|

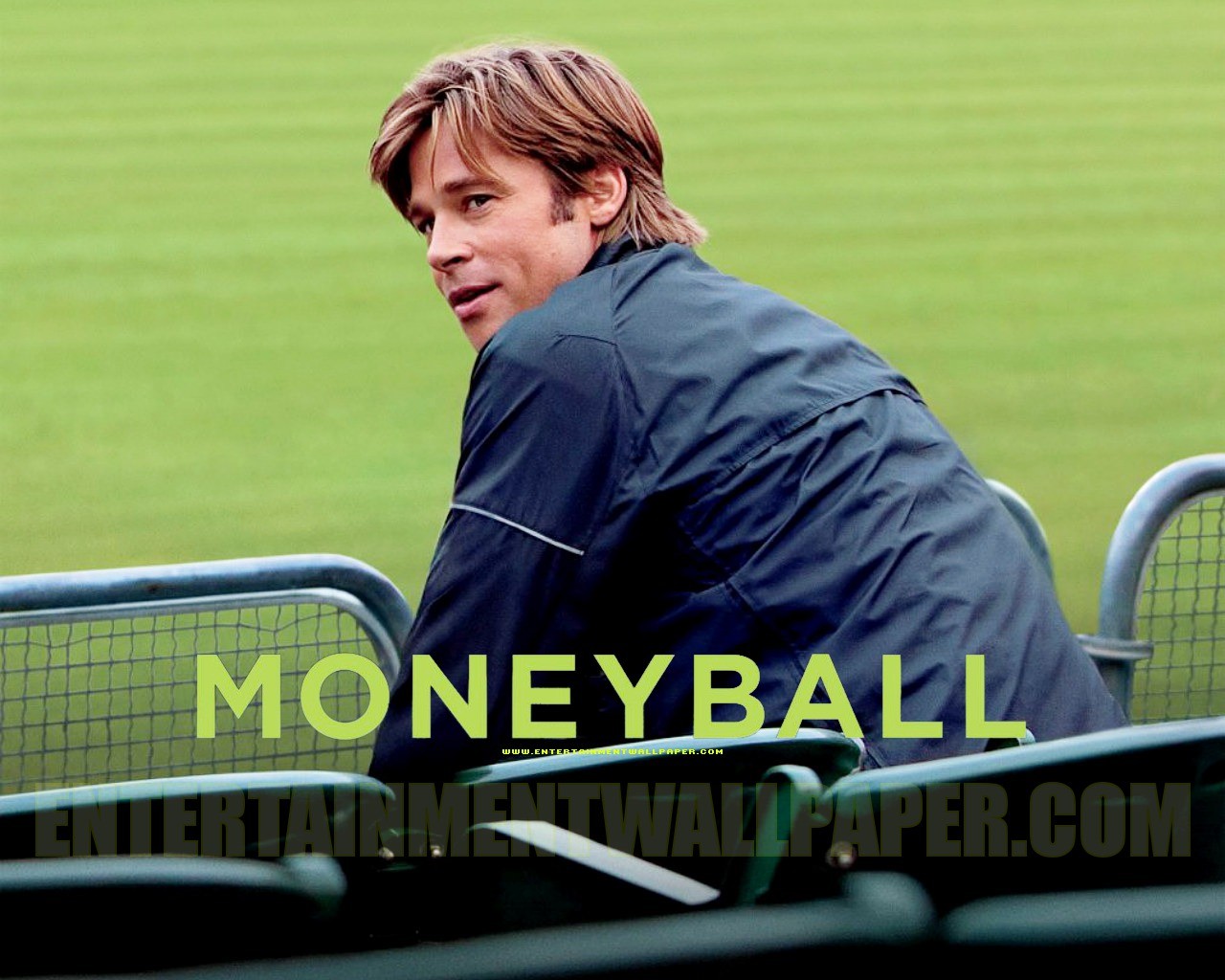

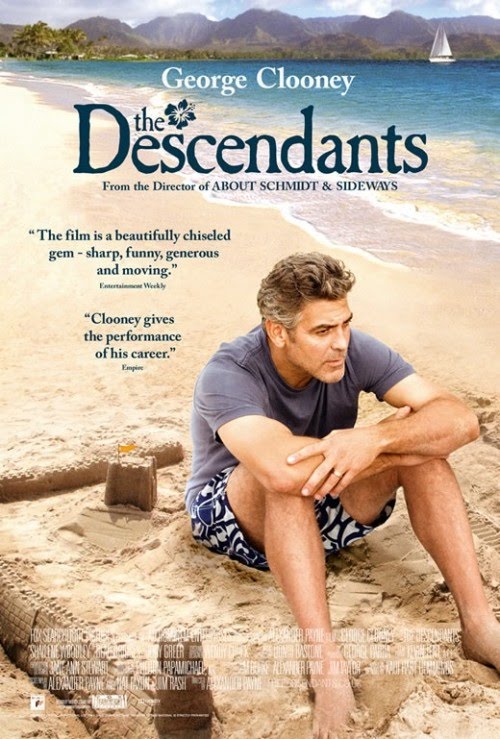

| The Descendants (2011) |

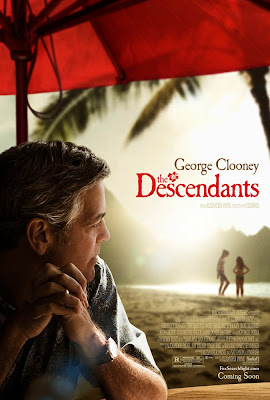

I went into The Descendants knowing only: George Clooney, land inheritance, and Hawaii. Had I even taken the time to visit IMDb and read the one-line synopsis (“A land baron tries to re-connect with his two daughters after his wife suffers a boating accident.”), I would have known a major plot element, and I might’ve been better prepared for it — and not as successfully manipulated.

The Descendants is a tricky film. You know the kind: you’re completely engrossed while watching (and I confess to being near tears for most of the film, blindsided by the emotional devastation of the situation), but once the spell of the theatre is broken, you wonder how the movie you watched is getting such astonishing praise.

|

| The King family and their land. |

That’s not to say The Descendants doesn’t have admirable elements. The film is visually stunning and offers viewers a pleasant surprise: a portrait of Hawaii (two islands specifically: Kaua’i and O’ahu) — a state of beauty and contradictions, extreme wealth and poverty, and a complicated history. Usually the Hawaiian Islands appear in film only as a vacation destination. Here, it’s something else. Not only is the setting the site of plenty of human drama, but it’s also a character in itself–similar to the role played by California’s Santa Ynez Valley in director Alexander Payne’s previous film, Sideways.

The film’s biggest problem, a fundamental mistake that I can only see as entirely unacceptable, and possibly rendering the film an utter failure (are my thoughts on the mistake clear?) is this: the character of Elizabeth King. Other than a flash of actor Patricia Hastie joyously water skiing at the beginning of the film, Elizabeth spends the rest of the film in a hospital bed, wasting away until her death. That in and of itself is not the problem; Elizabeth’s physical presence is deeply unsettling, and the details of her medical condition (the clenched hands, the life-support equipment, and the gaunt face really got to me) are rendered with disturbing realism.

But Elizabeth’s presence and all this detail comes at a price to the story: with continual reminders of the tragedy, Matt King is basically forgiven all of his transgressions and unlikable characteristics. He’s unbelievably wealthy (not particularly sympathetic in the midst of a recession) and yet a penny pincher, he’s been a terrible father and husband, and the biggest dilemma in his life is how to divide up the massive wealth his family inherited amongst his not-as-attractive cousins.

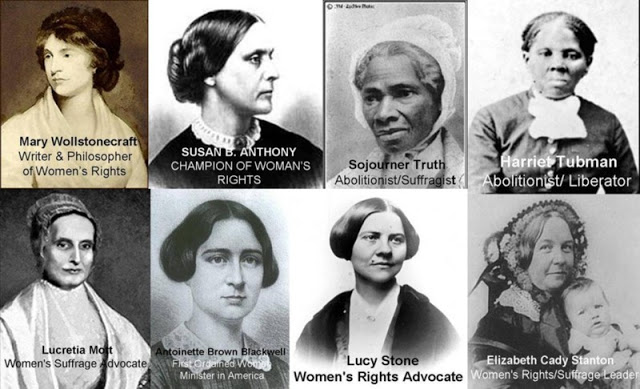

Further, Elizabeth is an example of the sexist “

Women in Refrigerators” trope. Anita Sarkeesian explains how this trope plays out in comics, television, and films:

Writers are using the Women in Refrigerators trope to literally trade a female character’s life for the benefit of a male character’s story arc.

Elizabeth’s tragic accident is the catalyst for Matt’s existential crisis…and nothing more.

Megan’s Take:

For me, I left the theatre thinking it was kind of meh. Yes, it was visually beautiful, I mean it’s Hawai’i, of course it’ll be gorgeous! And I loved the use of Hawai’ian music. But I didn’t really see what all the hype was about…except for the two daughters’ performances, especially Shailene Woodley as Matt’s rebellious (although what 17-year-old isn’t?) daughter Alex.

|

| Shailene Woodley as Alexandra King |

Absolutely outstanding, Alex stole every scene. The underwater scene blew me away. After Matt tells Alex that her mother isn’t just sick but dying, she sinks below the surface of the pool, weeping underwater…simply brilliant. Alex evoked so much pain and agony through her facial expressions and her body language, without ever uttering a word. She collapsed onto herself as her world began to crumble. Then she pushes against the pain and rage. For me, that heart-wrenching scene is hands down the best in the film.

I also found it really interesting that Alex realizes that she fights with her mother so vehemently yet she’s exactly like her mother. She rebels against authority and constraints, just like her mother. But Alex also resents her mother for cheating on her father. Mother-daughter relationships are so rarely depicted accurately on-screen. It would have been great if we could have seen more of their relationship in flashbacks. Alex appears to be the moral compass of the film. She has a zero bullshit meter and nothing gets past her. Even at such a young age, she’s like a parent to her father, telling him about the infidelity and advising him on how to handle her little sister Scottie (Amara Miller).

My favorite parts were the ones with Alex or Scottie or the two together. I loved when Scottie tosses the lawn chairs in the pool as Matt talks on the phone. There were a couple other humorous, and at times bittersweet, moments, like when Matt says, “Paradise? Paradise can go fuck itself,” Matt running in flip flops, and when Scottie calls Alex a “motherless whore” (not a huge fan of using the word “whore” but her delivery was flawless) and she accusingly points to Alex after Matt asks her where she learned to talk like that. But the film squanders these rare moments.

I felt like that was The Descendants’ problem. It never focused on what I wanted it to focus on (as if I’m the only audience that matters…ha!). The film glosses over issues of wealth/class and race/ethnicity, never really exploring these crucial societal themes. Additionally, a massive gender problem plagues the film.

Amber, it’s so interesting you mention Elizabeth and the “women in refrigerators” trope. I hadn’t even really thought about it while watching. But you’re totally right. It disturbed me how the film tried to dismantle her perfection. Elizabeth’s father tells Matt she was a perfect wife to him, not knowing about Elizabeth’s infidelity as the audience does. Her friends talk about her with such reverence as being fun and fearless. And of course no one is perfect. But I kept getting the feeling that the whole point of Elizabeth’s infidelity was to somehow excuse Matt’s bad behavior as an absentee husband and father (“I’m the backup parent, the understudy.”) Like well, see…he wasn’t that bad. At least he didn’t cheat on her like she did to him.

That’s what pissed me off about the film: its perspective and commentary on women. Matt bemoans, “What is it about me that makes women in my life want to destroy themselves?” As if the women in his life aren’t struggling with their own demons…it’s all how it affects him.

|

| George Clooney as Matt King |

Taking the “women in refrigerators” trope one step further, Jill Dolan at

The Feminist Spectator talked about how dead or dying women facilitate men’s “

self knowledge and redemption” as in the recent films

The Ides of March and

The Descendants. Even in her death, it isn’t really about Elizabeth. Or her grieving daughters, or friends, or family. It only matters how it impacts her husband, another role in which Clooney plays a man facing an emotional mid-life crisis.

It’s clear director Alexander Payne didn’t want to focus on the women in the film. I know it’s Clooney, and I love him. But it still irritated me that the movie ultimately revolves around him. I know, I know…big surprise. Another movie, an Oscar contender no less, revolving around an upper class white dude.

I think The Descendants would have been so much more interesting if told from Alex’s or Scottie’s perspective. But heaven forbid Hollywood focuses on the female characters.

So, Amber…what are your thoughts on the film’s gender roles and the interactions between the female characters? What do you think about the film’s statement on fatherhood and the relationship between fathers and daughters?

Amber’s Take:

I think

Stephanie Brown does an excellent job discussing fatherhood in her Oscar review for this site. The movie’s two fathers (three if you count Brian Speer) are, in some ways, mirror images of each other: neither is particularly involved in family life, and neither seems to know his spouse or children well. Though I haven’t quite figured out what to make of Elizabeth’s mother’s absence-by-Alzheimer’s, the fact that one adult woman was fridged and another imprisoned by dementia shows at best real disinterest in women’s relationships (and hostility at worst). Perhaps the relationship between the two daughters was sidelined for similar ideological purposes.

Regardless of what we might want the movie to be about, or focus more heavily on, we’re stuck with the hero coming to terms with being a father and making what are perhaps the first serious decisions in his life: embracing his family and role as father, and keeping the land inheritance in the family (you could just say he kicks the can down the road, avoiding a decision, too). However, I think you’re spot on when you say the film couldn’t figure out what it was about (it’s not just you!).

|

| Judy Greer as Julie Speer |

I think that it’s a film that wants to be about many serious things, all while not bumming us out too much with its weight and seriousness. In this turn toward comedy–perhaps to avoid

Terms of Endearment qualities, a comparison I never considered before reading

Brown’s analysis–we see the subjects of inheritance, the accidental nature of being born into certain families, and ethnicity diminished, and we also see the women diminished. Not just in Elizabeth, or her mother, or the relationship between the two girls, but also in a minor character: Julie Speer (played by Judy Greer). There are two moments with this character that have stuck with me in the weeks since I saw the film. The first was the strange and unsettling forced kiss from Matt, a message from him about her husband’s infidelity and an outlet for his anger, the latter of which felt all about violation and…

property. The second is the moment in the hospital when Julie first encountered the woman who had fallen in love with her husband. The film didn’t allow her an earnest confrontation; the moment was turned comedic by Matt interrupting–essentially denying her the kind of catharsis she might’ve needed. What makes this moment particularly egregious is that Matt, immediately after,

was permitted a sincere, emotional, cathartic moment with her.

At almost every turn in the film, a woman was not permitted full autonomy. Except for Alex, who was permitted to be a full, complex character. What does it mean for a teenage girl to be the moral center of a story–of this specific story? I haven’t figured it out yet, but it surely doesn’t make up for the indifference and hostility toward the other women.

Megan’s Take:

I completely agree with you that having a female as the moral compass or center of the story definitely doesn’t negate the message of hostility to women. It’s a common theme as films often bestow strength and autonomy to teen female characters, as if they’re not comfortable with adult women possessing strength and wielding power.

I also agree with you about Julie Speer. I too was annoyed and I couldn’t shake the feeling that she was surrounded by men using her: her unfaithful husband Brian and Matt King and his invasive kiss. While it was incredibly uncomfortable to watch her scream at the woman who caused her pain, ripping away that opportunity felt equally cruel.

Alex is the only female character allowed autonomy. But all of the women in the film must control their emotions and behavior. Alex possesses the most freedom as she speaks her mind freely. But she must rein in her drinking/partying and hide her pain and anger, crying underwater. Scottie must stop taking pictures and saying inappropriate things to people. Matt forces her to talk to her mother to grieve. Julie must control her emotions. Elizabeth is not only chastised but vilified in absentia for her reckless actions of drinking and infidelity.

|

| The patriarch, Matt King |

While the women have their actions and emotions policed, none of the men do. Elizabeth’s father punches Alex’s friend Sid. Sid makes ridiculous comments and is ultimately rewarded by Matt coming to him for advice on his daughters. Brian Speer is fearful when he meets Matt, but it doesn’t seem like he faces any real consequences for his actions. Matt King does have to “grow up” and finally act like a father. But he’s free to behave however he chooses, following the man who had an affair with his wife, grieve however he chooses, choosing whether or not to retain his family’s land. Matt tells his daughters, even Julie how to grieve.

What message does it send that women, both as children and as adults, must stifle their emotions and urges?

Tying all the pieces of the film together – the women denied their autonomy, erasure of discussions on race and class, revolving around a male protagonist – it reinforces white patriarchy. Not patriarchy in the sense of fatherhood but rather male privilege and female oppression. Yes, Matt King evolves into a more loving and attentive father, a bittersweet transformation. Yet I can’t help but feel the underlying theme implies men can do whatever they want, be whomever they choose, while women should not only listen to the needs and heeding of men, they are punished if they don’t.

Amber Leab is a Co-Founder and Contributing Editor to Bitch Flicks.

and

and  . She’s published work in American Poetry Review, Ploughshares and The Best American Poetry series. She was awarded an NEA Fellowship in 2001 and a Breadloaf Fellowship in 2009. She has taught at UC Irvine and the University of Redlands and is a regional branch manager for OC Public Libraries in southern California.

. She’s published work in American Poetry Review, Ploughshares and The Best American Poetry series. She was awarded an NEA Fellowship in 2001 and a Breadloaf Fellowship in 2009. She has taught at UC Irvine and the University of Redlands and is a regional branch manager for OC Public Libraries in southern California.