This is a guest post by Maria Ramos.

A woman’s domain is her home – it’s an archaic idea, but it’s one still perpetuated in today’s horror films, especially the subgenre of home invasion horror. These films serve to scare us because they take place in the one setting we’re supposed to feel safe, and their horror is much more realistic than ghosts or monsters. But how does a home invasion affect men and women so differently? In home invasion films, the female characters are often the ones trapped helplessly in their homes, making them the unlucky prisoners of their own supposed domain.

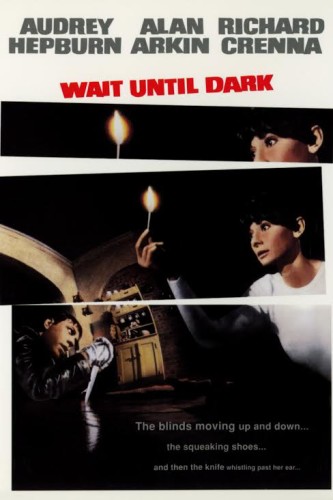

One of the most suspenseful films of all time, 1967’s Wait Until Dark, was one of the first home invasion films to hit the silver screen. It was also one of the first films to present a heroine who was absolutely helpless, even in her own home. Susy (Audrey Hepburn) is blind after a car accident, making her the perfect vulnerable target for a bunch of criminals trying to find a drug-stuffed doll that Susy’s husband may have. This film prisons Susy in her home to fend off these criminals, keeping her passive while her husband is removed from the drama. But the film’s portrayal of Susy is not negative – in fact, even though she’s vulnerable, Susy manages to outwit the criminals and show her strength when she needs it most.

In 1997, the famously misanthropic director Michael Haneke made Funny Games, one of the more brutal, violent films in the home invasion genre. Two murderous young men entrap a mother, father, and son in their vacation home to torture and eventually murder them with their sadistic games. Anna is the last surviving victim, forced to watch the brutal slaughter of her husband and son before she herself is killed. Funny Games plays into sexist ideas of women in that it does now allow Anna any agency at the end – she is not allowed to fight for her life at all.

Sometimes female characters are put into situations that limit their agency, but they end up outwitting the foes in their path to come out on top. This is the case in 2002’s Panic Room. The two main victims are a mother and daughter who are trying to make a life for themselves after a rough divorce. The film initially makes Meg (Jodie Foster) out to be a woman scorned, angry about her failed marriage and trying to win the trust of her daughter (Kristen Stewart), but once the burglars break through their security system and enter the home, she must fight to survive in the titular panic room. This enclosed space offers no communication to the outside, making it both a literal and metaphorical prison for Meg – she’s trapped, and the only way out is through violence.

In other cases, home invasion films seem to want to keep women in roles lacking agency. In 2008’s The Strangers, a couple on the verge of a breakup must face an intense night battling a group of masked killers who keep finding their way into the house. James, the boyfriend, is the one who consistently takes action while Kristen, his girlfriend, is left screaming and hiding. He’s the one who shoots the gun and calls the shots, and when he can no longer help, Kristen is totally helpless. This is an example of a film that perpetuates the stereotype of the woman who cannot fend for herself.

Luckily, the past few years have given us horror films with kick-ass heroines who can fend for themselves. In 2011, Sharni Vinson played a survivalist “final girl” in You’re Next who refused to let a group of masked killers assault her in her boyfriend’s country home. Even though the odds were against her, she used her wits and courage to get herself out of trouble, proving that home invasion films don’t always have to trap their heroines in an inescapable situation. However, it’s almost inevitable that the horror genre will continue to perpetuate stereotypes of women and place them in vulnerable roles and in inescapable situations of unnecessary violence. Let’s just hope we’ll see at least some films that go against this outdated trope.

Maria Ramos is a writer interested in comic books, cycling, and horror films. Her hobbies include cooking, doodling, and finding local shops around the city. She currently lives in Chicago with her two pet turtles, Franklin and Roy. You can follow her on Twitter @MariaRamos1889.