|

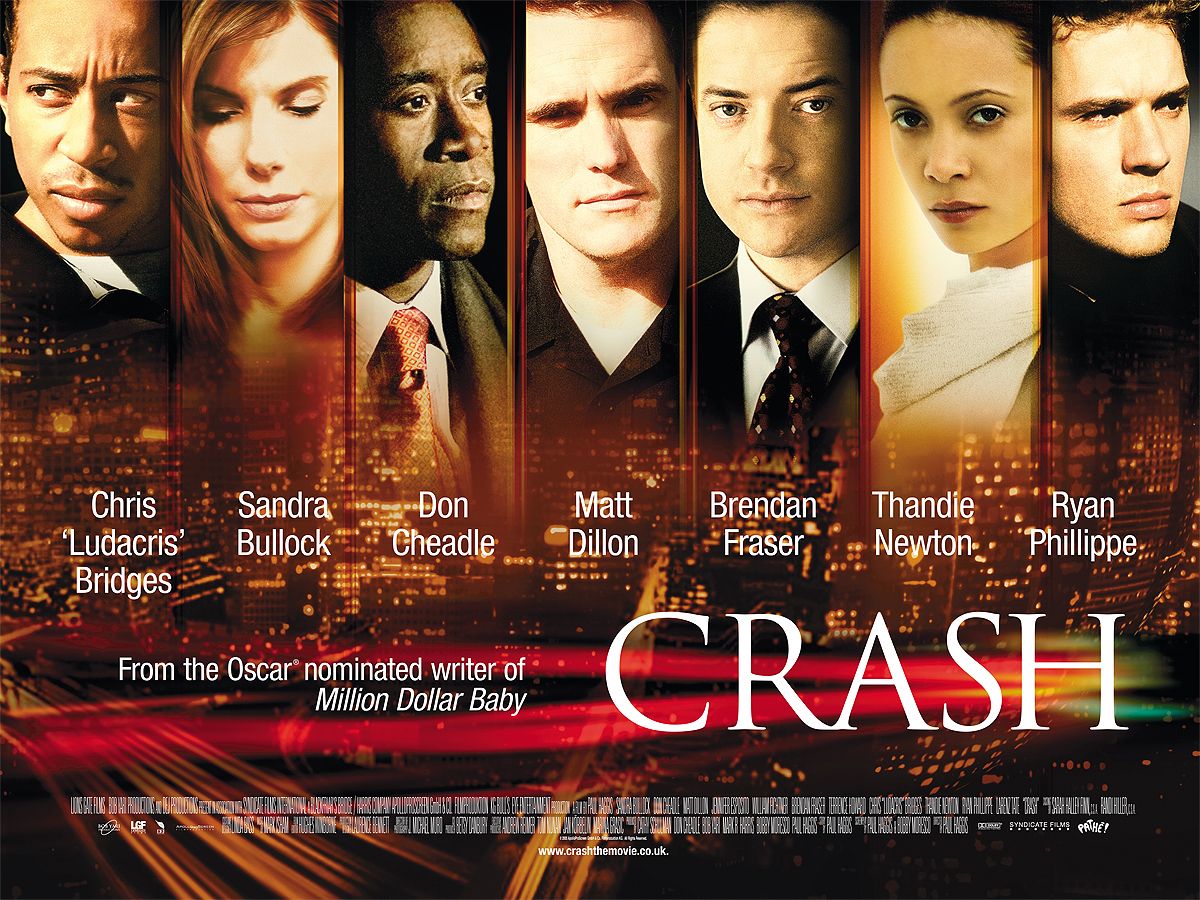

| Crash (2004) |

Tag: Uncategorized

Women of Color In Film and TV: Conflicting Thoughts On ‘Sita Sings The Blues’

|

| In the film’s opening sequence, Sita rubs Rama’s leg. |

|

| “Big, round, firm, juicy…LOTUSES!” |

- I love that this is a successful indie film written, directed, edited and produced by a single woman, Nina Paley, and the film is about a woman of colour. You can really tell this was a labour of love for her, and it’s an incredible achievement that one animator was able to do a feature length film on her own. The film is also explicitly meant to be feminist – in a long summary of the film that she released to the press, she described Sita Sings the Blues as “a tale of truth, justice, and a woman’s cry for equal treatment.” I hope to see more films helmed by women, and not just independent ones. I know that women of colour have an even harder time getting recognized as filmmakers, and I would like to see this same story retold from someone who grew up in Hindu culture, as opposed to a westerner. WOC filmmakers often do not get given a chance to succeed, as they are never given funding nor marketing, and naturally blamed for their films’ financial failure. Quite a vicious cycle. I would love to see more ways for feminist film lovers to discover films made by women and women of colour.

- One of my favourite things in the world is animation, so this film’s widely varying animation styles (and narrative styles that change with the visuals) was such eye candy for me. If I’m counting correctly, there are 6 styles of animation used in this film. The film starts with a stylized Sita rubbing Rama’s leg (depicted in the animated gif at the top), led by stylized and symbolic depictions of the gods. It then rotates into other animation styles. Nina Paley’s autobiographical portions are done in a scribbly, loose style. The 3 Indians who narrate the story are represented as shadow puppets. The Ramayana characters’ dialogue is shown through two different forms of Indian-style artwork – one with lots of detail and bright colours, one with wide, expressive eyes and simple use of colour. The bulk of the film is devoted to Annette Hanshaw jazz songs as “performed” by Sita to complement the narrative. The sequences are presented in a modern vector graphic style, with lots of circles used in the character designs, and is even more stylized in presentation than the introductory sequence. Finally, one scene depicts an Indian woman drawn in white stencil dancing in flames and singing to Rama (it’s kind of hard to describe). Because the visual and narrative styles rotate so quickly (no portion is over 5 minutes) the story keeps you interested and you never stay in one style long enough to get bored.

- I love the Annette Hanshaw sequences, but I have to say, my favourite parts of the film are when three English-speaking Indians from various parts of the country, Aseem Chhabra, Bhavana Nagulapally, and Manish Acharya, narrate the story of The Ramayana and are represented as shadow puppets. I love listening to the very subtle differences in their accents, and how the oral tradition of the story has subtle variations depending on cultural location. I’m just sorry they weren’t identified by name (I had to use the Wiki to credit them) so I could tell them apart beyond “Two males, one female.” Because their discussions are unscripted and they are reciting the story from memory, they make lighthearted jokes about the story, modernize some of the language (one describes Sita telling her kidnapper Ravana that his “ass is grass.”), argue mildly about details and names, and point out some of the plot holes. I laughed out loud when the three agreed that Sita left a trail of jewelry for Rama to follow, then one wondered how much jewelry Sita was wearing to be able to drop jewels for that long a distance. In response, another one says, “Don’t challenge these stories!” I also found it interesting that as they told the story, they questioned some of its details. Ravana is supposedly unquestionably the villain, yet had a past of being learned and a noble warrior. They wondered why he would be so out of character as to kidnap another man’s wife. One also marvelled that the supposed villain did not do the cliche thing and force himself upon Sita. I think questioning and analysis of one’s own culture is a good thing, so I really ate up the shadow puppets’ discourse on The Ramayana.

- Probably the most popular sequences of the film are the stylized vector graphics of an impossibly curvy (she’s all boobs and hips and almost no waist) Sita “singing” jazz and blues songs performed by 1920s singer Annette Hanshaw. Hanshaw has this incredible ability to filter deep emotion through her voice, and having Sita perform these songs gives her a necessary amount of emotional depth. All we know of Sita via the narration is that she is absolutely devoted to her husband, no matter what. The Hanshaw songs thus have Sita expressing joy, adoration, heartbreak, hope, and acceptance, while still maintaining that necessary devotion to Rama. This is important since, no matter how you approach the story, Sita has a very tough time and is treated unfairly – we know that Ravana never touched her and Sita has only ever been with Rama, but she is still punished for even the possibility that another man touched her. The woman whose agency was taken from her should be given a way to express herself, so the blues sequences are a nice compromise.

- Finally, the gif above depicts another one of the better points of the film, which is its sense of humour. In this scene, Ravana’s sister is trying to tempt him to kidnap Sita by describing her beauty. She says, “Her skin is fair like the lotus blossom. Her eyes are like lotus pools. Her hands are like, um, lotuses. Her breasts are like big, round, firm, juicy…LOTUSES!” Sita’s story is unquestionably a tragedy, so the little sprinklings of humour here and there keep the movie from being emotionally draining. I like the use of deliberate anachronisms to emphasize the differences between the ancient Indian setting, and the modern culture of today. Annette Hanshaw’s songs reference technologies that naturally wouldn’t have existed in ancient times, so Paley instead has Sita humorously hold a banana next to her ear when Annette sings about using a phone. And as I mentioned before, the little jokes that the shadow puppet narrators make (and their disagreements on plot details and names) help to make the narrative as lighthearted as possible. I admit I really dislike films that depress me, so this narrative decision appealed to me.

|

| Sita sings “Mean To Me” while going through her trial by fire |

- Okay, now for the flaws. The autobiographical bits retelling the end of Nina Paley’s marriage are terrible. They drag the story to a screeching halt, the loose, drab and scribbly animation style contrasts far too much with the sumptuous and colourful styles used in the other animation sequences, and the story seems far too biased towards Nina’s perspective. I naturally don’t know the details of what really happened, but I have trouble believing that Nina’s former husband Dave is as selfish, heartless, sexless and aloof as she depicts him as being. There had to have been a reason he suddenly lost interest in her beyond their being separated by his job for some months. And I feel so uncomfortable discussing a woman’s personal life, and yet she put this stuff right in her movie, so I can’t help but talk about it! I really think that the autobiographical portions should not have been in the film. It might have been cathartic for her, but it’s awkward for everyone else.

- Another big problem with the autobiographical portions is that I think it’s going too far for Ms. Paley to directly identify herself and the end of her marriage with Sita and her marital problems. Sita and Rama are more-or-less Hindu gods, so for a mortal white woman to compare herself with them has to come off as kind of blasphemous and egotistical. I’m glad she found comfort and inspiration in reading The Ramayana, but I would have left that revelation as perhaps a footnote or just a single scene. The autobiographical bits are interspersed throughout the film to contrast/compare directly to the chapters of Sita’s story, so you’re quite obviously supposed to identify the two women together. There are lots of western films where a character is meant to be a Jesus analogue or is Messianic in some way, but it is almost always a symbolic comparison, not an overt one. There’s no attempt at symbolism here, and I have to wonder if it would still be acceptable even if it was purely symbolic.

- Ms. Paley is also unfortunately channelling her grief and anger over the end of her marriage through her depiction of Rama. This is supposed to be the most virtuous and wise man living, and yet the film depicts him as cruel, cold, weak-willed and stubborn. I, too, would question his supposed perfection after he continued to doubt Sita after she already passed his trial by fire (depicted in the gif above). But I think his character has to have been exaggerated somewhat in this film. Some of the people writing objections have argued that in The Ramayana, Rama was extremely broken-hearted and reluctant to banish Sita, but she loved him so much she persuaded him to send her away so that he could be an effective ruler for his people. That’s some extraordinarily self-sacrificing behaviour on Sita’s part, but it seems much more plausible considering the first half of the story is emphasizing how much they absolutely love each other.

- This negative depiction of Rama goes as far as to basically make him the real villain of the story instead of Ravana. He is even shown kicking, pushing and walking over Sita while she is heavily pregnant. WHOA. It’s really going way too far to depict a man of being a domestic abuser if there isn’t any evidence for it. Again, this is an avatar of a god, and even though he has made a mistake in doubting Sita and sending her away (putting his own reputation amongst his people above the love of his wife), this exaggeration of his character is offensive. When Sita bears Rama’s twin sons and they are raised to praise him, they even sing a sarcastic song about how great and wonderful Rama is and that his word should never be questioned. I get the feminist attempt to question why the man’s judgement is always accepted above the rights of the woman, but the questioning should be directed at their own culture, not someone else’s. Just like we don’t like it when other cultures judge us by their standards, we don’t have the right to judge them by ours either.

- The film’s biggest problem is that it is judging ancient Hindu mythology and custom by modern western feminist standards. If a modern western story came out where a wife is kidnapped, her kidnapper demands to marry her but does not rape her, she is rescued, her husband fears that she has been “tainted,” she proves she hasn’t, and yet is still suspected by others, and is ultimately banished while pregnant with her husband’s sons, and the husband is still depicted as the hero of the story, I would understand the virulent criticism. But because this is the story of the Ramayana, it’s not fair for a white feminist to start complaining about it, and then create a film which reflects mostly her views without making it clear she’s taking liberties with the story. Yes, it’s obvious that Sita never sang jazz songs, but it’s not so obvious that Rama wasn’t actually as cold and cruel to her as he is depicted in this film.

- This unfortunately reeks of the cliche where white feminists go to women of colour and start telling them that they are oppressed by their culture and condescendingly try to “free” them from it. Women of colour can speak for themselves and make up their own minds. That’s what intersectionality is all about – we do not tell people of other cultures (and gender identities, and sexualities, etc etc) how they’re supposed to act and think. The first time I saw this film a few years ago, I was just as angry at Rama as Ms. Paley wants me to be, because I was completely ignorant of the story. It wasn’t until I started researching for this review that I found out that, wait a sec, she’s not depicting him accurately or fairly. When you have the influence to present another religion’s story to an audience that is likely going to be unfamiliar with it, the responsible thing to do is to either depict it accurately, or make it clear that it is an exaggeration. Sita Sings the Blues’ messages have unfortunately been diluted because of this strongly problematic element.

Myrna Waldron is a feminist writer/blogger with a particular emphasis on all things nerdy. She lives in Toronto and has studied English and Film at York University. Myrna has a particular interest in the animation medium, having written extensively on American, Canadian and Japanese animation. She also has a passion for Sci-Fi & Fantasy literature, pop culture literature such as cartoons/comics, and the gaming subculture. She maintains a personal collection of blog posts, rants, essays and musings at The Soapboxing Geek, and tweets with reckless pottymouthed abandon at @SoapboxingGeek.

A Post About ‘Community’s Shirley? That’s Nice.

Written by Lady T.

|

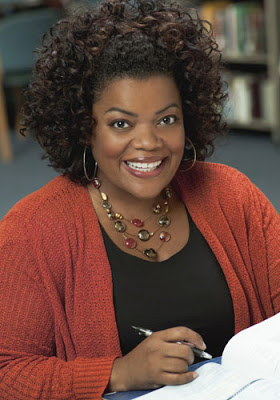

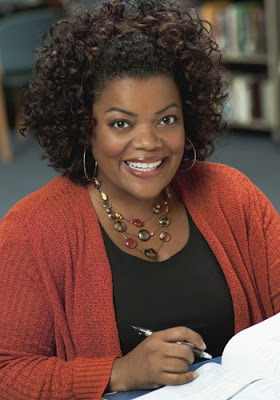

| Yvette Nicole Brown as Shirley Bennett on Community |

Anyone who has absorbed even a little bit of pop culture can see that the “sassy ethnic woman” archetype is ubiquitous in television and film. Women of color – particularly black and Latina women – are often used as sassy, finger-snapping side characters who exist only to provide amusing one-liners in the background of whatever white person drama or comic event happening in the forefront. (On a great scene from Scrubs, Carla and Laverne demonstrate how to act like a “minority sidekick from a bad movie”:)

One refreshing departure from the “sassy ethnic woman” stereotype is Shirley Bennett on Community. Played by Yvette Nicole Brown, Shirley is one of four people of color in the show’s main cast, though the only woman of color. In an interview with The Daily Beast, which included cast members Alison Brie and Gillian Jacobs and writer Megan Ganz, Brown discussed why Shirley is a refreshing character for her to play:

As a black actor, it’s refreshing that I’m not playing the “sassy black woman.” It’s something that Dan Harmon was cognizant of from the beginning. It is something that I’m always cognizant of. Every woman on the planet has sass and smart-ass qualities in them, but it seems sometimes only black women are defined by it. Shirley is a fully formed woman that had a sassy moment. Her natural set point, if anything, is rage. That’s her natural set point, suppressed rage, which comes out as kindness and trying to keep everything tight.

Shirley is, perhaps, the only main character on Community who has her own catchphrase, but the catchphrase – “That’s nice!” – is a far cry from the finger-snapping talking-through-the-nose stereotype demonstrated on the above clip from Scrubs. Shirley is exactly what Brown described: a woman filled with suppressed rage who covers up her anger by trying to be sweet and kind. But rather than being an example of a different kind of negative black stereotype – the Angry Black Person who bursts into a rage for no stated reason – the Community writers and Brown show that Shirley has plenty of reasons to be angry.

Like the other members of the Spanish study group, Shirley comes to Greendale Community College when she needs to start a new chapter in her life after the first chapter ended badly: her husband abandoned her and their two children, and she wants to earn a business degree so she can sell her baked goods. Christian and motherly, Shirley takes on a protective nature to the youngest members of the group (Annie, Troy, and Abed), tries to develop a camaraderie with Britta and act as a cheerleader for her flirty dynamic with Jeff, and does her best to ignore the sexual harassment from Pierce.

|

| Annie (Alison Brie), Britta (Gillian Jacobs), and Shirley get caught in a “reverse Porky’s” shenanigan |

Soon, Shirley develops close bonds with other members of the study group, trying to keep the group dynamic sweet, light, and happy – but time and time, her repressed anger rises to the surface.

Shirley flies into a rage when Jeff shows interest in a woman other than Britta, acting indignant on Britta’s behalf, but she later admits that she’s still in deep pain over her own divorce: “I was too proud to admit I was hurt, so I had to pretend you were,” she says to her friend.

Shirley is put out and offended when her friends don’t want to attend her Christmas party, taking their reluctance as an insult to her faith, but again, Britta gets to the heart of the matter: Shirley is desperate to recreate a tradition that’s important to her, that’s missing from her life since her painful divorce.

Shirley, when given a chance to act as campus security with Annie for a few days, insists on being the “bad cop” of the duo, a role that Annie also claims. The two characters clash during most of the episode because both are desperate for a change in image. While Annie wants people to stop seeing her as a sweet little girl, Shirley wants people to stop seeing her as a sweet motherly type. (More on that in a minute.)

|

| Annie and Shirley as campus security officers |

In short: Shirley has a lot of anger. What makes Shirley’s anger so refreshing is that her anger is not portrayed as a sign of her blackness, or her womanhood, but as the sign of a flawed, complex human being with legitimate pain. Sometimes her anger is towards a perceived slight that has nothing to do with her (assuming that her friends judge her for her Christianity when they don’t), and sometimes her anger is completely justified (getting fed up with Pierce’s harassment and racist comments). Sometimes she’s wrong, and sometimes she’s right – just like any other person.

Anger isn’t a character trait limited to Shirley, either. Annie also has repressed rage. The two women have a lot in common, “aww”-ing over cute things and getting upset when they’re not taken seriously. But of all the other characters in Community, Shirley seems to have the closest bond with Jeff. On the surface, they have little in common – he’s a white playboy sarcastic former lawyer, she’s a married black Christian woman with children – but just as Shirley covers her anger with a layer of sweetness, Jeff covers his with layers of blasé indifference. The fact that a young, insecure Shirley turns out to be Jeff’s former bully from when they were children seems perfect for their characters, and their friendship deepens – and some of their anger is assuaged – after they confront this issue.

|

| Jeff (Joel McHale) and Shirley, BFFs (sort of) |

Sometimes the writers on Community give Shirley short shrift compared to the other characters, as if they’re not sure what to do with a woman who is now re-married and in a happy relationship (their strengths are in writing damaged people, not content people). I’d also like the show to further explore her complicated dynamic with Britta, a woman with whom Shirley craves close friendship, but also finds threatening. Still, I’m grateful that Community allows Shirley to be as flawed, funny, and complicated as everyone else at Greendale Community College. She’s my younger brother’s favorite character, and I think that’s nice.

———-

As a black actor, it’s refreshing that I’m not playing the “sassy black woman.” It’s something that Dan Harmon was cognizant of from the beginning. It is something that I’m always cognizant of. Every woman on the planet has sass and smart-ass qualities in them, but it seems sometimes only black women are defined by it. Shirley is a fully formed woman that had a sassy moment. Her natural set point, if anything, is rage. That’s her natural set point, suppressed rage, which comes out as kindness and trying to keep everything tight. – See more at: http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2012/02/28/community-alison-brie-yvette-nicole-brown-gillian-jacobs-megan-ganz-roundtable.html#sthash.cAOgrEkS.dpufAs a black actor, it’s refreshing that I’m not playing the “sassy black woman.” It’s something that Dan Harmon was cognizant of from the beginning. It is something that I’m always cognizant of. Every woman on the planet has sass and smart-ass qualities in them, but it seems sometimes only black women are defined by it. Shirley is a fully formed woman that had a sassy moment. Her natural set point, if anything, is rage. That’s her natural set point, suppressed rage, which comes out as kindness and trying to keep everything tight. – See more at: http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2012/02/28/community-alison-brie-yvette-nicole-brown-gillian-jacobs-megan-ganz-roundtable.html#sthash.cAOgrEkS.dpufAs a black actor, it’s refreshing that I’m not playing the “sassy black woman.” It’s something that Dan Harmon was cognizant of from the beginning. It is something that I’m always cognizant of. Every woman on the planet has sass and smart-ass qualities in them, but it seems sometimes only black women are defined by it. Shirley is a fully formed woman that had a sassy moment. Her natural set point, if anything, is rage. That’s her natural set point, suppressed rage, which comes out as kindness and trying to keep everything tight. – See more at: http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2012/02/28/community-alison-brie-yvette-nicole-brown-gillian-jacobs-megan-ganz-roundtable.html#sthash.cAOgrEkS.dpuf

Women of Color in Film and TV: A Post About ‘Community’s; Shirley? That’s Nice.

Written by Lady T.

|

| Yvette Nicole Brown as Shirley Bennett on Community |

Anyone who has absorbed even a little bit of pop culture can see that the “sassy ethnic woman” archetype is ubiquitous in television and film. Women of color – particularly black and Latina women – are often used as sassy, finger-snapping side characters who exist only to provide amusing one-liners in the background of whatever white person drama or comic event happening in the forefront. (On a great scene from Scrubs, Carla and Laverne demonstrate how to act like a “minority sidekick from a bad movie”:)

One refreshing departure from the “sassy ethnic woman” stereotype is Shirley Bennett on Community. Played by Yvette Nicole Brown, Shirley is one of four people of color in the show’s main cast, though the only woman of color. In an interview with The Daily Beast, which included cast members Alison Brie and Gillian Jacobs and writer Megan Ganz, Brown discussed why Shirley is a refreshing character for her to play:

As a black actor, it’s refreshing that I’m not playing the “sassy black woman.” It’s something that Dan Harmon was cognizant of from the beginning. It is something that I’m always cognizant of. Every woman on the planet has sass and smart-ass qualities in them, but it seems sometimes only black women are defined by it. Shirley is a fully formed woman that had a sassy moment. Her natural set point, if anything, is rage. That’s her natural set point, suppressed rage, which comes out as kindness and trying to keep everything tight.

Shirley is, perhaps, the only main character on Community who has her own catchphrase, but the catchphrase – “That’s nice!” – is a far cry from the finger-snapping talking-through-the-nose stereotype demonstrated on the above clip from Scrubs. Shirley is exactly what Brown described: a woman filled with suppressed rage who covers up her anger by trying to be sweet and kind. But rather than being an example of a different kind of negative black stereotype – the Angry Black Person who bursts into a rage for no stated reason – the Community writers and Brown show that Shirley has plenty of reasons to be angry.

Like the other members of the Spanish study group, Shirley comes to Greendale Community College when she needs to start a new chapter in her life after the first chapter ended badly: her husband abandoned her and their two children, and she wants to earn a business degree so she can sell her baked goods. Christian and motherly, Shirley takes on a protective nature to the youngest members of the group (Annie, Troy, and Abed), tries to develop a camaraderie with Britta and act as a cheerleader for her flirty dynamic with Jeff, and does her best to ignore the sexual harassment from Pierce.

|

| Annie (Alison Brie), Britta (Gillian Jacobs), and Shirley get caught in a “reverse Porky’s” shenanigan |

Soon, Shirley develops close bonds with other members of the study group, trying to keep the group dynamic sweet, light, and happy – but time and time, her repressed anger rises to the surface.

Shirley flies into a rage when Jeff shows interest in a woman other than Britta, acting indignant on Britta’s behalf, but she later admits that she’s still in deep pain over her own divorce: “I was too proud to admit I was hurt, so I had to pretend you were,” she says to her friend.

Shirley is put out and offended when her friends don’t want to attend her Christmas party, taking their reluctance as an insult to her faith, but again, Britta gets to the heart of the matter: Shirley is desperate to recreate a tradition that’s important to her, that’s missing from her life since her painful divorce.

Shirley, when given a chance to act as campus security with Annie for a few days, insists on being the “bad cop” of the duo, a role that Annie also claims. The two characters clash during most of the episode because both are desperate for a change in image. While Annie wants people to stop seeing her as a sweet little girl, Shirley wants people to stop seeing her as a sweet motherly type. (More on that in a minute.)

|

| Annie and Shirley as campus security officers |

In short: Shirley has a lot of anger. What makes Shirley’s anger so refreshing is that her anger is not portrayed as a sign of her blackness, or her womanhood, but as the sign of a flawed, complex human being with legitimate pain. Sometimes her anger is towards a perceived slight that has nothing to do with her (assuming that her friends judge her for her Christianity when they don’t), and sometimes her anger is completely justified (getting fed up with Pierce’s harassment and racist comments). Sometimes she’s wrong, and sometimes she’s right – just like any other person.

Anger isn’t a character trait limited to Shirley, either. Annie also has repressed rage. The two women have a lot in common, “aww”-ing over cute things and getting upset when they’re not taken seriously. But of all the other characters in Community, Shirley seems to have the closest bond with Jeff. On the surface, they have little in common – he’s a white playboy sarcastic former lawyer, she’s a married black Christian woman with children – but just as Shirley covers her anger with a layer of sweetness, Jeff covers his with layers of blasé indifference. The fact that a young, insecure Shirley turns out to be Jeff’s former bully from when they were children seems perfect for their characters, and their friendship deepens – and some of their anger is assuaged – after they confront this issue.

|

| Jeff (Joel McHale) and Shirley, BFFs (sort of) |

Sometimes the writers on Community give Shirley short shrift compared to the other characters, as if they’re not sure what to do with a woman who is now re-married and in a happy relationship (their strengths are in writing damaged people, not content people). I’d also like the show to further explore her complicated dynamic with Britta, a woman with whom Shirley craves close friendship, but also finds threatening. Still, I’m grateful that Community allows Shirley to be as flawed, funny, and complicated as everyone else at Greendale Community College. She’s my younger brother’s favorite character, and I think that’s nice.

———-

As a black actor, it’s refreshing that I’m not playing the “sassy black woman.” It’s something that Dan Harmon was cognizant of from the beginning. It is something that I’m always cognizant of. Every woman on the planet has sass and smart-ass qualities in them, but it seems sometimes only black women are defined by it. Shirley is a fully formed woman that had a sassy moment. Her natural set point, if anything, is rage. That’s her natural set point, suppressed rage, which comes out as kindness and trying to keep everything tight. – See more at: http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2012/02/28/community-alison-brie-yvette-nicole-brown-gillian-jacobs-megan-ganz-roundtable.html#sthash.cAOgrEkS.dpufAs a black actor, it’s refreshing that I’m not playing the “sassy black woman.” It’s something that Dan Harmon was cognizant of from the beginning. It is something that I’m always cognizant of. Every woman on the planet has sass and smart-ass qualities in them, but it seems sometimes only black women are defined by it. Shirley is a fully formed woman that had a sassy moment. Her natural set point, if anything, is rage. That’s her natural set point, suppressed rage, which comes out as kindness and trying to keep everything tight. – See more at: http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2012/02/28/community-alison-brie-yvette-nicole-brown-gillian-jacobs-megan-ganz-roundtable.html#sthash.cAOgrEkS.dpufAs a black actor, it’s refreshing that I’m not playing the “sassy black woman.” It’s something that Dan Harmon was cognizant of from the beginning. It is something that I’m always cognizant of. Every woman on the planet has sass and smart-ass qualities in them, but it seems sometimes only black women are defined by it. Shirley is a fully formed woman that had a sassy moment. Her natural set point, if anything, is rage. That’s her natural set point, suppressed rage, which comes out as kindness and trying to keep everything tight. – See more at: http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2012/02/28/community-alison-brie-yvette-nicole-brown-gillian-jacobs-megan-ganz-roundtable.html#sthash.cAOgrEkS.dpuf

Women of Color in Film and TV: A Celebration of Black Women on Film in 2012

|

| Beasts of the Southern Wild |

|

| Joyful Noise |

|

| Django Unchained |

|

| Middle of Nowhere |

|

| Won’t Back Down |

“Beloved, you are my sister, you are my daughter, you are my face; you are me.” –Toni Morrison

Women of Color in Film and TV: Talk About a ‘Scandal’: ‘Bunheads,’ the Whitey-Whiteness of TV, and Why Shonda Rhimes Is a Goddamn Hero

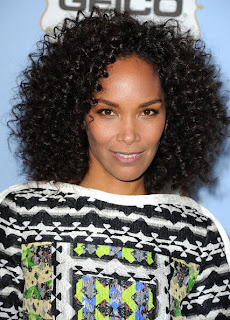

I love Scandal. Halfway through the second season, it’s still some of the most sharp, fast-paced, thrilling TV I’ve ever sat through. Sure, it’s often improbable and features silly banter, but it’s never predictable, and Kerry Washington shines like the star she is as clever, controlled, morally ambiguous “crisis manager” Olivia Pope. (Yes, she’s the Pope.) (Oh, if only.)

What I don’t love is the fact that Kerry Washington is the first black woman to have the lead in a network drama in my lifetime.

|

| Shonda Rhimes’ Scandal |

I’m in my thirties! And since five years before I was born there hasn’t been a black female lead in an American network drama. (That was one called Get Christie Love!, inspired by the blaxploitation films of the ’70s.) And while there have been Asian and Latina leading ladies in that time, let’s not pretend that TV has ever been full of diversity. It’s a white person’s playground.

So it’s maybe not surprising that when Gilmore Girls creator Amy Sherman-Palladino’s new show Bunheads first aired, Shonda Rhimes, who created Scandal as well as Grey’s Anatomy and Private Practice, felt a little fed up.

She tweeted ABC Family:

“Really? You couldn’t cast even ONE young dancer of color so I could feel good about my kid watching this show? NOT ONE?”

Which seems like a fair comment, as Bunheads‘ lack of diversity is a glaring omission.

It’s great to see a show that’s unabashedly female-centric and more concerned with telling stories than trying to be gimmicky (and which portrays performers with far more subtlety than Smash could ever manage). There are enough shows where women are nothing more than set dressing for it not to be an issue that all six leads in Bunheads are ladies.

But it is an issue that all six leads are white.

It would have been nice if Rhimes’ tweet had launched a respectful debate about the underrepresentation of women of color on TV. Instead, it sent Sherman-Palladino on a self-justifying rant in a horrible interview with Media Mayhem, which was notable for the fact that neither she nor the journalist who questioned her actually stuck to the point. That journalist, Allison Hope Weiner, said that what she took from the incident was that it was “inappropriate” for a woman to criticise another female showrunner, when there are so few of them.

Sherman-Palladino agreed, saying she would never “go after” another woman and that women in TV are not as supportive as they should be. She also pointed out that she only had a week and a half to cast four girls who could act and dance on pointe. Then she said that she doesn’t do “issues shows.”

It’s hard to know where to start with this clusterbleep of wrongness, but how about we begin with the idea that women should always support each other, no matter what?

Rebecca Paller of the Paley Center posted a blog post about the fracas, “Bunheads and Women: Why Can’t We Just Get Along?” in which she supports Sherman-Palladino and scolds Rhimes for her criticism, saying:

“You should have been more supportive of another female showrunner especially in this day and age when it’s so difficult to get a new dramatic series on the air.”

|

| Kerry Washington as Olivia Pope in Scandal |

Saying that women have to be nice to each other at all times because there are so few of us in top jobs only promotes the idea that we’re special snowflakes who have to be treated like precious cargo. While there are men whose shows are similarly lacking in diversity, female solidarity doesn’t preclude valid criticism. And the competitiveness among women that Sherman-Palladino alludes to is surely a symptom of the patriarchy and the fact that it’s so hard for women to get ahead rather than a case of “bitches be loco.”

Even worse, for white women like Sherman-Palladino, Hope Weiner, and Paller to ignore the context of Rhimes’ remark is breathtakingly ignorant. As you might have noticed, America has a history of oppressing both women and people of color and of stereotyping them in popular culture (the Academy is still rarely more impressed than when a black women plays a maid). And yet Paller mentions a possible Asian extra as proof that Bunheads is diverse, and says she’s “still not certain” why Rhimes saw fit to criticise Sherman-Palladino.

Shonda Rhimes is one of very few TV writers creating interesting black female characters. And she’s a black woman. That’s probably not coincidental. Sure, white men could be doing the same thing. But they’re not.

|

| Kerry Washington as Olivia Pope in Scandal |

E.K.: I think the lack of diversity on Girls probably has something to do with HBO’s willingness to let her be very specific, and tell her story. Whereas with network shows, there’s always a mandate. It becomes, “How are we gonna include this group of people?” or “We have to have some diversity.”

W.C.: And then every doctor is black.

E.K.: It becomes a token gesture. It doesn’t come from a place of sincere storytelling, or anything organic to the world.

And sure, we’re talking television here, and not real life. But TV shows matter. They’re probably our biggest shared cultural experience, and how they portray (or ignore) members of historically marginalised groups can reflect and reinforce stereotypes in an insidious way. Helena Andrews wrote a great piece for xoJane about Bunheads and the fact that, had her own ballet teacher not been black, she might not have realized that the white-dominated world of dance was something she could take part in, let alone enjoy:

“In a world that was looking less and less like me just as I was beginning to actually take a look at myself (oh, hey, there puberty) seeing an impossibly elegant (and forgive me) strong black woman every week was more than just a drop in the bucket of my confidence. It was a monsoon.”

Shonda Rhimes knows it does.

———-

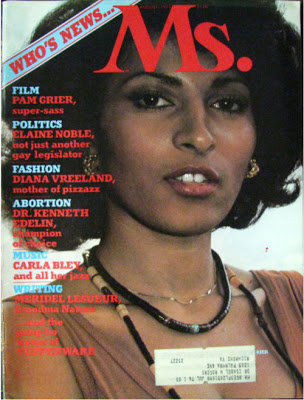

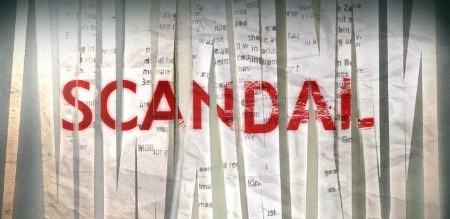

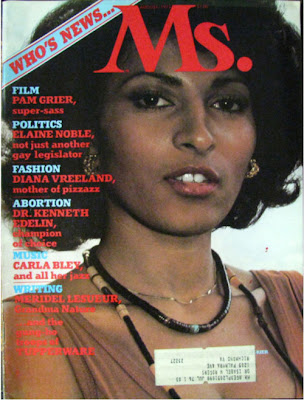

The Unfinished Legacy of Pam Grier

|

| Pam Grier was the first black woman to be on the cover of Ms. Magazine (August 1975). Jamaica Kincaid wrote the article, “Pam Grier: The Mocha Mogul of Hollywood.” |

Written by Leigh Kolb

[Warning: spoilers ahead!]

|

| “This is the end of your rotten life, you motherfuckin’ dope pusher!” |

When she’s going to the neighborhood committee for help at the end, she pleads:

|

| “The party’s over, Oscar, let’s go.” |

|

| “Now you tell your boss that he is not dealing with my father anymore. He is dealing with Sheba Shayne.” |

“I saw women share the platform with men in my personal world, and Hollywood just hadn’t wakened to it yet. Bette Davis and Katharine Hepburn changed the way they saw women during the 1940s, but I saw it daily in the women’s movement that was emerging, because I was a child of the women’s movement. Everything I had learned was from my mother and my grandmother, who both had a very pioneering spirit. They had to, because they had to change flat tires and paint the house—because, you know, the men didn’t come home from the war or whatever else, so women had to do these things. So, out of economic necessity and the freedoms won, by the ’50s and ’60s, there was suddenly this opportunity and this invitation that was like, ‘Come out here with these men. Get out here. Show us what you got.'”

In regard to the nudity, she says,

“We’ve got $20 million actresses today who are nude in Vanilla Sky, nude in Swordfish. So what did I do different? I got paid less, but that’s it.”

“I saw more violence in my neighborhood and in the war and on the newsreels than I did in my movies, so it didn’t bother me. Coming from the ’50s, things were very violent. We were still being lynched. If I drove down through the South with my mother, I might not make it through one state without being bullied or harassed. I feel like unless you’ve been black for a week, you don’t know. A lot of people were really up in arms about nothing, and if you challenge them, they go, ‘Well, maybe you’re right.'”

“You know, Clint Eastwood, Sylvester Stallone, they can all do shoot-’em-ups. Arnold Schwarzenegger can kill 10 people in one minute, and they don’t call it ‘white exploitation.’ They win awards and get into all the magazines. But if black people do it, suddenly it’s different than if a white person does it.”

|

| Jackie Brown |

However, it’s more likely that we get Fighting Fuck Toys (FFTs) in modern cinema, and as Caroline Heldman writes:

“Hollywood rolls out FFTs every few years that generally don’t perform well at the box office (think Elektra, Catwoman, Sucker Punch), leading executives to wrongly conclude that women action leads aren’t bankable. In fact, the problem isn’t their sex; the problem is their portrayal as sex objects. Objects aren’t convincing protagonists. Subjects act while objects are acted upon, so reducing a woman action hero to an object, even sporadically, diminishes her ability to believably carry a storyline. The FFT might have an enviable swagger and do cool stunts, but she’s ultimately a bit of a joke.”

Grier’s heroes are never the joke, and that’s what works. She can carry a storyline, have sex when she wants it (or not) and end up victorious, with her complete agency intact. She’s a subject acting upon the injustices around her.

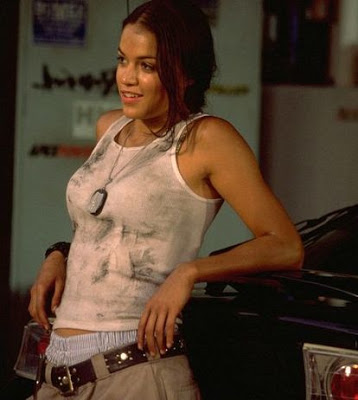

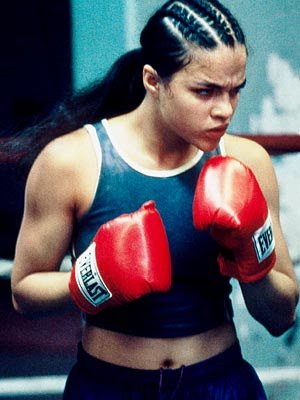

Women of Color in Film and TV: The Conundrum of Butch-Hottie Michelle Rodriguez

Michelle Rodriguez, famous for her roles in “Girlfight”, “The Fast and the Furious” series, and TV series “Lost”, is a cinematic conundrum. Much like most Latina actresses, Rodriguez is typecast. Unlike those Latina actresses who are typecast as extremely feminine and sensual, Rodriguez is typecast as the smoldering, independent bad girl who doesn’t take shit from men. In her roles, Rodriguez embodies many traditionally coded masculine traits (she’s strong, aggressive, mechanically inclined, independent, physical, etc). Despite this perceived masculinity, she is not depicted as a lesbian, and her butch attributes are actually designed to accentuate her sexual appeal.

|

| Michelle Rodriguez as Letty: mechanic, car racer, and thief in The Fast and the Furious series |

|

| Michelle Rodriguez as Diana Guzman in Girlfight |

| Michelle Rodriguez as Ana Lucia Cortez in Lost |

|

| A pre-zombified Michelle Rodriguez as Rain Ocampo in Resident Evil |

|

| Michelle Rodriguez’s sexuality is definitely at the forefront as Shé from Machete |

Women of Color in Film and TV: The Terrible, Awful Sweetness of ‘The Help’

|

| Mmm…empty calories. Like The Help? |

The perfect summer escape for viewers who embrace the fantasy of a postracial America, [where] filmgoers can tuck the history of race and class inequality safely in the past, even as the recession deepens already profound racial gaps in wealth and employment.

Women of Color in Film and TV: ‘Scandal’ Pilot: Loosen Up Your Buttons, Baby

|

| Scandal |

The setup is complete by the end of Scene 5. Everything and everyone we need to know has been established. Now the story is about to get moving. A disabled, Iraq war hero appears in the office lobby with blood on his hands. “My girlfriend. She’s dead,” he says. “And the police think I killed her.” In a comic book, the exclamation point follows the BANG! In this scene, the gun has already gone off and we are seeing the effects of the aftermath. Harrison turns to Quinn and says, “Welcome to Pope and Associates!”

Women of Color in Film and TV: ‘Pariah’

|

| Pariah (2011), a film by Dee Rees |

An astounding, vibrant piece of finely weaved storytelling and thoughtfully spoken artistry, this independent film centers on Brooklyn high school teen, Alike (pronounced ah-lik-e) an exceptionally good student and aspiring poet from a hard-working middle-class family. In her underground world, the shy girl hangs out with bold, outspoken, Laura, who has already proudly come out and lives with her sister.

|

| Bina (Aasha Davis) and Alike (Oduye) in the stages of love |

|

| Alike with Audrey (Kim Wayans) during happier times |

|

| Alike and Arthur (Charles Parnell) after that horrible scene |

|

| Sharonda loves her sister no matter what! |

|

| The lovely, talented Adepero Oduye |

|

| Laura trying to change up Alike’s fashion sense! |

|

| Actress Adepero Oduye, Pariah writer/director Dee Rees, and Actress Kim Wayans |

———-

Janyce Denise Glasper is a writer/artist running two silly blogs of creative adventures called Sugarygingersnap and AfroVeganChick. She enjoys good female-centric film, cute rubber duckies, chocolate covered everything (except bugs!), Days of Our Lives, and slaying nightly demons Buffy style in Dayton, Ohio.

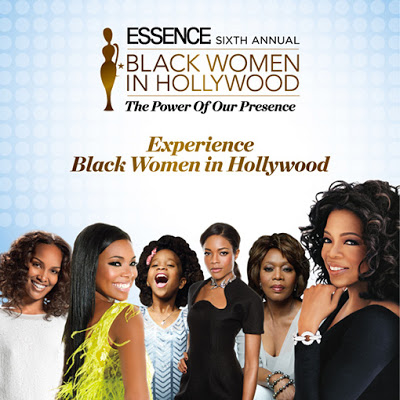

Women of Color in Film and TV: Quotes of the Day: Essence’s Black Women in Hollywood Awards

Last Thursday, Feb. 21, Essence magazine held its sixth annual Black Women in Hollywood awards luncheon.

The honorees were:

Breakthrough Performance – Quvenzhané Wallis

Lincoln Shining Star Award – Naomie Harris

Visionary Award – Mara Brock Akil

Fierce & Fearless Award – Gabrielle Union

Vanguard Award – Alfre Woodard

Power Award – Oprah Winfrey

|

| Nine-year-old Wallis, star of Beasts of the Southern Wild, thanked God, director Behn Zeitlin, and her on-set babysitters. |

|

Union noted that she hadn’t always been “fierce and fearless,” and that she didn’t speak up against racism when she was younger and posed in photographs in ways that would “minimize” her “blackness.” However, she added:

Brock Akil, writer and producer known for Moesha, Girlfriends, Cougar Town, The Game and Sparkle, delivered a tearful speech, saying:

The awards luncheon, held two days before the Academy Awards, celebrates the success of black women writers, producers, actresses and other Hollywood power-brokers. Actress Tracee Ellis Ross says, “It’s a beautiful afternoon where we’re celebrating each other and giving praise to women that don’t always get praised.”

This event by, for and all about black women in Hollywood serves as a celebration of the successes these women have had and as inspiration to the women who will come after them.

|