Our February Theme Week for 2014 will be Women and Work/Labor Issues.

Women in the workplace has continued to be an incendiary topic in the U.S since WWII. Before that, Marxist thinker Frederich Engels formed the basis of Marxist Feminism when he wrote about gender oppression in 1884, insisting that class is the basis for the oppression of women. Wikipedia describes Engels theories from his book The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State:

Women’s subordination is a function of class oppression, maintained (like racism) because it serves the interests of capital and the ruling class; it divides men against women, privileges working class men relatively within the capitalist system in order to secure their support; and legitimates the capitalist class’s refusal to pay for the domestic labor assigned, unpaid, to women (childrearing, cleaning, etc.). Working class men are encouraged by a sexist capitalist media to exploit the dominant social position afforded to them by existing conditions to reinforce that position and to maintain the conditions underlying it.

We see this even now, 130 years later, with the limited opportunities that women have within the work force, the lack of value placed on the labor of women as evinced by the continuation of the unpaid child-rearing system, and the fact that women consistently earn less than men for performance of the same job (and that positions typically held by women tend to be compensated at a lesser wage).

On screen, we often see the demonization of women with professional power and/or ambition. These women are usually portrayed as callous, frigid (or conversely hyper-sexual), masculine, and even unnatural. These women tend to be fiercely competitive with other women in their field. All this tells viewers that women don’t belong in high-power positions.

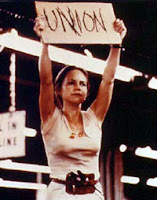

Conversely, there are a lot of stories about working class women who are filled with gumption and fortitude (if not a lot of education), which lionize the women who scrape to get by, keep their family fed, and struggle to improve their working conditions.

This month, we’d like to explore representations of women in the work force. Some questions you may want to think about are: How does being a woman affect the character(s)’ relationship with work? How does class intersect with gender oppression (or other kinds of oppression)? What does her job (skilled or unskilled labor) say about her? How does she relate to other women in her field? How does her job affect her interactions with men?

We’d like to avoid as much overlap as possible for this theme, so get your proposals in early if you know who or what you would like to write about. We accept both original pieces and cross-posts, and we respond to queries within a week.

Most of our pieces are between 1,000 and 2,000 words, and include links and images. Please send your piece as a Microsoft Word document to btchflcks[at]gmail[dot]com, including links to all images, and include a 2- to 3-sentence bio.

If you have written for us before, please indicate that in your proposal, and if not, send a writing sample if possible.

Please be familiar with our publication and look over recent and popular posts to get an idea of Bitch Flicks’ style and purpose. We encourage writers to use our search function to see if your topic has been written about before, and link when appropriate (hyperlinks to sources are welcome, as well).

The final due date for these submissions is Friday, Feb. 21 by midnight.

A sampling of films/shows that highlight women & work/labor issues:

Working Girl

Nine to Five

Commander in Chief

I Love Lucy

Laverne & Shirley

Murphy Brown

Who’s the Boss

Mr. Mom

Parenthood

Baby Boom

An Officer & a Gentleman

Waitress

The Passion/Crime d’amour (Love Crime)

The Devil Wears Prada

Judging Amy

The Good Girl

Ally McBeal