Written by staff writer Lisa Bolekaja as part of our theme week on Black Families.

The first Black family sitcom (with under-aged children) I ever saw on TV was Good Times. For the majority of Black Americans raised in the 70s, The Evans Family was supposedly America’s first real exposure to a Black nuclear family on television, albeit one in extreme poverty living in the projects. I distinctly remember my mother and step-father sitting down with me to watch people who looked like us eating grits, turnip greens, or ribs on an old second –hand kitchen table the way we ate our own regular southern foods. Black families were such a rarity on television that Good Times became event viewing–the original must-see-TV in my neighborhood. The Evans family wasn’t as rich as The Brady Bunch, but they did go through comedic shenanigans that were solved at the end of the episode.

At the time I wasn’t aware of the problems actors James Amos and Esther Rolle dealt with trying to focus more attention on the family and not the stereotyped antics of J.J. (White producers and white writers wanted to up the ante on the clownish, uneducated, slapstick behavior of J.J, who eventually became the main focus of the show.) Good Times still had a nostalgic place in my heart. I used to own a Jimmy Walker J.J. Evans doll where you pulled the string in his back, and the toy would yell “Dyn-o-mite!” back at you. Even today, if TV Land or Centric plays re-runs, I will stop and watch it. On the heels of Good Times, came What’s Happening? and of course, the 80s brought the NBC savior/juggernaut, The Cosby Show, the 90s The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, and in the new millennium, The Bernie Mac Show, Everybody Hates Chris, and now Black-ish.

But I’m going to write something that may hurt some Black Americans’ feelings.

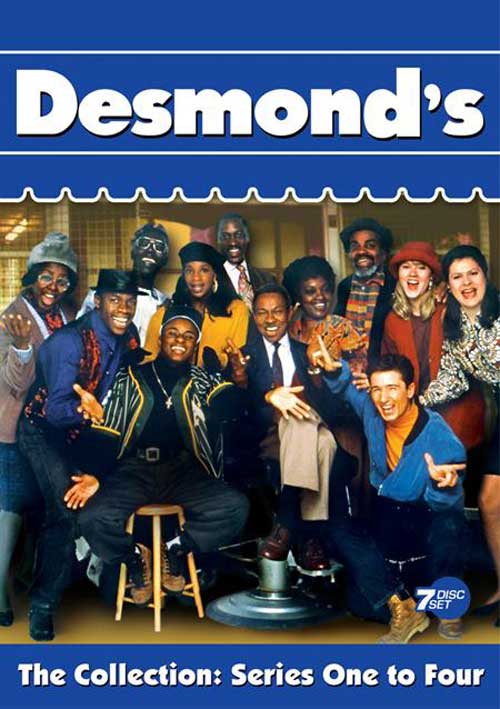

The best Black Family sitcom in my non-humble opinion is a little-known gem from across the pond that debuted in 1989. A show about a Black British/West Indian family running a barbershop in Peckham, London, it was called Desmond’s (created by Trix Worrell) and you need to buy it on DVD and watch it right now.

Desmond’s on the surface looks like any early 90s family comedy that served up plenty of corny jokes, familiar plots we’ve seen in similar family shows, and raucous studio audience laughter. What makes Desmond’s unique is its layered and often nuanced portrayal of immigrant Afro-Europeans and their assimilating progeny that are more closely connected to their African roots than any African American TV show I’d ever seen. It also has a cross representation of class in Black British society by showing retired, working class, upper-middle class, college-educated, college-bound, and not college-bound Black people interacting together all the time. Not only are different classes intermingling, but there are also four series regulars who are white, and their whiteness is not the punchline of tired racial jokes.

I was lucky to catch Desmond’s in the early 90s when Black Entertainment Television (BET) started airing re-runs in the states. I was cooking a box of mac ‘n cheese and flipping channels when I saw some Black actors I didn’t recognize. I had to turn the volume up to hear their voices because their patois sounded like the Jamaican folks I partied with at my local reggae dancehall. I watched every single episode BET aired.

Desmond Ambrose (Norman Beaton) was a popular calypso singer back in his native Guyana who immigrated to England with his beloved wife, Shirley Ambrose (Carmen Munroe). Desmond’s plan was always to work and live in England and then retire back to his native Guyana and build his dream home. Once settled in Peckham, Desmond and Shirley had three socially mobile children who were part of a wave of first generation Guyanese/Black Brits.

Shirley Ambrose has spent more than half her life in Peckham, and has no desire to return to Guyana. Her children are British, and she often fusses with Desmond about not sharing his dream of returning back home. Home is with her children in this new country. Their oldest son Michael (Geoff Francis) is a bank manager, a Buppie, and social climber. He fancies himself cultured, classy, and sometimes above his West Indian Roots. The middle child, Gloria (Kim Walker) is a college student, fashionista, and later in the series a professional writer who always calls Michael out on his pretentious behavior. Then there’s the youngest son Sean (Justin Pickett, my favorite), the first black teen geek and computer coder I’d ever seen on TV. What makes Sean special is that he is a computer whiz without being the cliché nerd, and he is a rapper and a D.J. He is smart, cool, and respectful of his parents and culture. Imagine Will Smith’s Fresh Prince combined with Carlton sans the corniness of both characters and you get an authentic Sean. So refreshing.

Desmond’s takes place inside a barbershop in a sometimes rough working-class neighborhood. The Ambrose family (without Michael) resides in an apartment above the shop, and three of their regular friends (and occasional customers) hang out there most of the day with them. One regular is Desmond’s Guyanese childhood friend and former band mate Porkpie (Ram John Holder). Another regular is Lee (Robbie Gee), a boxer and unofficial adopted son who often peddles goods inside and outside the shop. Still another drop-in is a West African from Gambia named Matthew (Gyearbuor Asante) who brings in his African culture and a grand sense of African pride. Matthew is also a university student who never seems to ever finish his studies, although he has been a student for many years. What I enjoy about Matthew is a new view of African characters. Often in Black American shows (especially the early TV shows in the 70s) African characters are made fun of, whether it is their names, food, or skin color. They are often depicted as being poor and overly grateful to be away from their homelands. Not Matthew. He has a superior air about him and comes from a wealthy family. He’s always chiding the West Indians that they need to respect their elder culture (Africa), while at the same time giving off the impression that he is delighted that West Indians have retained so many Africanisms in their own New World culture.

Desmond’s allowed me a peek into the world of my Black cultural cousins who wound up in England instead of the States. I learned West Indian history, I saw how Blacks over there also code-switched their language when they spoke among themselves and among outsiders. One minute the family would speak British Standard Vernacular English, and the next minute, flip into Guyanese patois, or even Black British Rude Boy Slang. This code-switching reminded me of my own people in the States where many of us speak Standard American English at work, African American Vernacular English (AAVE) at home or among friends, and can also slip into Southern Creole languages like Gullah (Geechee), or New Orleans Creole.

While Desmond’s was re-running in America, I was listening to a lot of British neo-soul music like Soul II Soul, Sade, Loose Ends, Tricky, Omar, The Young Disciples, and especially the songs of Caron Wheeler the singer whose voice put Soul II Soul’s sound on the map. Listening to Caron Wheeler’s album U.K. Blak, which was the title track, I was given a mini-history of how so many new West Indian immigrants landed in English ports. Caron Wheeler sang:

Many moons ago

We were told the streets were paved with gold

So our people came by air and sea

To earn a money they could keep

Then fly back home

Sadly this never came to be

When we learned we had just been invited

To clean up after the war

Back in ’49 never intended to stay here

Who could afford to leave these shoresUK Blak, ending the silence now

UK Blak, letting you know that we’re about

The opening credit sequence of Desmond’s shows actual black and white film footage of Blacks from the Caribbean on large British ships sailing into English ports after WWII. I watched Desmond’s, listened to Caron Wheeler sing some history to me, and felt an immediate connection to the characters on the show. I love Desmond’s more than most popular Black American shows I grew up with. It tells me more about my own history and roots from the viewpoint of my figurative cousins across the big water. Think about that for a minute. Every African American from enslaved America was merely one random port stop from being British, Brazilian, a Caribbean Islander, or a North American. Like Desmond’s people, African Americans migrated too, going North and West within America, leaving family back home in the deep south. Like Desmond’s people, we have strong roots in the south that some of us want to cut off and forget, and some of us have actually returned to retire there. A reverse migration. A returning to the old culture that sustained so many of us in the dark days from the Civil Rights struggles and back beyond that.

The younger siblings, Gloria and Sean, showed me that there was a cultural exchange of Black music and styles from the U.S. From the posters on their bedroom walls of Ice Cube, The Fresh Prince and Jazzy Jeff, Whitney Houston, and mentions of Michael and Janet Jackson, to the Malcolm X hats and T-Shirts that marked the debut of Spike Lee’s X. Rap music mixed into the ragamuffin sounds of Black England. The cultural cousins have been keeping in touch. As young Blacks in the States were calling out sexism and homophobia in rap culture, an episode of Desmond’s demonstrated that it was an issue in British rap too. Sean has to push back on his best friend Spider for selling rap/dancehall mash-up music that is sexist, misogynistic, and homophobic, making Sean’s openly gay university buddy Bernie feel uncomfortable around the school. Sean demands a safer space for his gay and female friends, even if it means cutting Spider out of his inner circle.

The show itself is available for purchase on DVD, but for only Seasons 1-4. A few years ago I was hunting for any copies of the series last two seasons. Luckily, I found Seasons 5 and 6 on YouTube. Desmond’s was a show that could’ve gone on for at least three more seasons. Unfortunately, the star of the show, Norman Beaton, died on a trip to visit his family in Guyana. There was an attempt to keep a part of the Desmond’s legacy alive with a spin-off series called Porkpie with Ram John Holder, but it was short-lived, lasting only two seasons.

Just to entice any potential new fans, you will spot some familiar faces in some of the episodes. The very cute white barber/ stylist Tony was played by Dominic Keating who later went on to star on the TV series Star Trek: Enterprise.

A brother-in-law of Gambian forever-student Matthew was played by Joseph Marcell, who later gained American fame playing Geoffrey the butler on The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.

And for some real fun, if you watch an early episode called Veronica, you will see the child actress Amma Assante who grew up to direct the phenomenal movie Belle from last year.

Do yourself a favor. Come ‘round the shop and listen to some Soca. There will be tea and toast and good times. I promise.