|

| Cicely Tyson as Sipsey |

The radical notion that women like good movies

|

| Cicely Tyson as Sipsey |

This guest post by Mia Steinle previously appeared at Canonball and is cross-posted with permission.

In the late nineties, as I was entering early teenagerdom and as a group of marketers was inventing the term “tween,” my favorite movie was about a group of middle-aged divorcees waging war on their self-centered ex-husbands. The First Wives Club had come out in 1996, and it’s possible — nay, likely — that my parents rented it from our local Blockbuster shortly thereafter, but it wasn’t until some years later, at the dawn of a new millennium, that I was treated to this quintessentially 90s nugget of female empowerment, over and over again on my friend’s VCR.

|

| Diane Keaton, Goldie Hawn, and Bette Midler in The First Wives Club |

We admired Bette Midler as ballsy, street-smart Brenda, who is incensed that her ex-husband Morty has the gall to bring his girlfriend (Sarah Jessica Parker) to their son’s bar mitzvah. We laughed at Goldie Hawn as Elise, a habitually drunk, botoxed actress, whose producer ex-husband has just taken up with an even younger actress (Elizabeth Berkeley, whose performance makes SJP look like a comedic genius). And, while the other ladies are fun and glamorous, I think we were most touched by the neurotic realism of Diane Keaton as Annie, an anxious, eager-to-please, but ready-to-burst housewife whose husband (played by the Rev. Eric Camden, aka Stephen Collins) leaves her for their therapist.

After the suicide of a mutual friend — a woman who gave the best years of her life, and her self-esteem, to a man who then left her for a younger woman — the ladies band together to get back at their exes. As Annie explains, it’s a matter of justice; they made life easy for their ex-husbands for years, only to be discarded in middle-age — that time of life when society tries to force women into invisibility: sexually, romantically and professionally.

He wants to come home again and he feels emotionally ready to recommit to an equitable and caring relationship. I told him to drop dead.

|

| Film poster for The First Wives Club |

The First Wives Club is the story of four women who became friends with each other when they were in college. After graduation, the friends ended up drifting apart. This is a situation that happens to a lot of women. Life gets in the way.

People get married, have children, and (hopefully) find “real jobs.” It becomes increasingly difficult to find the time (or the energy) to socialize with friends who are no longer a part of our day-to-day lives. When you are in your 20s, you truly believe that you will be best friends forever. You intend to stay connected. Years later, you wonder whatever happened to those friends (whom you haven’t heard from in years).

In the movie, three of the friends reunite after learning that the fourth friend, Cynthia Swann Griffin (played by Stockard Channing) died by suicide after her husband divorced her. The surviving friends are now in their mid-forties. Each one is either divorced or is going through the process of divorce.

The movie does a good job of picking up on some of the thoughts that women who are 40 or over struggle with. Elise Elliot (played by Goldie Hawn) is overly concerned about aging. There is a scene where she begs her plastic surgeon to make her lips fuller (again). He resists, reminding her of all the plastic surgery she has already undergone and pointing out that she is beautiful.

|

| Elise looking for wrinkles at the plastic surgeon’s office |

She is a more extreme example of what many women (who are not actresses) feel when their hair starts turning gray and they begin to get “crow’s feet.” The fear is that these very natural parts of aging mean that the woman is no longer desirable, or sexy, or beautiful. There are women who are absolutely terrified of “getting old” because they worry that no one will want them.

Unfortunately, this fear is not an unfounded one. Elise’s husband, Bill Atchison (played by Victor Garber) is divorcing her and has started dating a woman who is much younger than than Elise. Tension builds when Elise is asked to play the role of “the mother” in a script where Bill’s new lover will play the lead role of the daughter.

A similar thing happened to Brenda Cushman (played by Bette Midler). She got married to Morton “Morty” Cushman when they were young, ran the cash register in his electronics stores, and had a son with him. Now, Brenda is 45 and Morty has left her and gotten into a serious relationship with Shelly Stewart (played by Sarah Jessica Parker). Brenda and Morty’s fifteen-year-old son has trouble coping with this situation.

Brenda laments to her friends that everything with she and Morty was just fine. Then, on their 20th wedding anniversary, Morty began having what Brenda calls a mid-life crisis. In short, he decides that she isn’t fun anymore and is holding him back. He replaces her with a thinner, younger, blond woman who is about half her age.

|

| “Who’s supposed to wear that? Some anorexic teenager?” |

Annie Paradis (played by Diane Keaton) has a slightly different story. She isn’t actually divorced yet. She and her husband Aaron Paradis (played by Stephen Collins) are separated. They had been going to couple’s therapy but now are each seeing a therapist individually. Annie truly believes that they are in the process of working things out and getting back together.

Her daughter, Chris Paradis (played by Jennifer Dundas) describes her mother as a “doormat.” Chris is a college student and old enough to see that her father isn’t treating her mother very well. She is frustrated that her mom allows it. Unlike Brenda’s son, Chris doesn’t want her parents to get back together.

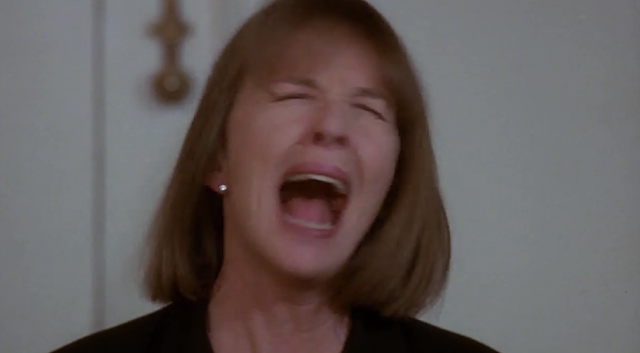

There is a scene where Annie is going on (what she believes) is a date with Aaron. She is convinced that he is going to tell her that he wants to get back together. Instead, after they have become intimate in his hotel room, he announces that he wants a divorce. This completely destroys Annie.

She is a woman who, like many women, has issues with self-esteem. After a lifetime of suppressing her anger, and striving to always be “nice,” Annie finally lets out her feelings in a loud, sobbing, messy way. At the same time, the phrase she uses most often during this catharsis is “I’m sorry.”

|

| Annie screaming “I’m sorry!!!” |

Later, the women start to want more than revenge. They decide to turn their efforts toward helping other divorced women. Again, this requires their ex-husbands, whom they have now managed to blackmail, to spend more money. To me, this part of the plot felt a bit forced and strange. The change from “let’s get ’em” to “let’s open a charity” was rather abrupt.

The First Wives Club was released in 1996, a time when almost no one carried a cell phone. As such, the majority of phone calls that take place in the movie are done on land-line phones with clunky receivers. There is a scene where Brenda goes out to dinner by herself. She doesn’t spend the meal fiddling with her cell phone – and neither do any of the other people in the restaurant. Times have changed since the late 1990’s (and realizing this makes me feel “old”).

|

| Poster for 3rd Rock from the Sun |

This is a guest post by Jenny Lapekas.

|

|

Upon their arrival, the aliens count their fingers and toes in their Rambler.

|

|

|

Although Mary is immediately drawn to Dick’s zany genius, she finds him an obnoxious office mate.

|

|

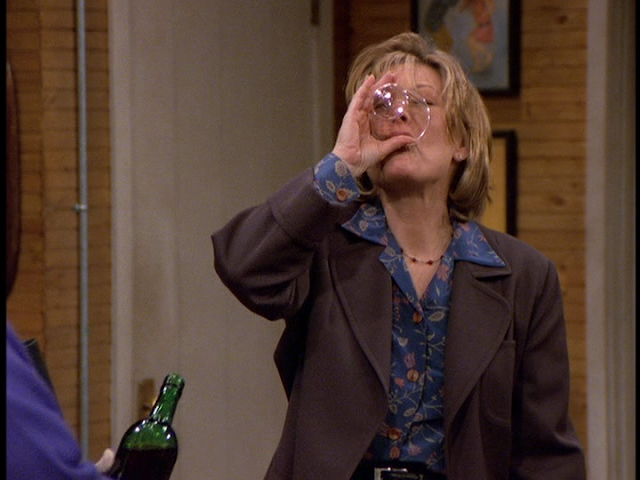

| Ironically, Mary’s love for wine renders her immune to the poison placed in her drink by alien-hunters. |

|

|

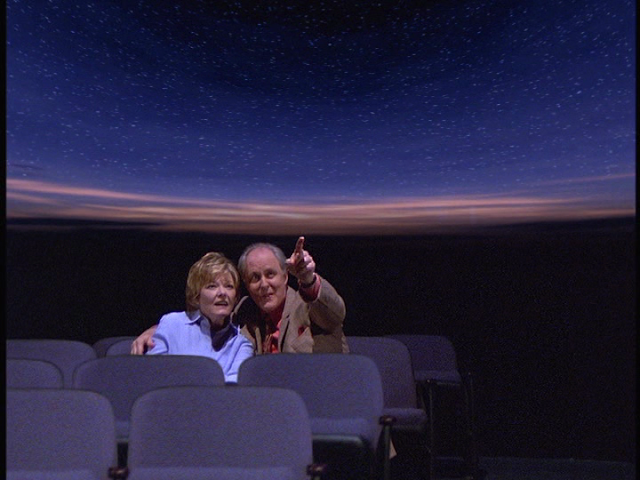

Mary is the only earthling who finds out that the Solomons are aliens, and Dick even points out their home planet for her.

|

|

|

Tommy and Dick stand off outside Mary’s front door. Tommy says, “For the first time on this planet, I’ve met a woman who appreciates me for what I think.”

|

|

|

When their mission is canceled, Dick tells Mary that she’ll remember him as “a feeling.”

|

|

| Movie poster for In a World … |

1) Number one and most important of all, I’m thankful this movie was written and directed by a woman and that it’s a story about a strong, smart, interesting woman.

|

| Director and screenwriter Lake Bell at the Sundance Film Festival |

I am incredibly thankful about that.

2) I’m thankful this movie stars an actress who doesn’t look like every other Hollywood actress. Yes, Bell is beautiful, but she also doesn’t have the button nose, full lips, perfect posture, and blond hair that has become so annoyingly ubiquitous among our female movie stars.

|

| Louis (Demetri Martin) and Carol Solomon (Lake Bell) sing their guts out in In a World … |

And neither do her co-stars…

|

| Louis (Demetri Martin) and Cher (Tig Notaro) watch Carol Solomon (Lake Bell) record a voice-over. |

(You also gotta love a movie that has both Tig Notaro and Geena Davis.)

3) On a related note, I’m thankful Bell’s protagonist, Carol Solomon, doesn’t always act like a leading lady—she shuffles, lurches, and acts generally spazzy. She doesn’t always look glamorous either—she doesn’t always wear makeup or look perfectly primped and often wears regular-people clothes (sweatpants, thermal underwear, t-shirts, football jerseys, overalls, ill-fitting dresses, etc.)—just like the rest of us.

|

| Louis (Demetri Martin) and Carol Solomon (Lake Bell) hatch plans to take over the voice-over industry. |

At the same time, I’m glad Carol looks attractive when she wants to without looking trashy or showing off all the goods.

4) I’m also thankful that several men are attracted to Carol even though she doesn’t know how to dress or stand up straight (and that the men who are drawn to her are attractive but not perfect either).

|

| Carol Solomon’s love interest, Louis (Demetri Martin) |

5) I love, too, that this film shows an intelligent, driven, attractive young female protagonist in a relationship, but it isn’t what defines her. Let me say that again: Thank God her relationship doesn’t define her!

I was equally thrilled that Carol had casual sex with some random guy she met at a party and celebrated it. And that she didn’t end up regretting her actions or have something bad happen to her as a result. In this movie, sex was just part of life—no big deal—much like it is in real life.

|

| Louis (Demetri Martin) and Carol Solomon (Lake Bell) karaoke the night away in In a World … |

6) I was also head over heels over the fact that the two sisters—Carol and Dani—were so close and leaned on each other for everything.

|

| Carol Solomon (Lake Bell) and her sister, Dani (Michaela Watkins) |

I was glad, as well, that the person who had an “affair” in this movie was a woman (rather than a man) and that she didn’t actually go all the way.

7) I really appreciate, too, that this movie shows a young person living at home with a parent and that she isn’t doing so because she’s a lazy, lost, unmotivated slacker.

|

| Carol Solomon (Lake Bell) and her father (Fred Melamed) argue about her career. |

And I was truly blown away by the film’s characterization of Carol’s family—a real family having down-to-earth, regular problems.

No, nobody is dying of cancer, nobody is mentally ill or disabled, nobody is in prison, nobody is an alcoholic. The characters in this movie are just average people with average problems—like jealousy, resentment, miscommunication, and selfishness.

I am very grateful about that.

|

| Carol Solomon (Lake Bell) and her father (Fred Melamed) on the way to an industry party. |

8) I’m thrilled about several things relating to Carol’s job…

I’m relieved Carol works in a non-glamorous industry that we don’t usually see featured in movies—the voice-over industry.

|

| Carol Solomon (Lake Bell) records a voice-over. |

I love, too, that she cares so much about her work even though it doesn’t pay the bills.

And I’m glad that the film shows her having some success in that field without totally dominating it a la every other movie ever made (Erin Brockovich, Jerry Maguire, The Devil Wears Prada, Working Girl, etc., etc.).

9) I’m downright ecstatic about the fact that Carol didn’t have to trip or fall to make us laugh, avoiding the ridiculous formulas that often dominate movies about women.

|

| Carol Solomon (Lake Bell) surrounded by her work notes in her bedroom at her father’s house. |

Thank you for that, Lake Bell!

Tangentially, it was also awesome that Carol was irritated by stupid people doing stupid things and didn’t apologize for that.

10) And last but not least, I’m incredibly thankful this movie made me laugh and feel and, for God’s sake, think.

|

| DVD cover for Elizabethtown |

|

| Kirsten Dunst (Claire) and Orlando Bloom (Drew) in Elizabethtown. This is just before Drew tells Claire she needn’t make jokes to be likeable. |

|

| “Do you ever just think, ‘I’m fooling everybody?'” — Claire |

|

| Sandra Bullock and Melissa McCarthy in ‘The Heat’ |

Written by Megan Kearns.

I was extremely excited to see The Heat. Sandra Bullock and Melissa McCarthy, both of whom I love, headlining a comedy? As a huge fan of Bridesmaids, seeing self-proclaimed feminist Paul Feig direct another lady-centric comedy got me giddy with excitement. AND with Bullock and McCarthy??? Yes, please! I don’t care what anyone says, Sandra Bullock is a fantastic actor, even in shitty films. And McCarthy is hilarious.

|

| No, no, no, just no |

And there’s Mullins’ five-minute (supposedly humorous) tirade on the size of her boss’ balls. How his balls are little “girl balls.” That’s right, let’s insult a guy by insulting the size of his testicles. Only “real” men have balls. Wait no, only “real” men have big balls. Newsflash, masculinity isn’t tied to scrotum size. And trans men may not have balls at all. They’re still men.

Then of course there’s DEA Agent Craig, aka The Albino. Did anyone else cringe at this?? God I hope so. Albinism is a disability. So now we’re making fun of people with disabilities for “looking like evil henchmen” and calling them “Snowcone??” Make it stop.

With all the offensive “jokes,” I was expecting fat-shaming jokes too. I loved that Melissa McCarthy’s weight was never an issue in the film. No jokes were made about her weight. Oh wait, I take that back. DEA Agent Craig tells her she looks “like the Campbell soup kid all grown up.” Really? We see Mullins as a sexually confident, assertive woman and we can’t get away without some fat-shaming snark? There is however an epic take-down of the horrors and toxicity of beauty culture in the form of Spanx. Yes, I’ve worn them, yes they are a demonic torture device. This was especially awesome considering the hideously disgusting fat-shaming vitriol Rex Reed spewed at McCarthy.

|

| Screw you, Spanx! |

But I have to say that while part of me is delighted to see different depictions of gender presentation, particularly non-stereotypical depictions of beauty (not every woman wants to wear dresses and lots of make-up), does Melissa McCarthy always have to be in slovenly clothes or ridiculous costumes in every movie I see her in?? She’s a beautiful woman. But it’s as if the films she’s in don’t believe that a plus-size woman can be. Why can’t we see a plus-size woman looking different? Or for that matter, why can’t we see more women of all sizes on-screen??

I did love Bullock and McCarthy’s camaraderie and watching their friendship unfold. And it’s fantastic to see two women over the age of 40 headlining a blockbuster movie. Especially when Hollywood abhors aging women and suffers from massive amounts of ageism. And you could tell they had a fucking blast making this movie. It was also awesome to not have a romance in the film, an aspect that delighted Feig as well. While there were flirtations, no romance upstaged the film. The ladies’ sisterhood took center stage.

While there’s very little commentary on gender and sexism, and an ass load of misogyny spewed by DEA Agent Craig — Sidebar, is that why it’s okay to make fun of his disability, because he’s a douchebag?? No, no, no — Ashburn and Mullins kind of “blow off misogynistic bullshit.” But thankfully there’s a very brief and subtle commentary on sexism in the workplace amidst a conversation between Ashburn and Mullins at a bar about how hard it is to be a woman in this line of work.

But did it have to follow in the shadow of buddy-cop movies by also containing transphobic, ableist and racist jokes? Couldn’t it have done without that??

Sadly I wasn’t a huge fan of The Heat. I wish I had been. But I just couldn’t get past the extremely problematic humor. Sigh. I wish it hadn’t been so racist, ableist or transphobic. I wanted to like this, especially because it was written by Katie Dippold, a writer and producer of my fave feminist TV show Parks and Rec. But feminism isn’t just about gender equality and putting more women in film. Although that’s a huge start. It’s about combating all forms of institutional discrimination and oppression. And not perpetuating prejudice.

|

| If only ‘The Heat’ could have been as awesome as these ladies. |

Despite its flaws, I wholeheartedly believe we need more female-centric films. Way more. And you know what? I’d rather have a female-centric movie I’m not a big fan of rather than none at all.

I’ve read that author (and very funny tweeter) Jennifer Weiner doesn’t like to criticize or speak negatively about books by other female writers because she knows how difficult it is for women to get published. And then when they do, male authors get reviewed more often, and typically by male critics, since gender disparity exists in the critic world too.

And I totally get why she does this. Sisterhood and solidarity can be extremely powerful. There’s a dearth of female film directors, female-fronted films, female screenwriters, female film critics. So I always feel guilty when I don’t lavish a female-centric/penned/directed film. But here’s the thing. I really shouldn’t have to worry about whether or not my critique is going to derail other female filmmakers. Not that I’m saying my words carry as much weight as say NY Times’ Manohla Dargis or anything. But I don’t want to add to the din of voices hyper-scrutinizing women-led films.

Then I can critique a film to my heart’s content without worrying that some asshat in Hollywood thinks they shouldn’t greenlight more women-centric films. Hollywood never thinks to stop making movies with male protagonists. One shitty dude-centric movie? Bring on more dude films. A shitty women-centric movie?? All lady movies must suck.

|

| Movie posters for Sixteen Candles |

Written by Stephanie Rogers (but not in time for Wedding Week).

Holy fuck this movie. I started watching it like OH YEAH MY CHILDHOOD MOLLY RINGWALD ADOLESCENCE IS SO HARD and after two scenes, I put that shit on pause like, WHEN DID SOMEONE WRITE ALL THESE RACIST HOMOPHOBIC SEXIST ABLEIST RAPEY PARTS THAT WEREN’T HERE BEFORE I WOULD’VE REMEMBERED THEM.

|

| “Chronologically, you’re 16 today. Physically? You’re still 15.” –Samantha Baker, looking in the mirror |

Ted: You know, I’m getting input here that I’m reading as relatively hostile.

Samantha: Go to hell.

Ted: Come on, what’s the problem here? I’m a boy, you’re a girl. Is there anything wrong with me trying to put together some kind of relationship between us?

[The bus stops.]

Ted: Look, I know you have to go. Just answer one question.

Samantha: Yes, you’re a total fag.

Ted: That’s not the question … Am I turning you on?

[Samantha rolls her eyes and exits the bus.]

|

| Samantha looks irritated when her stalker, Farmer Ted, refuses to leave her alone. Also Joan Cusack for no reason. |

Ted: You see, [girls] know guys are, like, in perpetual heat, right? They know this shit. And they enjoy pumping us up. It’s pure power politics, I’m telling you … You know how many times a week I go without lunch because some bitch borrows my lunch money? Any halfway decent girl can rob me blind because I’m too torqued up to say no.

Jake: I can get a piece of ass anytime I want. Shit, I got Caroline in my bedroom right now, passed out cold. I could violate her ten different ways if I wanted to.

Ted: What are you waiting for?

Jake: I’ll make a deal with you. Let me keep these [Samantha’s underwear, duh]. I’ll let you take Caroline home … She’s so blitzed she won’t know the difference.

|

| Ted carrying a drunk Caroline to the car |

And then Ted throws a passed-out Caroline over his shoulder and puts her in the passenger seat of a convertible. This scene took me immediately back to the horrific images of two men carrying around a drunk woman in Steubenville who they later raped—and were convicted of raping (thanks largely to social media). This scene, undoubtedly “funny” in the 80s and certainly still funny to people who like to claim this shit is harmless, helped lay the groundwork for Steubenville, and for Cleveland, and for Richmond, where as many as 20 witnesses watched men beat and gang rape a woman for over two hours without reporting it. On their high school campus. During their homecoming dance.

|

| Jake and Ted talk about how to fool Caroline |

People who claim to believe films and TV and pop culture moments like this are somehow disconnected from perpetuating rape need to take a step back and really think about the message this sends. I refuse to accept that a person could watch this scene from an iconic John Hughes film—where, after a party, a drunk woman is literally passed around by two men and photographed—and not see the connection between the Steubenville rape—where, after a party, a woman was literally passed around by two men and photographed.

|

| Caroline looks drunk and confused while Ted’s friends take a photo as proof that he hooked up with her |

Ted: Did we, uh …

Caroline: Yeah. I’m pretty sure.

Ted: Of course I enjoyed it … uh … did you?

Caroline: Hmmm. You know, I have this weird feeling I did … You were pretty crazy … you know what I like best? Waking up in your arms.

|

| The Heat movie poster. |

|

| Mullins (McCarthy) and Ashburn (Bullock) work together. |

|

| Ashburn and Mullins also drink together. |

|

| Mullins is shocked by the concept of Spanx. |

If women can laugh at men’s jokes–which doesn’t seem to be a problem–then men can laugh at women’s jokes. It’s pretty simple. The Heat shows us that. Cops, whiskey, drug rings, and a refrigerator full of guns and ammo may feel masculine, but Ashburn and Mullins show that women can wield it all.

The Heat made me laugh and cry.

I want more. I want theaters to be packed with genre films with women at the helm–in character, with the writing credits, as directors. The Heat 2 is already in the works, but there is so much opportunity for women in blockbusters. And I want dude-bros going to those movies in droves. I bet they will, too.

Now you need to believe it.

These female-led blockbusters are always “surprise,” hits, but how many times can you be surprised by the success of movies with female protagonists? At some point, you need to realize that people like this.

If you take up my plea and fund more female-centric films, I must warn you: some of them might not be awesome. Some may be mediocre, or bad. Just like movies with male leads. When Freddie Got Fingered bombed, the takeaway wasn’t that men can’t carry comedies. Remember that.

When the film ended, I stopped the trio of teenage boys and asked them if they liked the movie. It was unanimous: yes. I asked if they ever thought about not seeing it because the main characters were women. It was unanimous: no. (One exclaimed, “Not once.”)

Make them stop that.

|

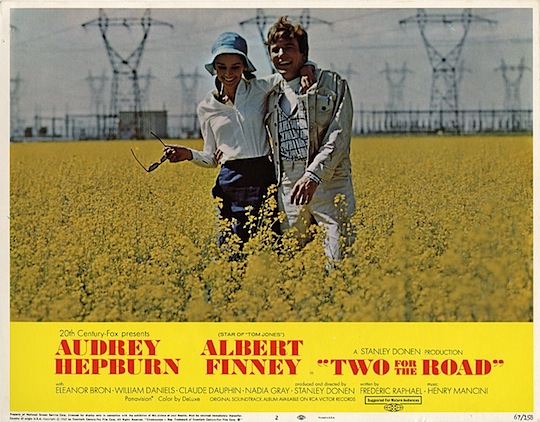

| Movie poster for Two for the Road |

Written by Myrna Waldron.

Written by Megan Kearns as part of our Infertility, Miscarriage and Infant Loss Week. Originally published at The Opinioness of the World. Cross-posted with permission.

“No, I was always adamantly against having a pole vaulting career, even though it’s what most women want…In Canada, it’s very big up there. You know, it’s meet a nice guy, get married, vault some poles. But I never wanted that.

Of course it’s one thing not to want something. It’s another to be told you can’t have it. I guess it’s just nice knowing that you could someday do it if you changed your mind. But now, all of a sudden that door is closed.”

“So I can’t have kids. Big deal. Now there’s no one to hold me back in life. No one to keep me from traveling where I want to travel. No one getting in the way of my career. If you want to know the truth of it, I’m glad you guys don’t exist. Really glad.”

|

| This is a local shop for local people. There’s nothing for you here. |

|

| Reece Shearsmith: yep and also yep. |

|

| Lots of shots like this, but heaven forfend we see her face. We might think she was an actual human being. |

Barbara: “They dug something up working on the new road.”Mrs. Levinson: “Oh, Barbara, stop it. You’re giving me the willies!”Barbara: “Well, you’re very welcome to mine – it’s coming off in a fortnight anyway.”

|

| But I sill love the show, and you should still watch it. |