Tag: Objectification of Women

Bitch Flicks’ Weekly Picks

“Tilda Swinton: I Didn’t Speak for Five Years” by Kira Cochrane for The Guardian

“Are TV Ads Getting More Sexist?” by Derek Thompson for The Atlantic

“Painful Baby Boom on Prime-Time TV” by Neil Genzlinger for The New York Times

“The Rebirth of the Feminist Manifesto” by Emily Nussbaum for New York Magazine

“Sexy or Sexism? Redefine Sexy, Identify Sexism” from SexyorSexism.org

“Diverse Black Women Dominating Daytime TV” by Ronda Racha Penrice for The Grio

“Chapstick Sticks It to Women” by Melissa Spiers for ReelGirl

“‘How to Be a Gentleman'” Cancelled” by James Hibberd for Entertainment Weekly

“Is She Really With Him?” by Molly McCaffrey for I Will Not Diet

“We’ll Always Be Together: Girl-Gang Style in Movies” by Marie for Rookie Magazine

Here’s the part where we ask for your help.

- Donate via PayPal. Notice the “Donate” tab at the top right of the page. If you’re a reader who supports what we do, consider donating to the cause. Any amount, however small, is a greatly appreciated gesture of support and will help pay for our expenses.

- Purchase items through our Amazon store. We have a widget in our sidebar called “Bitch Flicks’ Picks.” If you go on to make purchases through our site, we earn a small percentage of the proceeds, and if it’s an awesome feminist film, TV show, or book–then we all win.

If you can’t afford a financial contribution, there are a number of things you can do to help.

- Like our Facebook page and share it with your friends

- Follow us on Twitter

- Subscribe to our RSS feed

- Subscribe to posts via email

- Follow us with Google Friend Connect

- Stumble our posts

- Comment

- Contribute a review, analysis, or other related piece (we’re open to original and cross-posts)

- Keep reading!

Horror Week 2011: The Sexiness of Slaughter: The Sexualization of Women in Slasher Films

Over the course of the series’ eight one-hour episodes, those skilled and sexy enough to command the screen survive. Those who don’t will “get the axe” until only one strong, seductive and stellar actress remains, earning the break-out role in “Saw VI” and the title of Scream Queen.

The season 1 winner, Tanedra Howard, won the chance to show audiences just how seductive and stellar she could look while being tortured.

As years passed, young audiences required that gruesome images become more intense and explicit for them to become scared…In 1978, a movie called Halloween not only sold more tickets than any other horror film, it broke all previous box-office records for any type of film made by an independent production company. Hollywood immediately tried to tap into the success of Halloween. Films such as Friday the 13th, Don’t Go In the House, Prom Night, Terror Train, He Knows You’re Alone, and Don’t Answer the Phone were all released in 1980. These movies, which are some of the first slasher films, were extremely successful. However, with their increasing popularity came strong criticism. Slasher films were condemned for frequently portraying vicious attacks against mostly females and for mixing sex scenes with violent acts.

This popular kill from Jason X involves scientist Andrea getting her face dunked in liquid nitrogen. While struggling with Jason, Andrea’s shit (half of what could be a sexy scientist Halloween costume) rides up revealing to the audience the bottom of her full breasts. While this small glimpse does not equate itself to the arousal of an all-out sex scene, it is intentional. From costuming to blocking, every aspect of the character’s femininity in this scene was meticulously plotted. The fact that filmmakers, audiences, and Maxim find a kill scene more enticing if the woman is sexy and almost shirtless speaks to the fact that modern horror films sexualize slaughter.

Social scientists have expressed concern over the negative effects that slasher films may have on audiences. In particular, exposure to scenes that mix sex and violence is believed to dull males’ emotional reactions to filmed violence, and males are less disturbed by images of extreme violence aimed at women (Linz, Donnerstein & Adams, 1989). These effects on male viewers are said to derive from “classical conditioning”.

Sapolsky and Molitor rebuff this idea, believing that the pairing of sex and violence does not occur often enough for classical condition to occur. However, they further state:

The concern over potential negative effects of exposure to slasher films remains. Possibly, depictions of violence directed at women as well as the substantial amount of screen time in which women are shown in terror may reduce male viewers’ anxiety. Lowered anxiety reduces males’ responses to subsequently-viewed violence, including violence directed at women. Accordingly, the desensitizing effects of slasher films may result from a form of “extinction” and not from classical conditioning.”

It appears that no matter how you slice it, this pairing, on unconscious level, does not leave viewers unaffected.

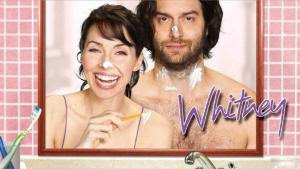

Ripley’s Rebuke: ‘Whitney’ versus Whitney

|

| Even the promo shots for Whitney attempt retro, but come off as regressive. |

Quote of the Day: Judith Mayne

|

| Directed by Dorothy Arzner by Judith Mayne |

In the early to mid-1970s, when Arzner’s work was brought to the attention of feminists, her films were deemed particularly important for their criticism of Hollywood films “from within.” Pam Cook and Claire Johnston described how the universe of the male was “made strange” in Arzner’s films, how women’s “rewriting” of male discourse subverted the established conventions of Hollywood. At the time Cook and Johnston’s essays were published, film theory was very much preoccupied with the notion of “making strange,” with the possibilities of a Hollywood film that critiqued itself and its own assumptions. Cook and Johnston brought a strong theoretical approach to Arzner’s work, while other critics of the era were simply delighted to find a woman director among all of the men in Hollywood film history.

The plot of Dance, Girl, Dance concerns the differing paths to success for Bubbles (Lucille Ball) and Judy (Maureen O’Hara), both members of a dance troupe led by Madame Basilova (Maria Ouspenskaya). The dance troupe performs vaudeville-style numbers in bars and nightclubs, much to the chagrin of Basilova (who bemoans her status as a “flesh peddler”). Bubbles has “oomph,” a kind of dancer’s version of “it,” and eventually she leaves the troupe and enthusiastically pursues a career as “Tiger Lily White.” Judy, in contrast, is a serious student of ballet, and the protegee of Basilova. However, it is Bubbles who gets the jobs, and she arranges for Judy to be hired as her “stooge,” i.e., as a classical dancer who performs in the middle of Bubble’s act, and thus primes the audience to demand more of Bubbles.

Toward the end of the film, Judy stands on stage and refuses her role as stooge. She defiantly crosses her arms and moves closer to the audience, and she gives the spectators a piece of her mind:

Go ahead and stare. I’m not ashamed. Go on. Laugh! Get your money’s worth. Nobody’s going to hurt you. I know you want me to tear my clothes off so’s you can look your fifty cents worth. Fifty cents for the privilege of staring at a girl the way your wives won’t let you. What do you suppose we think of you up here–with your silly smirks your mothers would be ashamed of? And we know it’s the thing of the moment for the dress suits to come and laugh at us too. We’d laugh right back at the lot of you, only we’re paid to let you sit there and roll your eyes and make your screamingly clever remarks. What’s it for? So’s you can go home when the show’s over and strut before your wives and sweethearts and play at being the stronger sex for a minute? I’m sure they see through you just like we do.

I see Judy’s confrontation less as a challenge to the very notion of woman as object of spectacle than as the creation of another kind of performance. Oftentimes the scene is discussed as if the audience were exclusively male, which it is not, even though Judy addresses men in her speech. When the camera pans the reactions of the audience to Judy’s speech, the responses of women are quite clearly visible. Women squirm uncomfortably in their seats just as surely as men do, and when release occurs in the form of applause, it is a woman–Steven Adams’s trusty secretary–who initiates it. Arzner’s view of performance and her view of the relationship between subject and object were never absolute; women may be objectified through performance, but they are also empowered; men may consume women through the look, but women also watch and take pleasure in the spectacle of other women’s performance.

Thoughts?

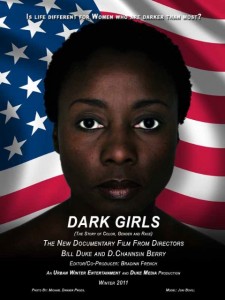

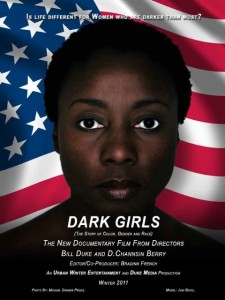

Documentary Preview: Dark Girls

|

| Dark Girls (2012) |

Writing for Clutch, Jamilah Lemieux says:

While many people would love to believe that color is no longer an issue, and that we are post-racial, post-color struck–post-anything that forces them to admit that all things are not even in this world, and that we have much work to do–the many subjects interviewed for the film sing a very different tune.

[…]

Though we know that not all darker sisters suffer great indignities or issues with self image, nor is life a crystal stair for those of us who are lighter, this film continues a long conversation that is still very important. So long as we have people amongst us who gladly uphold the damning “White is right” standard–assigning favor to people based upon their proximity to it, we can’t let this one go. This is something we can get past, this does not have to continue.

Watch the trailer and share your own experiences on the official film website:

Bitch Flicks’ Weekly Picks

Rachel Maddow Reviews ERA History from Gender Focus

July Movies I Won’t Be Seeing (And One I Will) from The Funny Feminist

Pop Pedestal: Captain Turanga Leela from Bitch Magazine

Help Expose the Real Illusionists from Adios Barbie

The Idiot Box Goes Back to the Future from The New Agenda

Great Sites About Women in the Media I Had to Share from BlogHer

Talk to John Carpenter on Twitter on Friday, July 8th from Flick Filosopher

Feminist Booster Club: Help a Native Filmmaker Finish Her Doc on LaDonna Harris from Ms. Magazine

Pissed Off in a Huge Way from FBomb

HBO, You’re Busted from the Los Angeles Times

Leave your links!

YouTube Break: Jean Kilbourne’s "Killing Us Softly" Lecture

From her website:

Jean Kilbourne, Ed.D. is internationally recognized for her pioneering work on the image of women in advertising and her critical studies of alcohol and tobacco advertising. Her films, lectures, and television appearances have been seen by millions of people throughout the world. She was named by The New York Times Magazine as one of the three most popular speakers on college campuses. She is the author of the award-winning book Can’t Buy My Love: How Advertising Changes the Way We Think and Feel and co-author of So Sexy So Soon: The New Sexualized Childhood and What Parents Can Do to Protect Their Kids. The prize-winning films based on her lectures include Killing Us Softly, Spin the Bottle, and Slim Hopes.

Guest Writer Wednesday: The Hollywood Concept of Collateral Beauty

|

| Emily Deschanel |

On the other hand, women are doing quite well on The Good Wife, where the estimable Julianna Margulies creates a memorable woman with a few spare brushstrokes. Her riveting understatement is ably complimented by two other remarkable women, Christine Baranski and Archie Panjabi.

|

| Julianna Margulies |

It’s to the great credit of actresses like Stephanie March, Diane Neal, Marg Helgenberger, Emily Procter, Mariska Hargitay and quite a few others that their presence transcends the weak hands they’re dealt by directors, writers and producers. They illuminate their series in spite of the best intentions of the director to contain them. March, for instance, in episode after episode of Law and Order stood out from the ensemble because of her gravitas and aura of integrity. As for Helgenberger, the camera celebrates her no matter what hand the producers deal her. And who wouldn’t rather follow Procter into the jaws of hell than the show’s star, the one-note David Caruso? The same may be said for reserved Alana de la Garza, who first appeared in CSI: Miami, went on to Law and Order in New York and now plays in its spin-off, Law and Order: LA.

|

| Mary McCormack |

If we truly wanted to be a great nation the filmmakers could lead the way. But first they must acknowledge that the Marlboro Man could be a boob, his looks being no warranty of anything but Big Tobacco’s preconceptions, Anglo-centrism and misogyny.

The Grass is Not Always Greener: On Body Image and Illness

Guest Writer Wednesday: Girl Power in Sucker Punch, Hanna, and Winter’s Bone

Sucker Punch (directed by Zack Snyder) left me with a knotted feeling in my stomach, as well as with conflicted emotions. I loved the idea of a character escaping her reality of abuse and institutionalization by folding within herself and locating a place of refuge deep in her subconscious. Whatever was happening to her body in real life, her mind was not aware of it because she was in another realm—a more powerful one. I didn’t like that she escaped the reality of a mental institution and an impending lobotomy into a brothel where the girls were being sold off to men. A girl would not escape to this kind of world out of choice, even if she knew she was going to be lobotomized at the end of her journey. And to suggest that sex-trafficking is better than a lobotomy is insane in itself—lobotomize me any day of the week. To have her find refuge into a brothel was definitely an attempt at appeasing the men in the audience of this film. It would not appeal to women. What did appeal to me was that I did not have to watch this beautiful girl gyrate and dance provocatively in order to seduce the highest paying john—who of course, is an old, fat, cigar-smoking and money-padded man with power and political standing.

Sucker Punch (directed by Zack Snyder) left me with a knotted feeling in my stomach, as well as with conflicted emotions. I loved the idea of a character escaping her reality of abuse and institutionalization by folding within herself and locating a place of refuge deep in her subconscious. Whatever was happening to her body in real life, her mind was not aware of it because she was in another realm—a more powerful one. I didn’t like that she escaped the reality of a mental institution and an impending lobotomy into a brothel where the girls were being sold off to men. A girl would not escape to this kind of world out of choice, even if she knew she was going to be lobotomized at the end of her journey. And to suggest that sex-trafficking is better than a lobotomy is insane in itself—lobotomize me any day of the week. To have her find refuge into a brothel was definitely an attempt at appeasing the men in the audience of this film. It would not appeal to women. What did appeal to me was that I did not have to watch this beautiful girl gyrate and dance provocatively in order to seduce the highest paying john—who of course, is an old, fat, cigar-smoking and money-padded man with power and political standing.  In contrast, I was pleasantly surprised with Hanna, (directed by Joe Wright), which just came out. 16-years-old, Hanna (Saoirse Ronan) is raised by her father, an ex-CIA operative who has taught her everything she knows. We first meet her in the wild forests of Finland, very unsexy, un-pretty, and completely covered in layers. And we find her hunting with a bow and arrow, sprinting after her prey, killing it, and then gutting it with her bare hands. So unsexy, and yet so powerful. A small girl, she is smart, fast, and logical.

In contrast, I was pleasantly surprised with Hanna, (directed by Joe Wright), which just came out. 16-years-old, Hanna (Saoirse Ronan) is raised by her father, an ex-CIA operative who has taught her everything she knows. We first meet her in the wild forests of Finland, very unsexy, un-pretty, and completely covered in layers. And we find her hunting with a bow and arrow, sprinting after her prey, killing it, and then gutting it with her bare hands. So unsexy, and yet so powerful. A small girl, she is smart, fast, and logical.  Which brings us to Winter’s Bone. I rented this movie one Saturday night, and although it has been criticized for its stark and depressing mood, it is real, gutsy, and a true feminist—womanist—girl power-ish film, lacking in pretensions, sexism, or glamor. 17-year-old Ree Dolly (Jennifer Lawrence) is a real-life girl in the real world, born into the “patriarchal male honor culture of the Missouri Ozarks” (James Bowman, 2010), who feeds her siblings squirrels, and teaches her brother how to hunt, kill, skin, and make a meal of it—all lessons a father would teach to his son. But he’s not around. Part of this culture highlighted by drugs and murder, he is missing; her mother is mentally depressed and useless; and Ree is left to tend to her younger siblings and make sure their house isn’t taken away from them. She is cajoled, lied to, threatened, beaten by men and other women in this clan, and she faces the reality of her real-life responsibilities with quiet fortitude. Accepting the fact that her father is dead, it is left up to this girl to find proof of his death in order to keep her parents’ house from being taken away and leaving her and her mother and siblings homeless. She puts her life in danger to accomplish her goal, and she also gives up her dream of escaping this kind of corrupt life by joining the army and making something better of herself and her future. She is able to save her house and family, through sheer nerve and guts, alone, and for this, she is a true hero—a real life heroine that we can feel confident in advocating as strong.

Which brings us to Winter’s Bone. I rented this movie one Saturday night, and although it has been criticized for its stark and depressing mood, it is real, gutsy, and a true feminist—womanist—girl power-ish film, lacking in pretensions, sexism, or glamor. 17-year-old Ree Dolly (Jennifer Lawrence) is a real-life girl in the real world, born into the “patriarchal male honor culture of the Missouri Ozarks” (James Bowman, 2010), who feeds her siblings squirrels, and teaches her brother how to hunt, kill, skin, and make a meal of it—all lessons a father would teach to his son. But he’s not around. Part of this culture highlighted by drugs and murder, he is missing; her mother is mentally depressed and useless; and Ree is left to tend to her younger siblings and make sure their house isn’t taken away from them. She is cajoled, lied to, threatened, beaten by men and other women in this clan, and she faces the reality of her real-life responsibilities with quiet fortitude. Accepting the fact that her father is dead, it is left up to this girl to find proof of his death in order to keep her parents’ house from being taken away and leaving her and her mother and siblings homeless. She puts her life in danger to accomplish her goal, and she also gives up her dream of escaping this kind of corrupt life by joining the army and making something better of herself and her future. She is able to save her house and family, through sheer nerve and guts, alone, and for this, she is a true hero—a real life heroine that we can feel confident in advocating as strong.