|

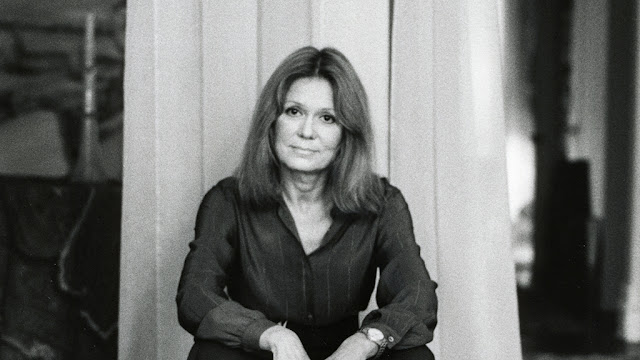

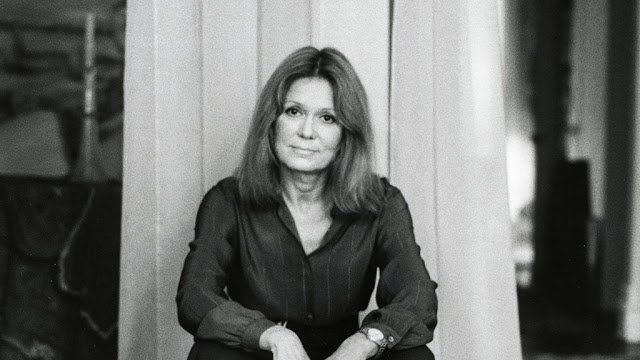

| Gloria Steinem in HBO’s Gloria: In Her Own Words |

If I were to ask you to name a famous feminist, who would you say? I’m going to go out on a limb and guess that most of you would probably say Gloria Steinem. And with good reason. A pioneering feminist icon, she’s been the face of feminism for nearly 50 years. Many people have admired and judged her, putting their own perceptions on who she is. In the documentary

Gloria: In Her Own Words, Steinem tells her own story.

Directed by Peter Kunhardt and produced by Kunhardt and Sheila Nevins, the HBO documentary which also aired at this year’s Athena Film Fest, “recounts her transformation from reporter to feminist icon.” It explores Steinem’s life through intimate interviews and impressive historical footage, focusing on the tumultuous 60s and 70s, the core of the Women’s Liberation Movement. It’s an intriguing and thought-provoking introduction to feminism and insight of a feminist activist.

Gloria: In Her Own Words covers Steinem’s childhood in a working-class neighborhood in Toledo, Ohio and her early career as a journalist. One of her assignments involved going undercover doing an expose on the Playboy Club. Through the unfolding of her history, she discusses gender disparity in wages and sexual harassment. In 1970, women earned half of what men earned. Women were told that they couldn’t handle responsibility or couldn’t maintain the same level of concentration as men. And of course, women were told their place was in the home. She said that if you were pretty, people assumed you got assignments based on your looks. Of course it couldn’t be due to a woman’s intelligence or work ethic. Silly me. Steinem also revealed that her boss sexually harassed her at the Sunday Times. She said:

“There was no word for sexual harassment. It was just called life. So you had to find your own individual way around it.”

Steinem found that she wasn’t alone. Many, MANY other women faced this same barrage of sexism and misogyny. She said she “wasn’t crazy, it was the system that was crazy.” This echoes something badass feminist poet and activist Staceyann Chin said when I attended Feminist Winter Term in NYC last year. Some young women feel like they’re losing their minds, that they see something wrong with society but so many others don’t. I know this is how I felt for a long time. But there’s nothing wrong or weird or abnormal about wanting to be treated equitably. Steinem says:

“I began to understand that my experience was an almost universal female experience.”

Is there a “universal female experience?” I disagree. Yes, many women face the same gendered oppressions and stigmas. But this ignores the intersectionality of sexism, racism, classism, ableism, homophobia, transphobia, etc. that play pivotal roles in women’s lives. But Steinem asserts:

“Women really do have a community of interest because we are relegated to menial and dehumanized positions simply because we’re women.”

While the film glosses over some parts some parts of Steinem’s life I was absolutely thrilled it showcased abortion and reproductive justice. Steinem revealed how she had an abortion when she was 22 which she kept secret. When she covered an abortion hearing in New York in 1969, she realized the importance of reproductive justice. And that was her “click” moment in becoming a feminist:

“Women were standing up and sharing their abortion experiences…I listened to these women testify about all that they had to go through, the injury, the danger, the infection, the sexual humiliation, you know to get an illegal abortion. And I suddenly realized why is it a secret, you know? If 1 in 3 women has needed an abortion in her lifetime in this country, why is it a secret and why is it criminal and why is it dangerous?

“And that was the big click. It transformed me and I began to seek out everything I could find on what was then the burgeoning women’s movement.”

It’s interesting that abortion can be a catalyzing force in declaring a feminist identity. But it makes sense. When the government tries to take away your reproductive rights, to make choices about your own body, you realize the importance your voice and standing up for your rights. And Steinem’s absolutely right; an abortion stigma of shame should not exist. There’s nothing shameful in making a choice about your reproductive health. With the passage of Roe v. Wade and the legalization of abortion in 1973, “reproductive freedom” was established “as a basic right like freedom of speech or freedom of assembly.” Sadly, it’s a war we’re still fighting to win.

For Steinem, becoming a feminist meant becoming part of a group, something she had never felt before. She also discussed the “demonization” of “the word ‘feminist:’”

“I think that being a feminist means that you see the world whole instead of half…It shouldn’t need a name. One day it won’t…

“Feminism starts out being very simple. It starts out being the instinct of a little child who says it’s not fair and you are not the boss of me…and it ends up being a worldview that questions hierarchy altogether.”

As she “realized there was nothing for women to read that was controlled by women,” Steinem recognized the crucial need for feminist media. This sparked the creation of Ms. Magazine, the first feminist publication in 1972, which Steinem co-founded and edited. She said that while they didn’t invent the term “Ms,” it was “the exact parallel to “Mr.” and it had a great, obvious political use.” Marital status doesn’t affect male identity, so why should it affect women’s? Men in the media predicted its rapid demise. Yet it sold out in a week. Thankfully, it’s still in print as it’s one of my fave magazines!

Gloria: In Her Own Words shows footage of Steinem in interviews, rallies, marches and conferences such as the 1977 National Women’s Conference and the 2005 March for Women’s Lives in DC. At a rally for the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), Steinem declared:

“We’ve been much too law-abiding and docile for too long but I think that period is about over. So I only want to remind you and me tonight that what we are talking about is a revolution, and not a reform…

“We are the women that our parents warned us about and we are proud.”

Throughout the film, Steinem talks about anger:

“A woman who aspires to something is called a bitch…There’s such huge punishment in the culture for an angry woman…I learned to use anger constructively.”

Society tells us women are meant to be docile and agreeable, not righteous and angry. As an angry child who grew up to be an angry woman, it was refreshing to hear Steinem discuss this stigma. She also talks about the need to advocate and fight for your rights as “nobody hands you equality.”

Steinem frankly shares her triumphs and her pain. She discussed her friction with feminist Betty Friedan, her admiration for her friend U.S. Representative Bella Abzug, a feminist pioneer, and her alliance with activist Angela Davis. She talks about her regret at distancing herself from her mother and her choice not to have children saying “having children should not be such a deep part of a woman’s identity.” She discussed her marriage to husband David Bale, whom she called “an irresistible force” and who sometimes introduced himself as Mr. Steinem, much to her chagrin. She survived breast cancer, depression and faced her own lack of self-esteem.

While the documentary alludes to Steinem’s other social justice passions, one for me, is glaringly omitted: her passion for animal rights. As a feminist vegan, I often see the two movements bifurcated, despite some of the parallel struggles. So it would have been great to see that here.

Throughout the film, I get the sense that Steinem is intelligent, kind, witty and passionate. When asked if she feels just as strongly today as she did when she started out as an activist, Steinem says:

“Oh much more, god much more, much much more. And it’s a world view. Once you start looking at us all as human beings, you no longer are likely to accept economic differences and racial differences and ethnic differences. So you have to uproot racism and sexism at the same time otherwise it just doesn’t work.”

I love this holistic view of abolishing kyriarchy and multiple systems of oppression.

Feminist writer Amanda Marcotte critiqued the documentary as “

fun” and “worthy” yet “incomplete” and “far too upbeat.” I see her point. Yes, some events, particularly the ERA, were glossed over and some viewers might not understand the full scope of the struggles and sacrifices made during the women’s rights movement. But I’m glad it was hopeful. This is a documentary about Gloria Steinem, her views and her experiences; not a documentary on the history of feminism.

Sheila Nevis, the president of HBO’s documentary film division, views

Gloria: In Her Own Words not as a biography but rather “

an inspirational film” for young people “

who didn’t know who she was.” For seasoned feminists who feel distraught over the plethora of incessant struggles, it’s nice to be buoyed by optimism. And for those who don’t call themselves feminists or don’t know much about the women’s movement, this might pique their curiosity to explore feminism. Inspiration is a powerful and sometimes underrated thing.

When someone leads a life in the spotlight, many myths and misconceptions may swirl around their public persona. But Steinem lays out her life: her triumphs, accomplishments, woes and heartbreak. It’s time you got to know the person you might think you knew, the woman who helped catalyze feminism in the U.S. I didn’t think it was possible to be even more inspired by Steinem than I already was…but I am.

,

,  , and the forthcoming

, and the forthcoming