This is a guest review by Myrna Waldron.

|

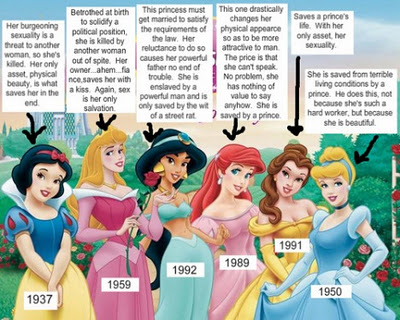

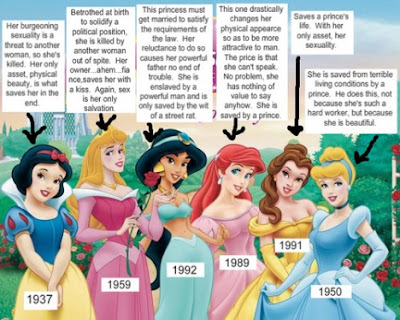

| “The sarcasm is practically melting off the screen!” |

But first, a few caveats. For the sake of my sanity, I will only be examining the original films that the characters first appeared in. No sequels, no supplemental film merchandising, no consideration of the Disney Princess merchandising line. Second, there is a lot of truth in the feminist criticisms targeted at the Disney Princesses. I credit most of these truths, however, to the contextual historical origins of the stories. The Grimm Brothers, Charles Perrault and Hans Christian Anderson predate modern feminism, as do the films made before the 1960s. Lastly, I will be concentrating on the 6 most common targets: Snow White, Cinderella, Aurora, Ariel, Belle and Jasmine. With all that clarified, let’s begin.

|

| “I wish I could get animals to help me do my chores.” |

Her song, “I’m Wishing”, reflects her emotional depth of character. It is not specifically a handsome boyfriend she longs for, she is longing for someone to love. That’s quite understandable considering she has lost everyone who loved her. “I’m Wishing” is a prayer for affection; “I’m hoping and I’m dreaming of the nice things he’ll say.” Her subsequent infatuation with the prince who meets her is another aspect of her personality. Since she is barely out of childhood, she still has a childlike trust and strong affection for anyone who treats her with kindness; we see this again later in her relationship with the Dwarfs, and her unfortunate trust in the disguised Queen.

What, then, of her famous domestic talents? Note that once she’s left the castle, she doesn’t do chores because she is expected to or forced to do them. When she stumbles upon the dwarfs’ cottage, she wonders if the messiness is because the inhabitants are orphaned children like herself. She sees herself in this situation; a motherless child forced to fend for herself. Her inherent sweetness and kindness shines through here. She volunteers to clean up the cottage because she does not want to deny anyone else that which she has been denied. This, I think, is a good feminist message. Women have been, and are, often denied rights and marginalized, but it is our conviction that someday this will end, and that if we can prevent it, or do anything else to help someone in a similar situation, we will gladly do so. And, like Snow White, when confronted with a difficult job, we will “Whistle While You Work” to give us strength to get through it.

|

| “So pure-hearted she can touch bubbles without bursting them.” |

I take further issue with the dismissal of Cinderella’s character as weak. Right at the start of the film, she displays a strong will, and a sharp wit. Her sarcastic ranting at the castle’s bells remains my favourite scene in the movie. She also has a strong rebellious streak; I highly doubt her stepfamily would have approved of her releasing the mice from the traps and her giving them little hats and shirts. This strong will and sense of rebellion comes to a point when Cinderella hears that every eligible maiden is to attend a ball held for the returning Prince. Her assertion that she is able to attend the ball as well is an assertion of her rights as a woman. Despite her marginalization and abuse from her family, she is, in this invitation, considered an equal. When her stepfamily tries to ensure she will not have time to make a dress, Cinderella steels herself not to be too disappointed about missing out on the ball, showing further strength of character. It is only when her stepsisters destroy her dress (in a scene disturbingly reminiscent of sexual assault) that she finally falls into despair; it is one abuse too many. I cannot fault her for her reaction at this point, as not only has she endured horrific emotional and physical abuse, she has yet again been denied one of the few things she has asked for. The ball, for Cinderella, represents her marginalized rights. At the ball, there is no class distinction, she has a chance to have fun for once, and she has a chance to meet other people (not just the prince). Her stepfamily can thus be interpreted as a representation of people who deny rights to women, and Cinderella can thus stand in for the oppressed women who fight against misogyny.

|

| “Aurora’s side of the wedding chapel was entirely comprised of animals.” |

Aurora has thus grown up only displaying the traits that the fairies’ magicked into her, and they have never allowed her to develop into anything other than their ideal. The fairies idealized Aurora so much that they never think to consider that she has a mind and a will of her own, and assume she would be overjoyed that they kept vital secrets from her for her entire life. In many ways, though it was with the best of intentions, the fairies/aunts have done Aurora a great disservice. Their loyalty and promise to the king seems to supersede their loyalty to someone they have raised like a daughter. Though Maleficent must magically hypnotize Aurora into touching the spindle, I believe it is the fairies’ insistence on obedience above all that partly led to Aurora’s downfall. In Aurora’s case, my feminist defense of her character will be one of empathy for her.

|

| “Disney’s ode to teenage angst.” |

Lastly, I wish to shortly refute the criticisms about the climax of the film. It is true that Ariel was incapacitated by Ursula’s magic, and that it was Eric who ultimately killed Ursula. However, only moments earlier, Ariel physically fought against Ursula, and even forced Ursula into accidentally destroying her pet eels, so she is obviously not weak and submissive here. I also think of the incapacitation as a dark echo of a sentiment Ariel expressed earlier in the “Part of Your World Song”; “Sick of swimming, ready to stand.” As a mermaid, she feels and has been exploited into uselessness, as a human, she’s ready not only to physically stand, but to metaphorically stand up for herself.

|

| “I sing to my books all the time, don’t you?” |

Feminist messages in the film are also easily indicated by the differences between Belle’s two suitors, the Beast and Gaston. At first, there is not much difference between the men; neither initially takes Belle’s wishes and desires into account when courting her. Note that Belle is undaunted by the lack of respect shown by the men; she ignores Gaston’s dismissal of her interests and responds to his flirtations with sarcasm, and she stands up to the Beast when he has his temper tantrums. Interestingly, both actions demonstrate different kinds of courage: to rebuff the advances and “advice” of a leader of the village shows further confidence and courage in her nonconformity, and to stand up to and argue with a physical embodiment of fear is symbolically feminist of our efforts to stand up to those that would use fear to subdue us.

Later on, Gaston openly proposes to Belle, and affirms his characterization as a male chauvinist. His plans for his marriage to Belle involve forcing her into subservience; he fantasizes about her massaging his feet and bearing him 6 or 7 “strapping” boys (he evidently doesn’t value female children). Once again, he shows no concern for Belle’s wishes and assumes that this life is what all women dream of. Once Beast’s personality starts to change, he differentiates himself from Gaston. He no longer tries to force her affections (such as the demand that she join him for dinner), and shows that he values her intellectualism and cares about her interests when he gifts her the library. In the third act, there is almost a role reversal in the evolution of Gaston and Beast’s characters. Gaston tries to “trap” Belle into marriage through blackmail, and the Beast officially “frees” Belle (though at this point she is arguably staying in the castle willingly) out of love for her, knowing that she may never return. The suitors’ very different approaches to relationships thus serve as excellent examples for the types of relationships that feminists seek to end/embrace: We reject relationships solely based on the wants and desires of the man with no consideration of the woman’s feelings, and seek relationships of mutual respect and understanding, with careful consideration of the interests, wants and desires of both partners.

|

| “I like making you feel uncomfortable.” |

Jasmine is characterized as a woman with an intelligence, courage and wit that surprises the men around her (which is perhaps a subtle jab at Middle Eastern oppression of women). Her escape from the palace shows a feminist emotional fortitude; she will put her happiness first. She catches on to Aladdin’s schemes very quickly, showing that she is just as clever about getting out of bad situations as he is. One particularly controversial scene (the one I have pictured) involves her quick-thinking abilities. In order to distract Jafar, she exploits his attraction to her by pretending that she has magically fallen in love with him. It is partly a scene about using her sexuality as a weapon, but I also believe that her actions are equally as much about utilizing her intelligence and adaptability to any situation.

|

| “How can you tell this is fanart? The Characters show an actual personality.” |

—–