The Violent Vagina: The Real Horror Behind the Teeth by Belle Artiquez

It’s a conundrum, one that Dawn faces head (or vagina) on. She is forced to confront these opposing views, and her body reacts the only way it knows how, it bites the penis of society, it castrates the men that want to turn her into something she doesn’t want to be: a sexual young woman.

Salt: A Refreshing Genderless Lens by Cameron Airen

Violent films with a female at their center tend to be viewed differently than violent films with a male lead. When a woman is in this role, it’s controversial. When a man is in the same type of role, it’s a part of who he is as a human being. We’ve become numb to the violence that men engage in onscreen. As a result, we don’t criticize it like we do when a woman is engaging in it.

Shieldmaidens: The Power and Pleasure of Women’s Violence on Vikings by Lisa Bolekaja

In Reel Knockouts: Violent Women in the Movies, Neal King and Martha McCaughey assert that “cultural standards still equate womanhood with kindness and nonviolence, manhood with strength and aggression.” Under the Victorian cult of true womanhood, womanly virtue was supposed to encompass piety, purity, submissiveness, and domesticity. Thank goodness writer/producer Michael Hirst ignored those virtues by creating two dynamic women warriors with his historical drama Vikings.

Emotional Violence, Kink, and The Duke of Burgundy by Rushaa Louise Hamid

In much of feminist literature from the past, kink is seen an act driven by patriarchy, with submissive women reproducing their oppressions in the bedroom and capitulating to gendered norms of women as silent and subservient. Even nowadays as the tide gradually changes, there is still a large amount of ire reserved for those who practice BDSM.

Violence and Morality in The 100 by Esther Nassaris

This act of mercy killing is the first of many moments when Clarke is forced to be violent for the good of others. It not only prompts an important change within herself – she loses her idealistic ways – but it prompts a change in the group dynamics. After this moment, Clarke begins to pull away from the co-leadership she and Bellamy had operated in and moves toward becoming the sole leader of the delinquents.

The Rising “Tough” Women in AMC’s The Walking Dead Season Five by Brooke Bennett

This season seems to present a large change in representational issues by including complex characters of color that we actually know something about and care for, presenting the couple of Aaron and Eric from the Alexandria community and self-pronounced lesbian Tara, and doing away with the innate equation of vagina equals do the laundry while the men go kill all the zombies.

Nine Pretty Great Lesbian Vampire Movies by Sara Century

Almost unfailingly exploitative in its portrayal of queer women, this specific sub-genre of film stands alone in a few ways, not the least of which being that the vampires, while murderous and ultimately doomed, are powerful, lonely women, often living their lives outside of society’s rules.

The Real Mother Russia: Modernising Murder and Betrayal in The Americans by Dan Jordan

The ideological battle between the FBI and KGB is thus a gendered one, as the national characters of Uncle Sam and Mother Russia are pitted against each other on a more even world stage.

Monster: A Telling of the Real Life Consequences for Violent Women by Danika Kimball

Throughout her life, Wuornos experienced horrific instances of gendered abuse, which eventually lead to a violent outlash at her unfair circumstances. Monster vividly documents the life of a woman whose experiences under a dominant patriarchal culture racked with abuse, poverty, and desperation led to a life of crime, imprisonment, and eventually death.

Stoker–Family Secrets, Frozen Bodies, and Female Orgasms by Julie Mills

Her uncle’s imposing presence has awakened in her at the same time a lust for bloodshed and an intense sexual desire, and she promptly begins to experiment and seek out means with which to satisfy both.

Sons of Anarchy: Female Violence, Feminist Care by Leigh Kolb

At the end of season 6, Gemma violently clashes the spheres of power. She’s in the kitchen. She’s using an iron, and a carving fork. Using tools of the feminine sphere, she brutally murders Tara, because she fears that Tara is about to take control and dismantle the club—the life, the style of mothering and living—that she brought home with her so many years ago.

What’s in a Name: Anxiety About Violent Women in Monster, Teeth, and The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo by Colleen Clemens

The first college course I ever developed focuses on women and violence. Stemming from my interest in women who enact violence on and off the page, I wanted to ask students to think about our perceptions of women as “naturally” peaceful.

Hard Candy: The Razor Blade Hidden in an Apple-Cheeked Confection by Emma Kat Richardson

Hogtying and drugging Jeff is only the tip of Hayley’s sadistic iceberg: over the course of the next several hours, she subjects him to a series of tortures more at home in Guantanamo Bay than a sleepy suburban neighborhood, including spraying his screaming mouth with chemicals, temporarily suffocating him with cellophane, and attacking him with a taser in the shower.

High Tension: Rethinking Female Sexuality and Subjectivity Through Violence by Laura Minor

Rather than pander to the male gaze, Aja decides to reject these scopophilic pleasures in favour of championing female subjectivity, but he also chooses to reject heteronormativity by having the lesbian desires of Marie drive the plot of the film. Interestingly, it is these desires and subjective experiences that both initiate the use of violence and intensify the representation of violence throughout.

“It is not fitting for her to be so manly and terrifying”: Catharsis and Female Chaos in Pasolini’s Medea by Brigit McCone

Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1969 film Medea was created in the aftermath of Italian fascism, another masculine cult of personal self-sacrifice in the interests of the state. Utilizing the operatic charisma of the legendary Maria Callas in a non-singing role, he harnesses the pitiless woman as an agent of chaos, rebelling against the dictates of the masculine state that urges her husband to discard her, in favor of a politically advantageous match.

Domestic Terrorism: Feminized Violence in Misery by Tessa Racked

Annie is a human being, dangerous not because of an evil supernatural force, but rather a severe and untreated mental illness. Although Annie is not given an official diagnosis in the film or the novel, an interview with a forensic psychologist on the special edition DVD characterizes her as displaying symptoms of several different conditions, including borderline personality disorder (BPD).

Girlhood: Observed But Not Seen by Ren Jender

Girlhood starts on a peak note: a slow-motion scene of what looks like Black men playing American tackle football on a field at night, wearing helmets, shoulder pads and mouth guards, so we don’t realize–until we notice the players’ breasts under their uniforms–that they are all girls.

Patty Jenkins’ Monster: Shouldering the Double Burden of Masculinity and Femininity by Katherine Parker-Hay

In this narrative we see masculinity float free from any ties to the male body, femininity float free from any easy connection to frailness – we see them meet in the one body of this working class woman to excruciating effect.

Feminist Fangs: The Activist Symbolism of Violent Vampire Women by Melissa-Kelly Franklin

The acts of violence by the female protagonists are terrifying, swift, and socially subversive. They target misogynistic representatives of the patriarchal society that oppresses and silences women, taking them out one by one.

Slashing Gender Assumptions: The Female Killer, Unmasked by Kate Blair

To a certain extent, the reveal of woman as killer in both films comes across as a “gotcha” moment. After an hour or so of being scared out of your wits, it’s both surprising and puzzling to see a woman emerge as the killer. In the real world, most documented violent crimes are committed by men, but in a film, where anything can happen, there’s no reason to make this assumption.

“Did I Step on Your Moment?” The Seductive and Psychological Violence of Female Superheroes by Mary Iannone

This style of fighting codes our female superheroes as half menacing and half attractive – we are meant to be afraid of them, but also enticed by them. Their violence is inextricably linked to their sexuality.

Nobody Puts Susan Cooper in the Basement: Melissa McCarthy and Skillful, Competent Violence in Film by Laura Power

As McCarthy tousles with her own nemesis in the kitchen fight, Feig uses slow motion to let us savor the violence and bird’s eye shots to let us see the controlled swings of Cooper’s arms and legs as she fights. The violence is not slapstick. The violence is not played for laughs. The violence is just flat-out cinematically terrific.

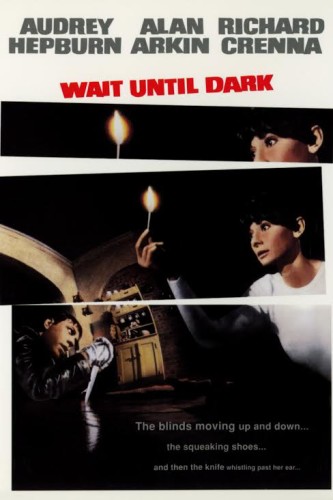

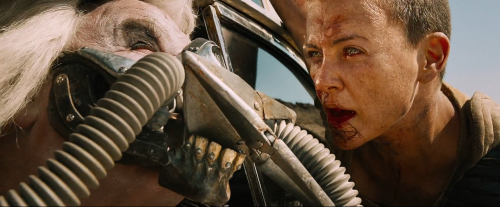

“She Called Them Anti-Seed”: How the Women of Mad Max: Fury Road Divorce Violence from Strength by Cate Young

In Mad Max: Fury Road the “strong female characters” are notable specifically for their aversion to violence. The film portrays its women as emotionally strong people who engage in violence only in self-defense, and only against the system that oppresses them.

Sugar, Spice, and Things Not Nice: Violent Girlhood in Violet & Daisy by Caroline Madden

The character of Daisy personifies the film’s juxtaposition of violence and girlhood. Daisy loves cute animals and doesn’t understand Violet’s dirty jokes. The twist is even that she has not really killed anyone, thus remaining innocent of all crimes. The opening scene displays the most daring oppositional iconography — the young girls dress as nuns, the ultimate image of pure goodness, while having a shoot ‘em up with a gang.

Children: The Great Qualifier of Female Violence by Katherine Fusciardi

True, the rape revenge trope has been put at bay, but there is still a gender issue behind the remaining motivation. It focuses around the assumption of maternity being the all-encompassing passion. Until female characters can be violent for reasons that have nothing to do with their womanhood, there still isn’t complete equality in media.

How Spring Breakers Ungenders the Erotic and Transformative Power of Violence by Emma Houxbois

The girls, driven by desperation to escape their mundane lives to take part in Spring Break, scheme a robbery of the local chicken shack to raise the necessary funds to get there. To psyche themselves up for the crime, they exhort each other to pretend it’s a video game, to detach themselves and dehumanize their victims in a hurried pep talk to the same end as the grueling boot camp scenes sequences in Full Metal Jacket.

Mad Max: Fury Road: Violence Helps Our Heroines Have a Lovely Day by Sophie Hall

Furiosa, stabbed and wounded yet still persistent, takes down the main villain Immortan Joe. “Remember me?” Furiosa growls just before ripping his breathing apparatus–and half of his face–clean off. That quip may seem like your average cool one-liner, but for me it is so much more than that. It’s Furiosa, our female protagonist, who takes out the bad guy. Not Max. Not Nux, or any other male character. Her.

Puberty and the Creation of a Monster: Ginger Snaps by Kelly Piercy

Ginger, despite morphing into a werewolf, becomes our protagonist killer in a very human way, and the complexity of her journey is a cinematic rarity. A large part of its appeal is the addictive excitement-and-relief cocktail that comes with seeing your experiences reflected on screen–to see menstruation from a menstruating perspective. Who wouldn’t see want to see the violence of their PMS daydreams being played out?

When Violence Is Excusable: Regina Mills and the Twisted Morality of Once Upon a Time by Emma Thomas

In the past, Regina’s path to control is lined with dark magic. Dark magic is fueled by her anger, and the two intersect endlessly until it is hard to tell whether Regina is controlling the anger, or the anger is controlling her. What is definitive is that the more her power grows the more violent she becomes. With the only person who offered her a loving future dead, there is no one to rein her in.

Timorous Killers: The Breach of Shyness in Polanski’s Repulsion by Johanna Mackin

The eye we see in the film’s opening credits belongs to Carol and encapsulates her relationship to the internal and external worlds. To outside observers, Carol’s large, doe-like eyes are a signifier of her feminine allure, but, as is made palpable to the viewer, they also house her intense fear and constitute a deceptive barrier against the malignant traumas that disturb her internal world.

Death of the (Male) Author: Feminist Violence in Lynne Ramsay’s Morvern Callar by Sarah Smyth

How significant it is, then, that Ramsay changes the ending from the novel where Morvern discovers she’s pregnant to instead give her a narrative of hopeful escape and adventure. Through the economic, cultural and narrative capitals gained from the violence enacted on the male author both inside and outside of the text, the female protagonist is offered a radical feminist alternative. Rather than by trapped by her class position, socio-economic position, job possibilities or pregnancy, Morvern is, instead, offered freedom, autonomy, and authority.

TV and Classic Literature: Is The 100 like Lord of the Flies? by Rowan Ellis

On the contrary, Octavia moves away from the explicit sexuality of her role in the pilot, and although her initial training is linked to Lincoln, she gravitates toward a warrior’s life to gain the respect of Indra. Although some critics have seen this as a drastic change in her characterisation, looking back at her first scene in the pilot, where she is held back by Bellamy while trying to attack the others for repeating rumours about her, it feels more like a development.

The Killer in/and the Girl: Alexandre Aja’s High Tension by Rebecca Willoughby

In High Tension, we have le tueur—the Killer—in place of the Monster, who in Shelley’s novel can be read as Victor Frankenstein’s doppelganger, that most famous of psychological devices used to illustrate the violence with which the repressed returns, doing all of the things the typical, well-socialized individual could never dream of doing. But where Victor utilizes the Monster to reject society’s expectations of him (including a traditional, heterosexual union with his adopted sister, Elizabeth), High Tension’s Marie creates le tueur because her desires do not fit within the normative world of the film.

From Ginger Snaps to Jennifer’s Body: The Contamination of Violent Women by Julia Patt

Thematically, Jennifer’s Body mirrors Ginger Snaps in many respects: the disruption of suburban or small town life, the intersection between female sexuality and violence, the close relationship between two teen girls at the films’ centers, and—perhaps most strikingly—the contagious nature of violence in women.