs would take her with when she decides to move on, and Legs hints that Maddy may not be prepared for her nomadic lifestyle. The platonic romance shared by both young women culminates in tears and heartache when Legs must inevitably leave.

Legs is the glue that binds these young women, and she literally appears from nowhere. Her entrances are consistently memorable: she initially meets Maddy as she’s trespassing on school property, she climbs to Maddy’s window asking for refuge from the rain (another Romeo and Juliet moment), and eventually takes off for nowhere, leaving the girls stupefied and yet more lucid than ever. Legs is something that happens to these girls, a force of nature, a breath of fresh air. When she tells Maddy that she was thrown out of her old school “for thinking for herself,” we can safely assume it was just that–refusing to conform to the standards of others. The unlikely friendship that forms amongst this diverse group of girls clarifies the idea that this gang dynamic has found them, not the other way around; the pressed need for the collective feminine is what brings the girls together, rather than some vendetta against men.

Legs sports a tattoo that reads “Audrey”: her mother, who was killed in a drunk driving accident, and we clearly see in the film’s final scenes that Legs suffers from some serious daddy issues, when she angrily announces that “fathers mean nothing.” Delving briefly into Legs’ painful past, we discover that she never knew her father. The quickly maturing Rita explains to Legs, “This isn’t about you.” Each of the girls has their own set of issues within the film: Rita is being sexually molested by her scumbag biology teacher, Mr. Buttinger, Goldie is a drug addict whose father beats her, Violet is dubbed a “slut,” by the school’s stuck-up cheerleaders, and Maddy struggles to balance school, her photography, and her boyfriend, who is dumbfounded by Legs’ influence on his typically well-behaved girlfriend.

In an especially significant scene, the football players from school who continually harass the girls attempt to abduct Maddy by forcing her into a van. The confrontations between the groups progressively escalate throughout the movie, and climax after Coach Buttinger is apparently fired for sexually harassing several female students. Legs shows up donning a switchblade and orders the boys to let her friend go. Of course, the pair steal the van and pick up their girlfriends on a high speed cruise to nowhere, which ends in an exciting police chase and Legs losing control and crashing, a metaphor for the gang’s imminent downfall. The threat of sexual assault dissolved by a female ally, followed by police pursuit and a car crash has a lovely Thelma & Louise quality, as well. The motivation here is to avoid being swept up in a misogynistic culture of victim-blaming. What’s interesting about this scene is that another girl from school, who’s in cahoots with these sleazy guys, actually lures Maddy to the waiting group of boys, knowing what’s to come. Meanwhile, Maddy tells Cyndi that she’d escort any girl somewhere who doesn’t feel safe, highlighting the betrayal at work here. Cyndi, the outsider, exploits Maddy’s feminist sensibilities, her unspoken drive for female solidarity and the resistance of male violence to fulfill a violent, misogynist agenda and put Maddy in harm’s way. Later, in the van, Goldie excitedly yells, “Maddy almost got raped, and we just stole this car!” as if this is a source of exhilaration or a mark of resiliency. Perhaps we’d correct her by shifting the blame from the “almost-victim” to her attacker: “Dana and his boys almost raped Maddy.”

Obviously, these are young women just blossoming in their feminist ideals, on the path to realization, and just beginning to question the patriarchal agenda they find themselves a part of in this awkward stage of young adulthood. It’s in this queer in-between state, straddling womanhood and adolescence, that we find Maddy, Legs, Violet, Goldie, and Rita, on the cusp of articulating their justified outrage. We may also question, how does one almost get raped? While the girls of Foxfire are young and somewhat inexperienced, with Legs’ help, they quickly obtain this sort of unpleasant, universal knowledge that males can perpetrate sexual violence in order to “put women in their place.” Dana announces, “You girls are getting a little big for yourselves.” We can’t have that. Women who grow, gain confidence, and challenge sexist and oppressive norms can make waves and upset lots of people. While the girls are initially hesitant in trying to find their way and make sense of their lives, Legs is the powerful catalyst for this transition from the young and feminine to the wise and feminist. While the high school jocks attempt to reclaim the power they feel has been threatened or stolen by this group of girls, Legs continues to challenge gender expectations by utilizing violence as well.

Not only does this film pass the Bechdel Test with flying colors, it almost feels as if it’s a joke when the girls do manage to discuss men–like the topic is not something they take seriously or that boys rest only on the periphery of their lives. While Maddy suffers silently in terms of her artistic prowess and boyfriend drama, Rita–seemingly the prudest and most sheltered of the gang–talks casually about masturbation and penis size. However, it’s important to note that when men do make their way into the conversation, it’s at rare, lighthearted moments when the girls are not guarded or suspicious of the tyrannical and predatory men who seem to surround them. The penis-size discussion between Rita and Violet, we must admit, is also quite self-serving and objectifying. Rather than obsess over their appearances or the approval of boys, the girls’ most ecstatic moment is when Violet receives an anonymous note from a younger girl at school, another student Buttinger was harassing who is thankful for what the gang did. The fact that Violet is so pleased that she could help a friendly stranger who was also a target of the same perverted teacher says a lot about the gang’s goals and identity.

Maddy and Legs recognize something in one another, and although theirs is not a sexual relationship, it is no doubt intimate and meaningful. With an amazing soundtrack that includes Wild Strawberries, L7 (wanna fling tampons, anyone?), and Luscious Jackson, and boasting a cast that includes Angelina Jolie and Hedy Burress, Foxfire is undeniably feminist in its message and narrative. With the help of Legs, the girls find agency, and with it, each other. Although most of the girls have been failed by men in some way, Legs offers hope in female friendship and lets her sisters know that male-perpetrated violence can be combated with a switchblade and a swift kick to the balls. Legs arrives like a whirlwind in Maddy’s life and leaves her changed forever. The lovely ladies of Foxfire will make you want to form a girl gang, dangle off bridges, and break into your old high school’s art room just to stick it to the man.

_____________________________

Jenny holds a Master of Arts degree in English, and she is a part-time instructor at a community college in Pennsylvania. Her areas of scholarship include women’s literature, menstrual literacy, and rape-revenge cinema. She lives with two naughty chihuahuas. You can find her on WordPress and Pinterest.