This post by Ren Jender is part of our theme week on Reality TV and includes part 2 of an interview with documentary filmmaker Barbara Kopple.

Those of us who generally avoid reality TV programming would be wise to remember the genre attracts audiences for legitimate reasons. So many movies and television are based on lies: even those supposedly “based-on-fact” are riddled with enough revision and omission to make their stories unrecognizable–Slate has taken to posting a semi-regular column on how far the latest bio-pic diverges from reality. Audiences hungering for more genuine programming shouldn’t be a surprise.

When audiences tune into reality TV they are also often looking for images they don’t see onscreen otherwise–women who use wheelchairs going about their business without “uplifting” music crescendoing in the background, Black families hanging out together at home without a laugh track, women who aren’t a size 2 with sex lives that aren’t a punch line.

The problem with most reality TV is that much of it isn’t very satisfying, like eating a bag of potato chips when what one really craves is a full meal. In spite of its name, reality TV still has a lot of fakery in it: scenes edited together to create the illusion of tension where none exists, scripts that the “stars” know to follow whether they are part of “reality” or not and women with glamorous hair and makeup when their real-life counterparts bear little resemblance to women on magazine covers.

A channel that has been delivering a less tempered version of “reality” TV for many decades is PBS, most consistently and interestingly for over 25 years on POV, which showcases independent documentaries with limited theatrical runs (and many of those films are available online to watch as well). In its history POV has put its spotlight on trans* and queer people, people of color, and people with disabilities often in work directed by people who are from those communities (which is not usually the case in other “reality” programming). For many years POV was one of the only places on TV to see nuanced portraits of these people, especially before cable TV (and platforms like Netflix and Amazon) started to produce their own content.

POV and documentaries in general have, historically, a far more proportionate share of women directors than the rest of the film and television industry. Barbara Kopple has been directing documentaries since the 1970s, has won two Oscars and her work has been featured, among many other places, on PBS. In part 2 of an interview I conducted with her (part 1 is here) she talks about how she began her career and the challenges through the years of making films about real people living their lives.

(This interview was edited for concision and clarity.)

Bitch Flicks: I’m wondering about your own beginnings as a filmmaker. You worked in a collective at first and with the Maysles brothers. That was the early ’70s and there were hardly any women in filmmaking then. Did you always see yourself going into directing?

Barbara Kopple: I think I did. Because I started learning everything I could possibly learn. This woman who became one of my best friends, Barbara Jarvis, who is now passed away– I’m her daughter’s godmother– I started at Maysles and she would leave me work to do at night, so I’d do the assistant editor’s work, which is what she was, at night, so I would learn. And then I got a job with this guy who was an editor and he would say to me, “OK, I’m going out to lunch and I want you to edit this piece down from 20 minutes to five minutes by the time I get back.” I started to learn storytelling. And also doing Winter Soldier, being part of that wonderful collective. I just loved talking to people. I had this incredible curiosity. Then Harlan County came up and I was able to get a loan of $12,000 to start doing it.

BF: So that was a personal loan that you got? It wasn’t from a foundation or anything?

Kopple: It was just from a producer named Tom Brandon, now passed away. I was searching everywhere to try to find money and he gave me $12,000 and I paid him back.

BF: How long did it take you?

Kopple:: Until the film was finished, and then I got a very small advance and I paid all my debts with him.

BF: That’s amazing. I know that you lived among and followed the people in Harlan County, USA for a long time to get the film that you made.

Kopple: In Harlan County we were machine-gunned. A miner was killed by a foreman, the picket lines… I mean, every day something was happening. You couldn’t miss a moment.

BF: I realize you’ve directed a wide range of things. Have you always felt free in filming people?

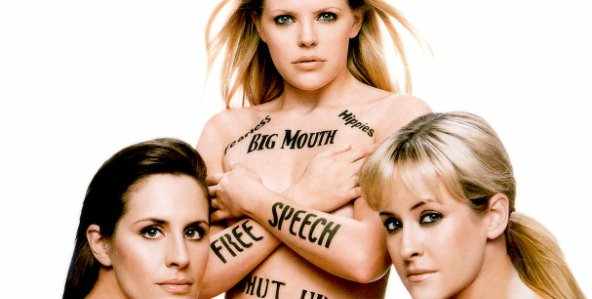

Kopple: Yeah. The Dixie Chicks let us sit in on all their intimate moments…And Gregory Peck and all of them.

BF: So nobody has said, “I feel like this scene shows me in a really unflattering light, like in a big way.”

Kopple: Someone would close the door in our face in American Dream before we would go in. I would just open it, and sometimes, you know, when things were really tough and people were upset, they’d make me say why I wanted to film them, and then I’d get up in front of the room and say why and then they would vote and they would say, “OK.” I’d only been there months and months and months.

BF: Was that in a union setting?

Kopple: Yeah.

BF: But that’s still really amazing because quite a few people, even those who are interested in filming others would be like, “Wait a minute.”

Kopple: Then they wouldn’t do it! All these people wanted to do it. These people said, “Yes.” And if you want to do it, maybe you don’t understand what that means at the beginning…

BF: But eventually you do.

Kopple: Absolutely

BF: Now more and more women are making films, but the problem is: many have short careers, even if their films win awards, even if they really want to direct and they’re really trying to continue their careers as directors. And I’m wondering if you can think of specific things–because you’ve had a really long career–that have helped you to go from project to project. Because, correct me if I’m wrong, it seems like you haven’t taken much of a break.

Kopple: No. I probably should! I don’t know. I guess that I just…somebody will call me and say, “How would you like to do a film on…” and I’m a girl who can’t say no. I do it. I mean, I’m finishing a film now on The Nation magazine; they’re about to have their 150th anniversary in 2015, and we’re finished shooting a film on Sharon Jones and The Dap-Kings. And we’re doing a very short piece on homeless veterans. I love working. I love the curiosity of it, I love learning about people and being out there. [It’s made] my life so rich and so full. Of course I don’t do it for the money, because I can hardly keep my head above water most of the time. I do it because I love it. It doesn’t seem like so many years. Each film is just very magical and exciting and different, and it gives you energy rather than taking it away, so I really just consider it an honor to be doing what I’m doing.

BF: If you could give advice to women who are making films now, what do you think it would be?

Kopple: I think it would be that you’re not alone that there’s tons of people out there who will help you. And only care about the story. Don’t… some people get hung up in, like, the technical, and that’s not what the story is about. It’s about the people. If you feel passionate about something, that passion’s going to flow to a lot of other people and you’re going to be able to do it. [It’s not] easy. You have your ups and your downs. I have my ups and my downs all the time.

BF: Even now?

Barbara Kopple: Yeah! I mean some things get really small budgets and I really want to make these films, so I don’t care about the money, and then I don’t know where to get it to keep paying electricity, to keep the place (her production company) going, but I just figure the films in the end are what’s going to matter. You want to put it out there. I used to dream that some white knight on a horse would come and say, “Here, do whatever you want.” Cinderella wants her lover and I want somebody to care about these films.

___________________________________________________

Ren Jender is a queer writer-performer/producer putting a film together. Her writing. besides appearing every week on Bitch Flicks, has also been published in The Toast, RH Reality Check, xoJane and the Feminist Wire. You can follow her on Twitter @renjender