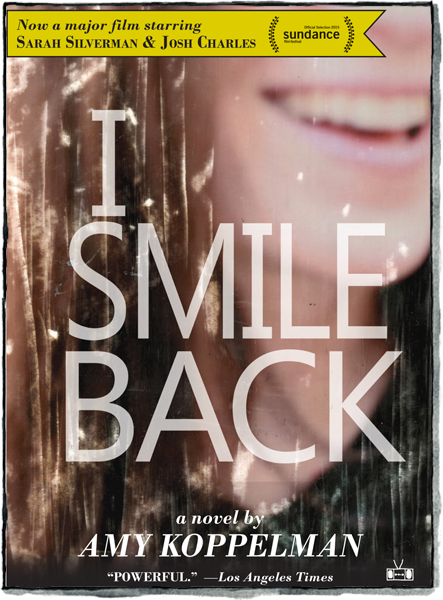

Amy Koppelman didn’t have an easy time getting her second novel published, and it’s not too difficult to understand why. I Smile Back is a painfully blunt look at living with mental illness and addiction, and takes place largely inside the head of Laney (Sarah Silverman), a well-to-do stay-at-home mom whose husband, Bruce (Josh Charles), is making a fortune in insurance. It’s clear that Bruce loves Laney, and her elementary school-aged children, Eli (Skylar Gaertner) and Janey (Shayne Coleman), need her. Abandoned as a child by her own father, Laney struggles mightily with the day-to-day responsibilities of parenting and being a partner. She finds herself drawn to illicit sex, drugs, and turmoil. She seems to have everything, so it’s sometimes difficult to empathize with her plight.

Reading Koppelman’s poetic prose, with its heavy use of repetition, metaphor, and ellipsis, and its painstaking exploration of Laney’s unhinged mind, one doesn’t think, “Hey, this would make a good movie!” So it’s surprising that it does, in no small part thanks to Silverman’s raw performance.

Koppelman co-wrote the screenplay for the independent film adaptation of her novel, and the movie, directed by Adam Salky, is every bit as brutal as the book, if not more so. I spoke with Koppelman about how the unlikely film project came about, about its unique power, and about her new novel, Hesitation Wounds, which came out earlier this month.

Bitch Flicks: I heard a little bit about how this happened, how this turned into a film. I was hoping you could talk a little about that.

Amy Koppelman: I was driving up the West Side Highway to pick my son up from school. This was around five years ago, and I heard Sarah on the Howard Stern Show, and she was talking about her new book, her memoir [The Bedwetter], and she was talking about sadness. Or she was talking about loneliness and a sense of home. I think. This is what I remember. And I remember thinking, she’s gonna understand Laney. I have to get this book to her. I think all of us, whether you’re a writer or a carpenter — just as a human being — you just wanna be understood. So the whole project started with me wanting to get the book to her, because I knew she would understand what I was trying to say with Laney. And the miracle is that she opened it, and read it. And a couple of months later, we met at a hotel for coffee, and I was looking at her, and I just said, “If I adapted this, would you…” — and I think she felt bad for me cuz, you know, it was a paperback original. I couldn’t get a hardcover. The book was rejected over 80 times — “Would you consider acting in this?” And I think she just said, “Sure!” to be nice to me, because I remember going home and telling my husband, “Well, she was just humoring me.” But she said, “If it doesn’t suck.” And so I called my screenwriting partner, Paige Dylan. That was a bar I thought we could achieve. The “If it doesn’t suck” bar. That was how it started. It was written for her. Only for her.

When you’re writing a book like this… It certainly doesn’t strike me as something like “Oh! she knew this was gonna be a film from the beginning,” because so much of it is internal, in Laney’s head.

I never write thinking about things becoming movies. It was just one of those things. A couple of times in your life, you’ll experience magic. Maybe you’ll fall in love, or… and I just heard her, and it was really just one of those moments. I just thought, no, we can figure this out. Anything that’s lost in terms of internal dialogue, the amazing thing is that you can see it in her eyes. Every nuance comes out in Sarah’s performance.

The film, to me, almost seems a little bit harsher than the book.

You read the book?! Oh my God!

Yes, after I saw the movie I read the book.

And you thought the movie was more harsh?

Yes. Perhaps because it’s Josh Charles, and there’s something innately more sympathetic about.. You know, just seeing him. You want to like him. So her distance from him, her betrayal of him feels…

Right. Well, you can’t turn away in a movie.

That’s true, too.

And yes, he has the most compassionate eyes. It’s funny, the movie was done for only $400,000 so we only had one read-through and one like soup lunch to talk about it. His only real note was, what kind of man, if you really love your husband, would see your wife in the state that Laney’s in at the end of the film, and not help her? And I do think that you see, and you understand in the film, with him not going to her and helping her, how he had to make that decision. And I think in a way that’s more harsh, because in the book he doesn’t have the opportunity to say goodbye or not say goodbye. She makes the decision. I think for anybody who’s loved a person like Laney, they’re usually a very magnetic person, and somebody that’s really fun to be with, and when they’re up, there’s no one more exciting. So I think you hold onto the hope that that’s who they are, and if you love them enough, and you give them enough stability, that you can make them better. And I think in his eyes, you see him realizing that he has to protect his family, and he can’t make her better. I never thought about it. That’s why it’s more harsh. I always thought it was maybe because in the book there’s a little more humor? But it is because you realize… you see in him, he can’t fix her.

I hadn’t read the book yet when I saw the movie, but it hit me very hard. I’ve seen movies about people struggling with addiction and depression, and was wondering why I Smile Back has this power to it. And I think a lot of our expectations for a film like this are sort of gendered. If this was a film where the main character was a man, maybe we would expect it to have a different arc. Without realizing it, I really expected it to have a redemptive arc, because she’s a mom, and I think partly because she’s a woman, I thought she was going to get it together at the end for her kids. So that was harder.

I think that’s why she’s a very hard character to like. Because women, particularly moms who do the things that she does… A man who goes to Vegas and sleeps with some hooker to blow off steam, or has an affair with his secretary, I think we understand that. We almost forgive that to a certain extent. Not the case-by-case thing. You’ll say to your friend if that happens, “What a dick,” but I think societally we understand that much more than we understand a woman who has a loving husband who’s kind to her — who she loves — just fucking to escape. That’s still a taboo. Women are not supposed to fuck to escape. They’re supposed to have a need that’s nurturing, so I think that’s very hard for the Laney character. It was very important to me in the book, and as we were writing the movie, the thing that was most important to me was that you would know that Laney loved her children and loved Bruce, and she still loved them — for a while the book had a horrible title — I think it was called “A Single Act of Kindness” because in her mind she thought she was doing them a favor. I think we think that she’s going to be able to stay with her children because she loves them, but she can’t figure it out.

I think that’s how it really is for a lot of people, so I appreciated the brutal honesty of it.

Yeah. That’s good. It’s not for everybody.

Yeah. I guess not. It’s the kind of thing I like, if it’s about a real struggle that people go through and it reflects what that’s actually like.

Redemption is always something that comes up, and I never understand that — why we need to find redemption or have redemption in books or movies. I know for me, when I can read something or see something that’s able to articulate feelings or thoughts that I’ve had that I haven’t been able to access the words for, it gives me such a sense of relief. It makes me feel so much less lonely. And so that’s where I find redemption. The idea of a quick fix redemption, I’ve never gotten anything out of that.

That’s a very Hollywood thing, though. I guess if this was a studio film, there would have been pressure to include that. There wasn’t anything like that, was there?

No. Somebody asked Mike Harrop, the producer, who was great, “Did you feel pressure to change the ending?” And he had such a good answer. He said, “We always knew the movie we were making wasn’t going to be for everybody, so we made it on a budget that could sustain itself.” I do think it’s funny. When you asked me about the beginning. I do read reviews that say “this is an obvious play for Sarah Silverman to make–” I laugh because no, that wasn’t what any of it was. She really just did us a favor really, and for some reason just let this part of herself be exposed. There was no calculation behind it. It was a little tiny movie.

I’m a big fan of hers, so I was not surprised that she was so good in it, and it never occurred to me that this was some sort of calculated career move.

Yeah, but that’s the sort of snarky reviewers would say “Well, this time of year we get the addiction…” and I just think, if that makes you feel better, to look at it that way…

It also seems too small. It’s a low budget film, and she’s not — I think she’s great in the film, but she’s not the kind of name actor — It’s not Richard Gere playing a homeless guy.

There’s not a big Hollywood machine behind it, or even a big quasi-independent studio machine behind it. It just was a movie that should hopefully find the right audience of people who understand it and who will in some way feel less lonely, or less alone, whether they’re like Laney, or they love somebody like Laney.

Do you want to talk about how much of the book is rooted in personal experience?

The books that I write are very personal, in the sense that all the self-loathing and doubt and sadness and fear — those are all mine. All the ugliness of thought. But I don’t do any of the things that Laney does. As I say, I’ve been sleeping with the same guy for 25 years, and the only drugs I do are Zoloft and Wellbutrin. Thank God for Zoloft and Wellbutrin. [laughs]

Of course, yeah. There’s so much discussion about representation in the media. Do you feel any sense of responsibility to represent women in a particular way?

It’s the only area in my life where I am 100% pure. I write these little tiny books. I know that the chances of them getting published are small, so I don’t think about those things. I just think about being honest.

I wanted to ask you about your new book, Hesitation Wounds.

Thanks. Hesitation Wounds has the most of me in it, and I really care about the book, and I’m really scared that no one’s gonna review it, so no one’s gonna know about it. [laughs] It’s about a woman who specializes in treatment-resistant psychology, so she’s the last stop on the crazy train when the regular doctors can’t figure out the correct chemical cocktail, you go to her, and you hope that she can figure it out. She does a lot of electroshock therapy, and she gets this one patient, Jim, who reminds her of her brother. She’s forced to realize how much of her life she has not really allowed herself to live or to love because she’s so scared of being hurt. Her brother killed himself when she was young. I think it’s really a book about forgiveness of yourself for surviving. I think for many people who suffer from depression or alcoholism and mood disorders, getting better and surviving… I think sometimes we all feel guilty, and I think I’m scared. I know that for me, it’s been years and years since I had any real issue with depression and having to change medication, and there’s not a day that I don’t look over my shoulder wondering when it might hit me. It’s a book about living in spite of knowing that everyone you love is gonna leave you one day. But it’s worth it.