This guest post by Libby White appears as part of our theme week on Cult Films and B Movies.

I’ve loved Earth Girls Are Easy since I was a child. My mother and I would watch it together regularly, even though many of the sexual moments went beyond my comprehension at the time. Having become an adult in the 80s, my mother was a big fan of shows like In Living Color, and Star Trek: The Next Generation. And Earth Girls Are Easy can best be described as the love child of both.

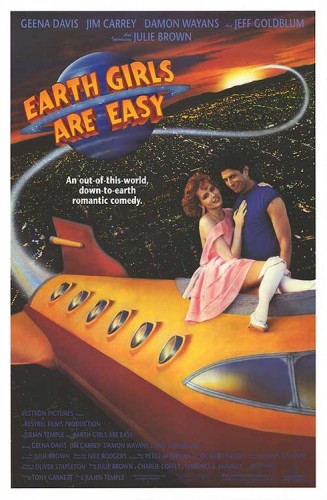

Campy, with over-the-top 80s style, and catchy, but ridiculous, musical numbers, it was a box office flop that faded into obscurity for many years. But it prevailed and has recently reemerged (thanks to DVD and the Internet), and has become a fledgling cult classic.

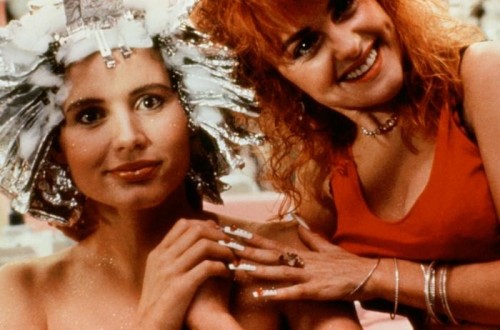

Taking place in San Fernando Valley, California, the movie revolves around Valerie Gail (Geena Davis), a love-sick manicurist who is desperate to please her unfaithful fiancé, Ted. A classic Valley-girl and hopelessly devoted, Valerie is shocked when a spaceship carrying three aliens suddenly lands in her pool one morning. When she realizes the three creatures are harmless, she takes them to her salon to be made over by her friend Candy (Julie Brown). Sheared of their colorful fur, the two women are delighted to realize that underneath, the aliens appear like normal, even attractive, human men. They decide to take the aliens out on the town, and end up at a crowded club, where Zeebo and Wiploc (Damon Wayans and Jim Carrey), become hits with the club’s women. Mac (Jeff Goldblum), has his eyes set on Valerie, however, and the two share a quiet moment together on the roof.

When Valerie finally takes the men back home, Ted is there waiting, and demands that the three men leave his house. Valerie reminds Ted that he no longer is welcome due to his cheating, and the police come and take him away. In an attempt to console her, Mac follows Valerie to her bedroom, and the two end up making love.

The next morning, Mac, Wiploc, and Zeebo repair the spaceship, and Mac announces that they will be ready to leave shortly. Valerie is visibly crestfallen, but is interrupted by an apologetic phone call from Ted. Unbeknownst to Valerie, Mac overhears her trying to work things out with Ted. Meanwhile outside, Woody, a pool-boy, comes by and convinces Wiploc and Zeebo to go to the beach with him to pick up women, and the three get caught up in an accidental robbery, a police chase, and a forced trip to the hospital. Valerie and Mac team up to break them out, using the aliens’ otherworldly powers to fool Ted, the attending doctor, and escape.

When they arrive back at home, Mac, believing Valerie to still be in love with Ted, uses his powers to distract her while he and his comrades move onto the now-working spaceship. Valerie snaps out of it however, and admits to Mac that she has fallen in love with him, and jumps onto the ship to join him. Candy happens by just as they take off into the sunset, and Valerie waves goodbye.

The casting for Earth Girls Are Easy is one of its best attributes, and it feels as if each character is essential to the movie. Each actor brought with him or her a special spark to the film from his or her own personal styles; Damon Wayans and Jim Carrey being the comedy, Jeff Goldblum the smoldering seduction, Julie Brown the music, and Geena Davis, the charisma.

Geena Davis is a long-time advocate for the fair representation of women in media, and has been a feminist icon for decades. And while Earth Girls was filmed several years before her rise into activism, Valerie Gail is a good female character (despite such stereotypical flaws as occasional air-headedness and thinking marriage will fix all of a relationship’s problems). She is the voice of reason to Candy’s party-girl recklessness with the aliens, and is as loyal as they come to those she cares about. And the chemistry between Geena Davis and Jeff Goldblum is palpable. Considering the two were married at the time of filming, it’s easy to believe that Valerie could meet and fall in love with Mac all within a day. Damon Wayans’ and Jim Carrey’s characters are adorably hilarious as well, stealing scene after scene with their constant troublemaking.

Julie Brown is truly at home as Candy, having both written and produced Earth Girls Are Easy based off of one of her original songs. She went on to make a stage show version of the film as well, clips of which can be found online. Several of Brown’s songs are included in the movie, either as major musical numbers or as background music. And while her “Valley Girl” characters are a defining part of her career, underneath the 80s slang, Brown is a triple-threat of talent. It is no question that without her, Earth Girls would have lost its fun spirit.

Being set in the Valley in the 80s, the film portrays much of the vapidness and consumerism popular at the time, with two of the film’s songs, “Brand New Girl,” and “’Cause I’m a Blonde,” focusing on changing or criticizing women’s appearances. “’Cause I’m a Blonde” is purposely satirical, however, and really serves more to make fun of the blonde “Valley Girl” stereotype than to support it. There is even a cameo from a long-forgotten social icon, Angelyne, which furthers the movie’s mocking of itself. Angelyne, while only briefly seen, was nominated for a Raspberry Award for her performance in Earth Girls, demonstrating the underlying level of petty hatred the public had for her and the lifestyle she represented. Still, Earth Girls itself almost tries to up-play the vapidness of its characters as a parody, as if trying to get the audience to laugh at the incredulousness of their behavior, while simultaneously rooting for them. More than 20 years later, I can only guess that the film originally provided a sense of escapism to the curious. A dose of supposed “Valley life” for those on the outside.

At times the movie can feel jarring; the most notable scene being when a conversation by the pool suddenly cuts to the musical number, “’Cause I’m a Blonde.” This was done to make up for several scenes that had been dropped from the final cut, and ends up leaving certain transitions into scenes overly noticeable.

Like every cult classic, Earth Girls Are Easy isn’t without its flaws. Luckily, its charm outweighs its imperfections. And while its high-energy goofiness may not be for everyone, it nevertheless has slowly been climbing the ranks of Cult Classics as it is rediscovered by old and new generations. If you ever need a shot of perky and fun energy, Earth Girls is the perfect film to deliver it.

Libby White is a self-proclaimed cinephile and Volunteer Firefighter who currently works as a Guard for Nissan’s headquarters in Tennessee.