Written by Jenny Lapekas as part of our theme week on Children’s Television.

Why examine this offbeat show through a feminist or ethical lens? Because Foster’s Home for Imaginary Friends (Craig McCracken, 2004-2009) is wildly inventive and subversive. Its plot, which explains that children’s imaginary friends must eventually go live at Madame Foster’s zany orphanage after he or she has outgrown their friend, insists that a child’s imagination has the power to make something real, whether adults believe it or not. At this home, young children are welcome to come and “adopt” one of the friends who is housed there. In this way, the friends are concepts that are “recycled” in order to accommodate children as they grow up.

There’s a certain level of manic energy present in some of today’s children’s cartoons (see SpongeBob SquarePants), and Foster’s is no exception. It seems as if so much is taking place all at once–most of which is pure nonsense–that we must comb through a cartoon’s goofy dialogue and fast-paced antics to discover central themes of kindness, friendship, and teamwork. I grew up watching David the Gnome, Eureeka’s Castle, Will Quack Quack, Noozles, and Faerie Tale Theatre, all shows that were modest and plodding, patient in their moral messages for kids watching at home. Although Foster’s can be grouped with other kids’ shows that consistently feature a great deal of commotion, this Cartoon Network show boasts some of the most creative characters and engaging plots, even for adults who are fans of clever cartoons with positive messages for everyone. I never had an imaginary friend growing up, and this show is a reminder of that for me.

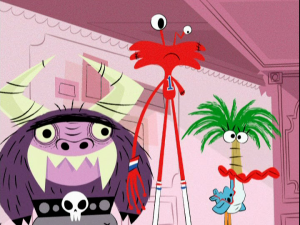

We have an eclectic mix of primary characters who we follow throughout the series. The atmosphere at Foster’s rests somewhere between a low level psych ward and a daycare full of rambunctious trouble-makers. Although female-gendered “friends” are largely underrepresented on the show, the lessons Foster’s has to offer to child viewers are healthy and powerful, as they promote building friendships, using your imagination to have fun, and exploring the world around you.

After a fight with his brother, Terrence, which leaves the apartment in disarray, Mac’s mother tells him that at eight years old, he should have outgrown his imaginary friend, Bloo, by now. The fact that after Mac is forced to surrender his kind imaginary friend, yet continues to visit him every day, is evidence that Mac is not quite ready to grow up yet, and perhaps that’s not such a bad thing. We’re never too old to dream, imagine, and tell stories. This pressure to “grow up” translates to a sort of censorship, which inhibits our creative impulses as adults. We can’t be afraid to embrace nonsense; it can always be the root of something spectacular.

Since the inhabitants of Foster’s are the products of children’s imaginations, it may make more sense to focus on these characters, rather than the humans who help to run the institution. If we simply take a look at the appearance of many imaginary friends, we may surmise that this show is the ultimate lesson in diversity for children viewers. Wilt is very tall with some bodily “deformities,” Eduardo is a Latino creature resembling a bull, and Coco is a bird-like friend whose vocabulary stops at her own name. By observing many of the friends, we get a sense of the psychology behind each creature’s origin. Coco, for example, was dreamed up by a little girl who survives a plane crash and becomes stranded on a desert island; if we look closely, the bird’s head and hair mimic a palm tree, and her body looks like a crashed airplane. In this way, Foster’s can be seen as literally fostering childhood stressors, including the confusion many of us can remember from our early years; the home we find in this cartoon works to make sense of that uncertainty.

Because Coco is the only female character within our primary group of imaginary friends, I think it makes sense to focus on her presence in the home. Foster’s houses dozens of more friends, a few of them female, and many of them become entangled in the lives of the main characters. One secondary female character we meet right away is the insufferable Duchess, who believes that she is the best idea anyone’s ever come up with. This leaves Coco as the only primary character who is an imaginary friend in Foster’s (excluding, of course, the humans who help to run the home). What luck that Coco, in spite of her limited vocabulary (or perhaps because of), is simply delightful.

Because Coco is only able to say her own name, she must alter her tone to let her friends know if she’s happy or upset, or if she’s asking a question or giving a direction, etc. This communication has its own set of rules in relation to the other characters (see Stewie from Family Guy). When Bloo first meets her, he repeatedly says “Yes” because he thinks she’s asking if he’d like some cocoa. However, Wilt understands her and explains that she was offering Bloo some juice.

In the first episode of the series, Coco repeatedly squawks “Coco!” at Eduardo as he rescues Mac from a vicious monster created by a “jerky teenage boy,” and Eduardo eventually says in Spanish, “Yes, thanks, Coco, you have a way with words,” clearly an ironic joke that Coco is adept at resolving tense situations, despite the fact that we can’t understand her on some level. It’s also made clear that when we make friends, we eventually begin to speak the same language, even if outsiders are unable to translate it. The show’s inclusion of a Latino character also exposes children to the Spanish language, which can only be a good thing. This scene also solidifies Eduardo as a character we cannot and should not judge based on appearances alone. Despite his large stature and booming voice (not to mention that he’s a bull!), he’s the gentlest friend at Foster’s and is often terrified of children, another example of comical irony in the cartoon.

In season three, Mac responds to Coco’s “gibberish” with an ominous, “Coco, I think if we did that, we’d go to jail,” alerting us to a darker side of Foster’s and its whimsical friends. Like everything else on the show, her thought is left to our own imaginations. What’s convenient and exciting about having Coco around is that she can lay eggs that contain fun prizes. She’s so excited when Bloo arrives at Foster’s that she lays an egg filled with a Ming vase, in addition to a bundle of other mysterious items that Mac carries off when he leaves. Coco also proves her kindness on Bloo’s first night at Foster’s when she gives him an egg with Mac’s photo inside.

Coco is important not only because she’s one of the only female characters in the house, but because her presence is a mark of understanding: that childhood is its own language, and that play and learning are interconnected and necessary for growth. What children can take away from Foster’s is the understanding that imagination is not synonymous with foolishness, and that it is a muscle to be flexed as often as possible. If this key lesson is instilled in children at a young age, we can expect them to become more creative and tolerant adults who in turn raise their own children to view the world as being full of possibilities, as opposed to the frightening monsters we carry with us from childhood. We may find that those monsters hiding in our closets when we’re kids become the unrealized ideas we hide from as adults. Foster’s materializes this concept beautifully and offers adult viewers the opportunity to live vicariously through each imaginary friend we meet.

Foster’s appeals to kids as it depicts authority figures in a patronizing light, such as the uptight Mr. Herriman, who happens to be a huge rabbit (and also reminds me of the androgynous and high-strung Rabbit of Winnie the Pooh). And yes, most of the friends we follow on the show are males. However, these are forgivable offenses considering the lightheartedness the show promotes, not to mention its celebration of childhood and the endless possibilities of the imagination. Madame Foster’s home offers childhood friends a second chance, proving that imaginary friends don’t die or disappear but are lovingly passed on to the next child who is in need of a wacky companion. Child viewers who actually entertain imaginary friends can easily find some validation in this show’s exploration of that thin line that separates reality from make-believe. Foster’s is a fantastic wonderland for young viewers and a gentle push to adults to pay attention to their child’s imaginary friend, who is always very real for the child.

Note: Season one of Foster’s is currently available on Netflix.

______________________________________

Jenny holds a Master of Arts degree in English, and she is a part-time instructor at Alvernia University. Her areas of scholarship include women’s literature, menstrual literacy, and rape-revenge cinema. You can find her on WordPress and Pinterest.

Sailor Moon/Usagi Tsukino:

Sailor Moon/Usagi Tsukino: Sailor Mercury/Ami Mizuno:

Sailor Mercury/Ami Mizuno: Sailor Mars/Rei Hino:

Sailor Mars/Rei Hino:

Sailor Venus/Minako Aino:

Sailor Venus/Minako Aino: Sailor Chibi-Moon/Chibiusa Tsukino:

Sailor Chibi-Moon/Chibiusa Tsukino: Sailor Pluto/Setsuna Meioh:

Sailor Pluto/Setsuna Meioh: Sailor Uranus/Haruka Tenoh:

Sailor Uranus/Haruka Tenoh: Sailor Neptune/Michiru Kaioh:

Sailor Neptune/Michiru Kaioh: