Tag: Objectification of Women

Guest Writer Wednesday: Sucker Punch

Sucker punched by “Sucker Punch”– Girls and guns don’t equal female empowerment

This is a cross-post from What Tami Said.

This really is the best movie ever cuz its like hollywood finally said to me Fuk yeah you my man are all we care about heres some awesome shit for you to get off on and everyone else can just go fuk themselves and you get to watch. Read more…

…it’s the fantasy of a 14-year-old boy steeped in kung fu, “Call of Duty” and online porn. Read more…

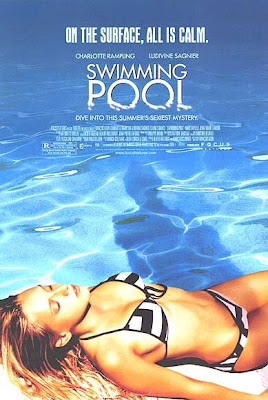

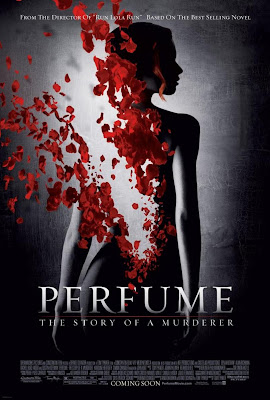

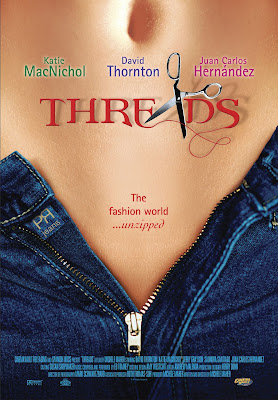

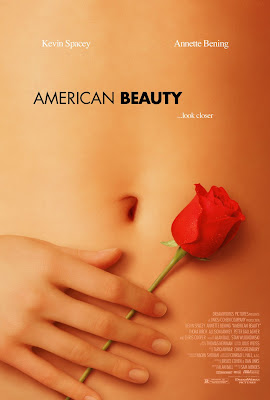

Seriously? These Are the 40 Greatest Movie Posters?

Movie Preview: Bad Teacher

Our 3-Year Blogiversary!

|

| Dolly Parton, Lily Tomlin, and Jane Fonda plot their revenge in 9 to 5 |

- Donate via PayPal. Notice the “Donate” tab at the top right of the page. If you’re a reader who supports what we do, consider donating to the cause. Any amount, however small, is a gesture of support and will help pay for our expenses.

- Purchase items through our Amazon store. We sometimes link to products on Amazon in our posts, and have a widget in our sidebar called “Bitch Flicks’ Picks.” If you go on to make purchases through our site, we earn a small percentage of the proceeds, and if it’s an awesome feminist film, TV show, or book–then we all win.

If you support what we do but can’t afford the financial contributions, there are a number of things you can do to show your appreciation and help spread the word about Bitch Flicks.

- Like our Facebook page and share it with your friends

- Follow us on Twitter

- Subscribe to our RSS feed, or subscribe to posts via email

- Follow us with Google Friend Connect

- Comment on posts

- Contribute a review, analysis, or other related piece (we’re open to original and cross posts)

- Keep reading!

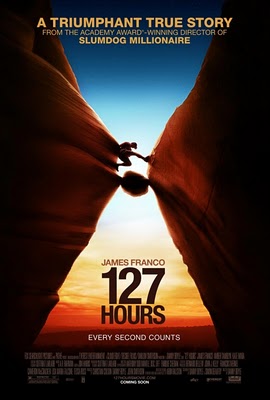

Best Picture Nominee Review Series: 127 Hours

The rest of the movie takes place in the canyon–a claustrophobic nightmare that only works because Franco is apparently an amazing actor–and inside Franco’s mind, through flashbacks of his super hot (gasp) blond ex-girlfriend and the phone calls from his mom and sister that he clearly stupidly ignored prior to his departure. He also hallucinates some crazy shit, like a giant Scooby-Doo blowup doll that’s soundtracked to that ghoulish laughter reminiscent of the last few seconds of Thriller. Yeah! And though it sounds absolutely insane, it’s why the film works. Boyle takes a narrative about a guy struggling to get out of a hole and turns it into an action film, a radio show, a documentary, a commercial, a disaster movie, a cartoon, and a comedy. About a guy struggling to get out of a hole.

Not that there aren’t a few impossible-to-deal-with moments. The final scene, which is poignant enough on its own, insists on beating the audience over the head with its call to EXPERIENCE EMOTION, courtesy of this ridiculous Dido & A.R. Rahman song. And I still can’t quite figure out how the closeup shots of ice-encased Gatorade and Mountain Dew add anything more than advertising revenue, as much as I’d like to argue that, “If I were trapped in a cave, about to die, drinking my own urine, toying with the idea of amputating a limb, I’d totally hallucinate all these brand-name beverages from Pepsico.”

And yes, god, seriously, The Women. I know this is a movie about Ralston’s journey. I respect that and enjoyed watching the innovative ways Boyle used split screens, reverse zooms, fantastical elements, warped focus, and speed variations to tell Ralston’s story in a way I can’t imagine another director successfully telling it. That doesn’t mean I could ignore my own cringing every time a woman entered the frame. The ex-girlfriend clearly serves as a vehicle to show Ralston’s loner-ness; see, he pushed her away all cliche-like. We know this because she says Very Important Things to him. “You’re going to be so lonely,” she yells, after he silently (but with his eyes!) asks her to leave a sporting event they’re attending. (I want to say hockey?)

His hallucinations suck, too. His sister shows up in a wedding dress. His sister showing up in a wedding dress clearly serves as a vehicle to make us feel bad that he’ll be missing Very Important Life Events if he dies, like his sister’s wedding. More pointlessly, the hallucinated sister, who might have one speaking line if I’m being generous, is played by Lizzy Caplan, an actress who’s had large roles in True Blood, Party Down, Hot Tub Time Machine, Cloverfield, and Mean Girls. Instead of engaging with the film, I found myself taken completely out of it, as I wondered why they would cast an actress who’s clearly got more skills than standing in a wedding dress, looking sullen and disappointed, to stand in a wedding dress looking sullen and disappointed.

So, the first two women (the lost ones) show Ralston’s carefree coolness. The ex-girlfriend illustrates Ralston’s darkness and his need for independence–as do the voicemails he ignores from his mother and sister, which are played in flashback. His sister reminds the audience that Ralston has Things to Live For. Hell, Ralston even tries to console his mother in advance (when he records his deathbed goodbye with his video cam) by saying things like, “Don’t feel bad about buying me such cheap, crappy mountain climbing equipment Mom … I mean, how were you supposed to know this would happen!” Hehe. What? Apparently it’s easier to use every possible cliche ever of how men and women interact (as a way to reveal information about the hero’s personality and psyche) than it is to, I don’t know, show him interacting with some guys? Have him flashback-interact with Dad? Nope, we get Lost Women in Need, Wedding Dresses, and Mommy Blaming. And I haven’t even gotten to the masturbation scene yet.

[This is your Spoiler Alert.]

I struggled with the masturbation scene. Because it’s a failed masturbation scene. I mean, it’s a scene where masturbation is attempted unsuccessfully. I didn’t like that he took out his video camera and freeze-framed and zoomed in on a woman’s breasts from earlier–as far as I’m concerned, there’s no other way to look at that than as classic Objectification (and dismemberment) of Women. (Also, the audience laughed, and I was taken out of the film yet again.) But at the same time … whoa. Ralston knows he’s about to die. He’s out of water. He’s got no hope of being rescued. Ultimately, masturbation for him is an act of desperation, the desire to feel something that his body has already let go of. Yes–it’s powerful stuff. Watching Ralston’s body betray him shows his imminent physical death.

But it felt too much like The Ultimate Betrayal. As much as I sympathized with Ralston–and Franco is brilliant in this scene–I don’t want to let the film off the hook entirely. I mean, what’s with men and their dicks? If I’m trapped down there, I’m thinking, “A little less masturbation, a little more amputation.” Honestly. The scene played too much like a metaphor for his final loss of power (read: masculinity), as impotence usually does on-screen. In that moment, I no longer identified with the film’s initial overarching theme of hope and possible redemption; I just thought, “Oh man, he can’t get it up it. SNAP.” I guess I’m just wondering if the film really needed to go there …

So, aside from the women “characters” being cliched, pointless, slightly offensive insertions used only to further our understanding of Ralston, 127 Hours is a fabulous film. I’m not even being sarcastic. I’ve never been much of a Franco fan–I mean, apparently he’s teaching a class about himself now?–but this performance is a game-changer for James and me. Boyle certainly showed his directing chops, too; this movie goes places a viewer would never expect–in fact, I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything like it. I cried. I eye-rolled. I looked away (often). And I laughed. Especially at the end of the film, when the woman behind me said, “Wait. You mean that shit was a true story?!”

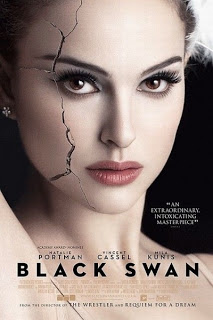

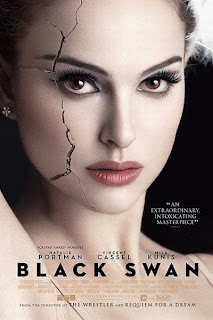

Review in Conversation: Black Swan

|

| Nina is cracking… |

Amber’s Take:

There’s a lot to say about Black Swan, and the more I think about it, the fewer definitive, and perhaps positive things I have to say. Before getting too ahead of myself, though, I must say that the performances–particularly Natalie Portman’s–were amazing, the dance sequences were compelling and seemed very well done, and the film was, overall, visually stunning. This is the most intensely visceral film I’ve seen in some time, and simply remembering certain moments still causes me to cringe. I loved the image of the goose flesh appearing on Nina Sayers’ (Portman’s) skin, as she began to physically embody her role as the Swan Queen, and the nod to Cronenberg’s The Fly when thick, black feathers began to sprout from Nina’s skin (as the hairs sprouted from Jeff Goldblum’s Seth Brundle during his physical transformation into, well, a fly).

On a literal level, the film seems to be about the transformation of an artist–in this case, a dancer–into a role. It also is, very specifically, about the physical rigor of ballet, and the lengths an artist will go to in perfecting her performance. Ballet is a physically grueling art form that seems diametrically at odds with the female body. Like gymnasts, from what I understand, a ballet dancer must fight against a mature woman’s body, maintain an impossibly thin-yet-strong physique, and endure at times severe physical pain. On a more metaphoric level, this is what society expects all women to endure, though I don’t think we can read the white swan/black swan as a direct metaphor of the virgin/whore dichotomy or expectation for women in our culture. There are several other things going on in the film, one of the most problematic being (s)mother love.

What on Earth is Barbara Hershey’s character doing in this film? In a near-deranged, over-the-top role, we see a woman who couldn’t make it out of the corps during her own ballet career, and who blames her daughter for the unhappy end to that career. Erica Sayers infantalizes her daughter, dominates her life, pummels her with guilt for under-appreciating her (the cake scene, anyone?), and generally serves as the movie’s biggest villain–worse than an artistic director who sexually assaults and torments Nina. Oh, that’s nothing compared to Mommy Dearest. So what do we make of Nina’s mother–and why was she even in this movie?

Stephanie’s Take:

While I share some of your concerns with (s)mother love, and Barbara Hershey’s character in general, I really enjoyed the film. So before I respond to some of the issues you mention, let me say what I liked so much about Black Swan:

First, a fairly obvious but no less interesting way to read the film is as an indictment of prescribed femininity. Nina’s entire existence is wrapped up in an attempt to be perfect, whether it’s striving to be the perfect ballerina or the perfect daughter. We see what her breakfast looks like, grapefruit and a hardboiled egg (if I remember correctly), and as you mention, the struggle to maintain a child’s body resonates throughout. While that may be particularly important for careers in ballet and gymnastics, it’s also our society’s ideal body type for all women, so I very much like that Black Swan delves into (however metaphorically) the potential consequences of restrictive and unattainable “perfection” in women.

When Nina can’t live up to the casting director’s Perfect Ballerina or her mother’s Perfect Daughter, she basically loses her shit. Thomas (the casting director, played by Vincent Cassel) wants her to embrace her sexuality, to seduce the audience with it (channeling the Black Swan). Erica (her mother) wants her to remain childlike and innocent (channeling the White Swan), and both Thomas and Erica represent the double-edged sword that all women face: be sexy, but not slutty; be sweet, but not a total prude. In the words of Usher, “We want a lady in the street but a freak in the bed.”)

When Nina can’t fulfill both these roles simultaneously, as much as she tries, the film shows us her breakdown: her body betrays her in literal ways, with bleeding toes and scratch marks that suggest self-mutilation (another hallmark characteristic of young women struggling to cope with similar stress); and her body betrays her in ways that suggest hallucinations: pulling “feathers” from her flesh, or ripping off her cuticles, only to discover moments later that her hand is fine. I found that part of the film, the hallucinatory transformation into the Black Swan, super interesting because it seems to happen to her accidentally—as she experiences the transformation, she doesn’t understand what’s happening, and it frightens her.

In fact, I would argue that her body isn’t her own at any time during the film. Thomas wants to control her body in a sexual way, often groping her and kissing her against her will. And when Nina attempts to explore her sexuality, to take ownership of it through masturbation, she suddenly realizes her mother is in the room (to the gasps and laughter of audiences nationwide), and she buries herself under her covers like a child. Erica constantly explores Nina’s body either by looking at her or physically touching her, often insisting that she remove her clothes—creating an inappropriateness in their relationship that I don’t quite know what to do with.

Regardless, I like that Black Swan implies that these ideals for women can’t actually exist without women destroying themselves in the process of attaining them. We live in a society where women’s bodies exist as pleasure-objects for men, as dismembered parts to sell products, as images to be dissected, airbrushed, made fun of, all under a government that continues to chip away at women’s rights to bodily autonomy. In that kind of environment, when does a woman’s body ever feel entirely her own? Black Swan sets up that metaphor quite well, asking the viewer to experience Nina’s struggle to live up to society’s ridiculous expectations for women through several cringe-worthy moments.

That rocks. But I wonder if that effort gets trumped by some of the more objectifying scenes, like the “lesbian sex scene” and the masturbation scene. Is it possible to comment on society’s expectations of women and beauty without also objectifying women in the process? Does Aronofsky linger a little too long at times? And, in response to your second paragraph, why can’t we read the Black Swan/White Swan as a direct metaphor for the virgin/whore dichotomy? (Oh, and yeah, I’ll throw it back to you—what the hell is happening with Nina and her mom?)

Amber’s Take:

You make a lovely and convincing reading of the film as an exploration of the impossibility of society’s contemporary take on womanhood. I think my resistance to this reading—or, more specifically, my dissatisfaction of this being the ultimate reading—has everything to do with Erica Sayers, though neither of us is certain how to exactly read her character. More on that in a moment (ha ha). Though meaning doesn’t end (or begin, necessarily) with a director’s intention, I also think this reading gives Aronofsky too much credit; in other words, I don’t know that the film is that good—that altrustic, that interested in women’s experience—or that cohesive.

Aronofsky has a clear interest in the limits of the human body. While watching Black Swan, I thought about his previous movie, The Wrestler, and the ways in which that solitary person pushes his body to limits most us of (those of us who aren’t professional wrestlers or ballerinas) find absurd and painful to even see. We could extend our conversation indefinitely by bringing in other movies as objects of comparison (The Red Shoes

), but I do see some structural similarities between Black Swan and The Wrestler that warrant at least a cursory comparison–and I’m sure others have done this comparative work in reviews around the web.

An important question to ask when we’re trying to figure out Black Swan is this: How do we see Nina Sayers at the end of the film? Is she a victim of her society/mother/creative director? Or is she victorious, in that she conquered the perceived limits of her body to achieve her own stated goal: to be perfect in her Swan Lake performance. (Did we see the protagonist of The Wrestler as victorious or defeated in his final leap?) Nina masters her performance, nailing the Black Swan to the point she imagines her arms transforming into wings. This was the most thrilling sequence in the film—her performance was beautiful, and much more impressive than any of the other dance sequences. Is the Black Swan a villain? In the ballet, yes, and the White Swan is the tragic heroine. Films generally tend to do a better job of making the villain more compelling than the hero, but if both roles are (metaphoric) unattainable goals, how do we read those final moments?

It’s not that I disagree with your reading—I really want that to be what the movie is ultimately about, but there are too many half-baked ideas competing with each other to allow me to say Okay, it’s about X. And, frankly, there’s an awful lot of pleasure to be had by gazing at tormented bodies in the film for me to wholly believe its feminist message. Before Nina gets the lead role in Swan Lake she looks hopefully at a woman walking toward her at a distance, and sees herself in the face of a stranger. So, she’s looking for her a reflection of herself, evidence of her own existence in other people. I don’t think this is a statement about a woman’s unstable identity; I think it’s what an artistic performer does. And possibly a person grappling with mental illness. What about Lily (Mila Kunis)? Her cheeseburger, ecstasy, and alcohol-fueled night with Nina, leading to empowered club dancing (sarcasm), random dude-kissing, and imagined sexy lesbian action between the two, does…what, exactly? Neither the skeezy artistic director’s advice (masturbate!) nor San Francisco Lily’s trite transgressions work to sexually liberate Nina…or do they? At least they bring her into active conflict with her mother.

Now. Nina lives with a mother who is basically a lunatic. I mean, let’s just say it: Nina’s mother is fucking nuts. Why (in the world of the film) does Nina need to have a mother who is fucking nuts? Couldn’t she have been moderately nuts, like most of us, with contradictions, who acts in moderately selfish ways which can moderately mess up a daughter? That would’ve allowed the themes we’ve discussed to be played out just as intricately and interestingly. How does this character fit into the movie? Taken literally, Nina’s mother is at fault for her child’s problems. As mothers tend to be in films made by men, and as psychiatrists believed in the 1960s (I’m thinking of the concept of the schizophrenogenic mother here–the idea that an oppressive mother could actually cause schizophrenia in her children). While we might be seeing a version of Erica Sayers from Nina’s untrustworthy perspective, what good is it—even if it’s not an accurate representation—for Nina to see her mother this way? Taken metaphorically…what? There’s no feminist reading I can discern in a film that I want to be feminist.

Stephanie’s Take:

I completely agree that it might not be useful, or even possible in a film as complicated as Black Swan, to come up with a definitive reading. But I still believe so much is at stake with regards to women and identity and the fluidity of that identity, in a culture that forces women to possess multiple, often contradictory identities. Maybe I’m giving Aronofsky too much credit, but I disagree with your suggestion that Nina’s literal reflections aren’t a statement about a woman’s unstable identity.

Yes, this film comments plenty on the artist and how performance can impact an artist’s life, how the artist must take on certain traits to enhance her performance, and how that act might impact her life when she isn’t on stage. However, given the fact that we’re all “performing” our identities to an extent (like the prescribed gender roles we’re taught from birth to perform), it’s worth looking at how Nina, a character whose identity seems so wrapped up in the expectations of those around her, copes—or doesn’t cope—with the pressures of womanhood and what’s required of that particular role.

It’s impossible not to notice Nina’s reflection everywhere. She sees herself reflected in mirrors as she dances, or when she’s reading the word “whore” on the bathroom mirror of the dance studio, or when she sees her face in the subway car windows. And as you mentioned, she sees her face superimposed on the faces of strangers in public—and even in the mirror at her own house, where she and Lily’s faces are superimposed.

It happens again during the sex scene; Lily’s face becomes Nina’s own face at one point, and we can hear Lily creepily whispering the words of Nina’s mother, “my sweet girl” over and over. Since we learn later that this sex scene is most likely Nina’s hallucination (and I think there’s enough evidence to even make the argument that Lily’s entire existence is a hallucination), it’s useful in interpreting the film to think about why Nina sees Lily, hears her mother’s words, and even sees her own image during a sex scene.

All this swapping of voices and faces (identities, if you will, haha) lead me to read all these people, Erica, Beth (Winona Ryder), and Lily as facets and projections of Nina’s identity. Beth, Thomas’s first “little princess,” is the aging ballerina who gets replaced by Nina, the younger ballerina. Erica, her mother, is the ballerina who slept with her director, got pregnant, and had to end her dancing career as a result. And Lily is the ballerina who embodies everything Nina tries so desperately to find within herself. She’s a carefree, sexual woman who repeatedly threatens Nina’s role in the ballet. Both when Nina is late to rehearsal and when Nina is late to the show’s opening—Lily stands in the background, threatening to take Nina’s place.

Keeping that in mind, it’s interesting that Nina “murders” Lily; on one hand, Nina seeks to absorb Lily’s empowerment, but on the other, the only way she can ultimately accomplish that is by killing it. Since murder is a pretty empowered act, I guess I get that. In fact, I think I liked it. Because Nina basically says Fuck You to the idea that Lily, who represents Nina’s unattainable sexual identity, is separate from herself, her whole self. In that moment, Nina transforms fully into The Black Swan, allowing Lily’s metaphoric death to push Nina to do what she previously thought herself incapable of accomplishing.

You argue that the alcohol-fueled, “imagined sexy lesbian action between the two” does nothing to really sexually liberate Nina. I struggled with this scene in the film probably more than any other scene because it feels exploitative and objectifying in the same way most Hollywood faux-lesbian sex scenes do. But I also believe it’s important to pay attention to all the stuff I mentioned previously. There’s tons of identity-shifting in this scene. Nina’s eventual sexual liberation (if we equate her successful transformation into the Black Swan with sexual liberation) begins here; when identities become interchangeable in this scene, we get the first images of the gooseflesh appearing on Nina’s skin. Something empowering seems to be happening. Whether it’s actual sexual liberation or the first signs of Nina embracing all these facets of herself (Beth, Erica, Lily), it complicates things. But what does it mean?

Well! I’ll go back to my original argument: Black Swan implies that these ideals for women can’t actually exist without women destroying themselves in the process of attaining them. How many identities can we effectively perform before we forget entirely who we are? Women struggle with that in a way that men never will. More often than not, it’s women who have to give up careers for children (Erica). They get pushed out of their professions when they get older (Beth). They’re expected to balance innocence with sexuality and to know when (and when not to) express them (Nina/Lily). And the attempt to balance, express, and suppress these prescribed roles often doesn’t work without having a detrimental impact on women individually and as a whole.

Interestingly, Nina and Lily both “die” in the end. So women in this film end up visibly crazy, hospitalized, or dead. In a less complex film, that would seriously piss me off. But the death and/or disappearance and/or insanity of these women make a larger point: if they’re all separate facets of Nina’s own personality and identity, which I believe they are, it’s necessary to watch each separate character struggle—it reinforces the idea that these performed identities aren’t possible without sacrificing one’s entire self.

You asked: If the Black Swan/White Swan “roles are (metaphoric) unattainable goals, how do we read those final moments?” Good question. It fascinates me most of all that Nina claims, after the White Swan’s suicide, that her performance was perfect. But, it wasn’t. She fell down in the middle of the damn ballet. To a gasping and appalled audience (not to mention, director). If her “I was perfect” claim applies only to the ballet, then she’s referring only to her performance as the Black Swan; after all, it’s the Black Swan whose dance partner whispers “wow” as she’s walking off stage; it’s the Black Swan whose audience gives her a standing ovation; it’s the Black Swan whose director beams with pride when she leaves the stage.

So yeah, I see Nina as a victim at the end of the film. Because she wasn’t perfect; she was never perfect. The conquering of her role as the Black Swan comes at a great sacrifice to her role as the White Swan (her fall during the ballet and her metaphoric death at the end of it). The two identities can’t coexist perfectly, as much as she wants them to. In the end, she still hasn’t attained the superhuman ability to perform competing identities for a critical audience. Sure, the audience may have loved Nina’s empowered, sexualized Black Swan, clearly enough to forgive the earlier screw up as the White Swan, but that isn’t surprising if you read the audience as a metaphor for society (why not?), a society that loves more than anything to be seduced by its women.

——————————-

We still have more to say! Let the conversation continue in the comments section, and leave links to reviews you’ve written or read.

Disembodied Women Take Five: Mouthing Off

Disembodied Women Take Four: … Look Closer

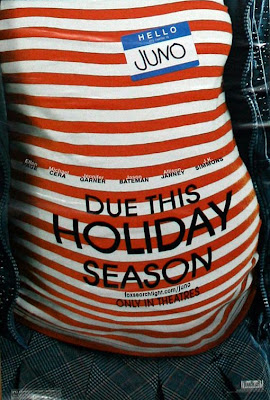

As if reducing women to a collection of nothing more than unrealistically portrayed body parts weren’t enough, the accompanying taglines of these particular film posters also caught my attention.

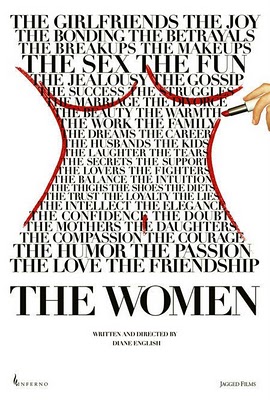

The Women and 27 Dresses don’t use a catchy tagline on the posters shown below. Maybe the designers of the posters felt that random words shaped into a woman’s torso would suffice, considering these two films exclusively target women audiences. And what do audiences comprised of women want to see in The Women? Nouns, apparently: Bonding Joy Jealous Kids Tears Struggles Laughter Thighs Balance Intuition Fighters Passion Elegance Shoes …

With the 27 Dresses poster, what else could we possibly need? She’s already been made into a fucking dress. (Get it? The movie is called 27 Dresses, so Katherine Heigl’s body is like totally a dress. Neat! Way to objectify a woman by turning her into an actual object.)

The other two posters depicting a pregnant woman each emphasize two men, the first one showing two men in a photo, and the other showing two men smiling ridiculously while cradling the woman’s stomach. Also note the … what, shaving cream smiley face? … painted on her stomach.

Then the taglines.

In Misconceptions, we get: “Good things come in other people’s packages.” Um, okay. Whose “package” are they referring to here exactly? The woman-as-baby-making-machine who will deliver a package in nine months? Or one of the two men apparently involved in providing sperm? With his … package? What the hell is happening here.

In the poster for The Brothers Solomon, they just come out and say it: “They want to put a baby in you.” Great! A film about a woman’s pregnancy that’s actually somehow about two men. Thanks, Hollywood.

The remaining posters that incorporate taglines:

Tomcats: “The last man standing gets the kitty.”

Swimming Pool: “On the surface, all is calm.”

Threads: “The fashion world … unzipped.”

American Beauty: ” … look closer”

The Babysitters: “These girls mean business.”