This repost by Amanda Rodriguez appears as part of our theme week on Unlikable Women.

As a follow-up to my post on the Top 10 Superheroines Who Deserve Their Own Movies, I thought it important to not neglect the bad girls of the superhero universe. I mean, we don’t want to piss those ladies off and invoke their wrath, do we? While villainesses often work at cross-purposes with our heroes and heroines, we love to hate these women. They’re always morally complicated with dark pasts and often powerful and assertive women with an indomitable streak of independence. With the recent growing success of Disney’s retelling of their classic Sleeping Beauty, the film Maleficent shows us that we all (especially young women) are hungry for tales from the other side of the coin. We want to understand these complex women, and we want them to have the agency to cast off the mantle of “villainess” and to tell their own stories from their own perspectives.

1. Mystique

Throughout the X-Men film franchise, the blue-skinned, golden-eyed shapeshifting mutant, Mystique, has gained incredible popularity. Despite the fact that she tends to be naked in many of her film appearances, Mystique is a feared and respected opponent. She is dogged in the pursuit of her goals, intelligent and knows how to expertly use her body, whether taking on the personae of important political figures, displaying her excellent markmanship with firearms or kicking ass with her own unique brand of martial arts. As the mother of Nightcrawler and the adoptive mother of Rogue, Mystique has deep connections across enemy lines. X-Men: First Class even explores the stigma surrounding her true appearance and the isolation and shame that shapes her as she matures into adulthood. The groundwork has already been laid to further develop this fascinating woman.

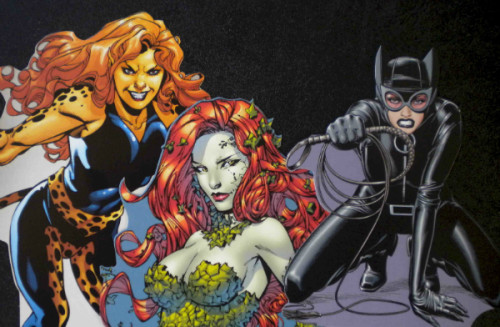

2. Harley Quinn

Often overshadowing her sometime “boss” and boyfriend The Joker, Harley Quinn captured the attention of viewers in the Batman: Animated Series, so much so that she was integrated into the DC Batman comic canon and even had her own title for a while. She’s also notable for her fast friendship with other infamous super villainesses, Poison Ivy and Catwoman. Often capricious and unstable, Harley always looks out for herself and always makes her own decisions, regardless of how illogical they may seem. Most interestingly, she possesses a stark vulnerability that we rarely see in villains. A dark and playful character with strong ties to other women would be a welcome addition to the big screen.

3. Ursa

Ursa appears in the film Superman II wherein she is a fellow Krypontian who’s escaped from the perpetual prison of the Phantom Zone with two other comrades. As a Kryptonian, she has all the same powers and weaknesses of Superman (superhuman strength, flight, x-ray vision, freezing breath, invulnerability and an aversion to kryptonite). Ursa revels in these powers and delights in using extreme force. Ursa’s history and storyline are a bit convoluted, some versions depicting her as a misunderstood revolutionary fighting to save Krypton from its inevitable destruction, while others link her origins to the man-hating, murderous comic character Faora. Combining the two plotlines would give a movie about her a rich backstory and a fascinating descent into darkness in the tradition of Chronicle.

4. Sniper Wolf

Sniper Wolf from Metal Gear Solid is one of the most infamous and beloved villainesses in gaming history. A deadly and dedicated sniper assassin, Sniper Wolf is ruthless, methodical and patient when she stalks her prey, namely Solid Snake, the video game’s hero. Not only that, but she has a deep connection to a pack of huskies/wolves that she rescues, which aid her on the snowy battlefield when she faces off with Snake in what was ranked one of gaming’s best boss fights. In fact, Sniper Wolf has made the cut onto a lot of “best of” lists, and her death has been called “one of gaming’s most poignant scenes.” Her exquisite craft with a rifle is only one of the reasons that she’s so admired. Her childhood history as an Iraqi Kurdish survivor of a chemical attack that killed her family and thousands of others only to be brainwashed by the Iraqi and then U.S. governments is nothing short of tragic. Many players regretted having to kill her in order to advance in the game. She is a lost woman with the potential for greatness who was manipulated and corrupted by self-serving military forces. Sniper Wolf is a complex woman of color whose screenplay could detail an important piece of history with the persecution of Kurds in Iraq, show super cool weapons and stealth skills while critiquing the military industrial complex and give a woman a voice and power within both the male-dominated arenas of spy movies and the military.

5. Scarlet Witch

Scarlet Witch, the twin sister of Quicksilver and daughter of Magneto, is one of the most powerful mutants in the X-Men and Avengers universe. With power over probability and an ability to cast spells, Scarlet Witch is alternately a valuable member of Magneto’s Brotherhood of Mutants as well as the Avengers. She can also manipulate chaos magic and, at times, control the very fabric of reality, such that she can “rewrite her entire universe.” Um, badass. She’s also one of the most interesting characters in the X-Men and Avengers canon because she’s so deeply conflicted about what she believes and who she should trust. Eventually coming around to fight on the side of good, Scarlet Witch has a true heroine’s journey, in which she has a dark destiny that she overcomes, makes choices for which she must later seek redemption, finds her true path as a leader among other warriors, and she even becomes a mother and wife in the process. Despite her extensive comic book history (first appearing in 1964) and the fact that she’s such a strong mutant with such a compelling tale of the journey from dark to light, Scarlet Witch has only been a supporting character in video games, TV shows, and in movies (most recently set to appear in the upcoming Avengers: Age of Ultron). That’s just plain dumb.

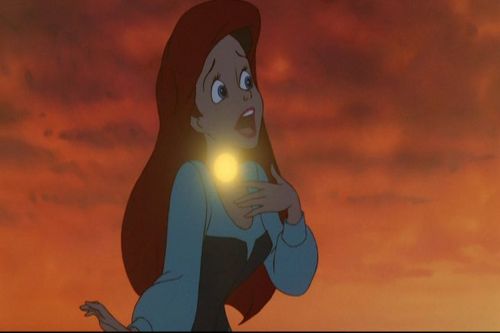

6. Ursula

Ursula, the sea witch from Disney’s The Little Mermaid, is so amazing. Part woman, part octopus, she has incredible magical powers that she uses for her own amusement and gains. With her sultry, husky voice and sensuous curves, she was a Disney villainess unlike any Disney had shown us before. What I find most compelling about Ursula is that her magic can change the shape and form of anyone, and she chooses to maintain her full-figured form. Though she is a villainess, this fat positive message of a magnetic, formidable woman who loves her body (and seriously rocks the musical number “Poor Unfortunate Souls” like nobody’s business) is unique to Disney and unique to general representations of women in Hollywood.

[youtube_sc url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xLSnNSqs_CQ”]

Now that Disney has made Maleficent, they better find a place for this octo-woman sea witch, and they better keep her gloriously fat, or they’ll be sorry.

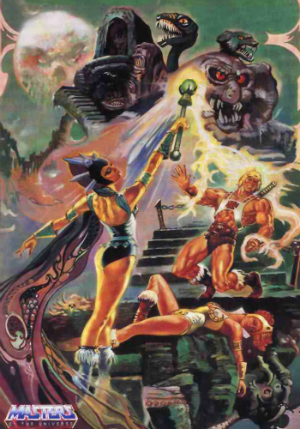

7. Evil-Lyn

Evil-Lyn was the only regularly appearing villainess on the 80’s cartoon series He-Man and the Masters of the Universe. Unlike its blissfully female-centric spin-off, She-Ra: Princess of Power, He-Man was pretty much a sausage-fest. Much in the way that Teela and the Sorceress were the only women representing the forces of good, Evil-Lyn was the lone lady working for the evil Skeletor. As his second-in-command, she proved herself to be devious and intelligent with a gift for dark sorcery that often rivaled that of the seemingly much more powerful Skeletor and Sorceress. There appears to be no official documentation of this, but as a child, I read Evil-Lyn as Asian (probably because of her facial features and the over-the-top yellow skin tone Filmation gave her). I love the idea of Evil-Lyn being a lone woman of color among a gang of ne’er-do-wells who holds her own while always plotting to overthrow her leader and take power for herself. (Plus, she has the best evil laugh ever.) I have no illusions that she’ll ever get her own movie (despite Meg Foster’s mega-sexy supporting performance as the cunning Evil-Lyn in the Masters of the Universe film). However, I always wanted her to have more screen time, and I always wanted to know more about her, unlike her male evil minion counterparts.

8. Knockout and Scandal

Scandal Savage and Knockout are villainess lovers who appear together in both comic series Birds of Prey and Secret Six. As members of the super-villain group Secret Six, the two fight side-by-side only looking out for each other and, sometimes, their teammates. Very tough and nearly invulnerable due to the blood from her immortal father, Vandal Savage, Scandal is an intelligent woman of color who’s deadly with her Wolverine-like “lamentation blades”. Her lover Knockout is a statuesque ex-Female Fury with superhuman strength and a knack for not dying and, if that fails, being resurrected. I love that Scandal and Knockout are queer villainesses who are loyal to each other and even further push the heteronormative boundaries by embarking on a polygamous marriage with a third woman. I generally despise romance movies, but I would absolutely go see an action romance with Scandal and Knockout as the leads!

9. Lady Death

Lady Death has evolved over the years. Beginning her journey as a one-dimensional evil goddess intent on destroying the world, her history then shifted so that she was an accidental and reluctant servant of Hell who eventually overthrows Lucifer and herself becomes the mistress of Hell. Her latest incarnation shows her as a reluctant servant of The Labyrinth (instead of the darker notion of Hell) with powerfully innate magic that grows as she adventures, rescuing people and saving the world, until she’s a bonafide heroine. An iconic figure with her pale (mostly bare) skin and white hair, Lady Death has had her own animated movie, but I’m imagining instead a goth, Conan-esque live action film starring Lady Death that focuses on her quest through the dark depths of greed, corruption and revenge until she finds peace and redemption.

10. Asajj Ventress

Last, but not least, we have Asajj Ventress from the Star Wars universe, and the thought of her getting her own feature film honestly excites me more than any of the others. I first saw Ventress in Genndy Tartakovsky’s 2003 TV series Star Wars: Clone Wars, and she was was mag-fucking-nificent. A Dark Jedi striving for Sith status, Ventress is a graceful death-dealer wielding double lightsabers. Supplemental materials like comic books, novels and the newer TV series provide more history for this bald, formidable villainess. It turns out that she’s of the same race as Darth Maul with natural inclinations towards the Force. Enslaved at a young age, she escaped with the help of a Jedi Knight and began her training with him. She was a powerful force for good in the world until he was murdered, and in her bitterness, she turned to the Dark Side. Her powers are significant in that she can cloak herself in the Force like a mist and animate an army of the dead (wowzas!). Confession: I even have a Ventress action figure. The world doesn’t need another shitty Star Wars movie with a poorly executed Anakin Skywalker; the world needs a movie about Asajj Ventress in all her elegantly brutal glory.

Peeling back the layers of these reviled women of pop culture is an important step in relaxing the binary that our culture forces women into. Showing a more nuanced and empathetic version of these women would prove that all women don’t have to be good or evil, dark or light, right or wrong, virgin or whore. Why do we love villainesses? Because heroines can be so bloody boring with their clear moral compasses, their righteousness and the fact that they always win. When compared to their heroine counterparts, villainesses have more freedom to defy. In fact, villainesses are more likely to defy expectations and gender roles, to be queer and to be women of color. In some ways, villainesses are more like us than heroines because they’re fallible, they’ve suffered injustices and they’re often selfish. In other ways, villainesses are something of an inspiration to women because they’re strong, confident, intelligent, dismissive of the judgements of others and, most importantly, they know how to get what they want and need.

Recommended Reading:

Top 10 Superheroines Who Deserve Their Own Movies

Top 10 Superheroes Who Are Better As Superheroines

Top 10 Superheroine Movies That Need a Reboot

The Many Faces of Catwoman

Dude Bros and X-Men: Days of Future Past

She-Ra: Kinda, Sorta Accidentally Feministy

Women in Science Fiction Week: Princess Leia: Feminist Icon or Sexist Trope?

The Very Few Women of Star Wars: Queen Amidala and Princess Leia

Wonder Women and Why We Need Superheroines

Monsters and Morality in Maleficent

Bitch Flicks writer and editor Amanda Rodriguez is an environmental activist living in Asheville, North Carolina. She holds a BA from Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio and an MFA in fiction writing from Queens University in Charlotte, NC. She writes all about food and drinking games on her blog Booze and Baking. Fun fact: while living in Kyoto, Japan, her house was attacked by monkeys.