Written by Rachael Johnson.

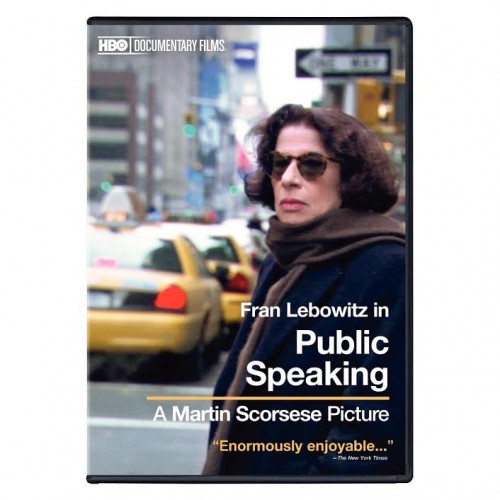

Public Speaking is an HBO documentary by Martin Scorsese about the writer and public speaker, Fran Lebowitz. Unsurprisingly, the humorist and cultural commentator makes an interesting, entertaining subject. Lebowitz’s words–as the title promises–provide the focus of the film although shots of the writer strolling the streets of Manhattan and driving in the city at night serve to add atmosphere as well as identify the writer as a quintessential New Yorker. We see Lebowitz deliver pointed observations about contemporary US culture at public speaking engagements, share the stage with the great Toni Morrison, and hold court at the famed Waverly Inn. There are, also, clips shown of a younger Lebowitz on Conan as well older television footage of the humorist at speaking and reading events. Lebowitz takes on a wide variety of topics in Public Speaking: artistic talent and genius, the New York gay and arts scenes of the 70s, present-day Manhattan, current LGBT rights issues, gender, race, writer’s block, and, yes, overgrown children in strollers. As you would expect from Scorsese, there is, also, some great footage featured. Much of it is of significant cultural figures of Lebowitz’s youth, particularly those who served as models of inspiration. There’s a great and glorious clip of the magnetic James Baldwin whom Lebowitz cites as the first intellectual she set eyes upon, although clips of Truman Capote and Gore Vidal equally fascinate.

Aesthetic influences, talent, and genius are key subjects addressed in the documentary. Although she praises the book reviews of Dorothy Parker, most of the cultural references and influences Lebowitz cites are male. She explains that “much older” gay men constituted her social and intellectual circle from the moment she arrived in the city as a young woman. Although the humorist is a friend of Toni Morrison, Scorsese does not ask why so few of Lebowitz’s influences are women, gay or straight. What has she, for example, gained intellectually and culturally from her relationship with Morrison? This is a missed opportunity.

Artistic talent is also a central theme in the documentary and Lebowitz underscores the importance of aesthetic standards as well as knowledgeable art critics: “See, what we have had in the last, like 30 years, is too much democracy in the culture, not enough democracy in the society. There’s no reason to have democracy in the culture. None. Because the culture should be made by a natural aristocracy of talent. …. By which I mean… it doesn’t have to do with, you know, what race you are, or what country you’re from, or what religion you are, it should have to do with how good are you at this thing, and that is a natural aristocracy…” Many of her observations do make a refreshing change from the self-affirming, self-stroking mantras of today’s online culture. I must admit that I laughed at her put-down of the populist appropriation of that famous Toni Morrison quote: “If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.” Lebowitz rightly reminds us, “Writers have to know things…”

Lebowitz is both a believer in cultural aristocracy and a politically liberal. She deeply laments the touristification and commercialization of New York, a city only the rich can now afford: “You cannot say that an entire city of people with lots of money is fascinating. It is not.” There’s a hilarious dig at the Bush administration to enjoy but I wish Scorsese had foregrounded and explored her progressive politics more. She has made many eloquent, passionate, dead-on statements elsewhere about America’s worship of money.

Her views on contemporary LGBT politics are, perhaps, more fully articulated in the documentary. Lebowitz provides an interesting window into 1970s New York. A young woman at the time, she was a witness to the appalling, everyday oppression of gay people during the era. She talks about gay bars being raided and customers being fired from their jobs for being gay after being named in The New York Times. She, however, takes issue with the focus of contemporary LGBT politics. Although she would vote for same-sex unions, Lebowitz finds the contemporary focus on marriage, as well as the inclusion of gay people in the military, mystifying. They are, she cries, “the two most confining institutions on the planet”. Gay marriage is, fundamentally, a civil rights issue and also, of course, a matter of individual choice yet Lebowitz has the right to ask the deeper, more politically radical question that is not commonly addressed in contemporary mainstream liberal discourse: why is gay culture embracing such a traditional institution? Some may, of course, accuse her of mocking the struggle for equality and happiness but she is not speaking out against the right. Some may also argue that Lebowitz’s stance is somewhat romantic and out-of-date in its seeming support of outsider otherness and difference? Regarding the military debate, it is outrageous that people who are willing to put themselves in harm’s way for their country can be barred from serving. Yet, from a progressive, left-wing perspective, the military is a fundamentally reactionary, right-wing institution.

Lebowitz also addresses race and sexual difference in Public Speaking. At an event in the company of Toni Morrison, she describes race as a “fantasy of superiority” and believes that it is an evil that has more hope of ending than inequality between men and women. The latter will persist, Lebowitz maintains, because of non-fantastical, “real” biological differences between the sexes. Men are naturally aggressive, courtesy of testosterone, and this gives them an “advantage”. They also seek to maintain their social dominance: “Men don’t want women to have power because they already have it. People don’t want other people to have what they have.” Contemporary, child-centered fatherhood is simply a sham for Lebowitz. It’s a “style”, she says. The humorist’s views on motherhood are equally provocative. “Women having babies is really a disadvantage. It is a disadvantage to women. ….It does kind of put you out of commission in lots of ways”, she insists. Unlike a new father, she tells an audience, a woman is “so interested” in her baby. “A woman in a room with her baby is looking at that baby. Ok? Is that who you want for your lawyer?” So then, what to make of these words? Are they not insulting to working mothers everywhere? Do they not ignore women who do not want to have babies? Lebowitz is not, of course, advocating a conservative cultural regime but I have a serious problem with her essentialist thinking here. Are these supposed “real” differences between men and women biological? While it is perfectly valid and feminist to point out the difficulties women encounter bearing and raising children in a still anti-woman society, these difficulties issue from patriarchal social structures, structures that should, of course, be changed. I do, however, agree with Lebowitz’s observations about men- or any dominant social group- refusing to give up power. I also personally believe that modern human society still blindly worships the nuclear family and that it is still fundamentally pro-natalist.

Certainly, by today’s bland standards, Lebowitz is a character. She smokes like a demon, sports Savile Row suits, and drives a Checker Marathon cab in New York City. Despite her self-confessed, aesthetic elitism and snobby digs at out-of-town “hillbilly” tourists, she does not, somehow, radiate smugness or arrogance. Despite her comments about women and babies, she also somehow manages not to come across as a Camilla Paglia-like female misogynist. She’s funny about herself, honest about her alleged extraordinary sloth-“I am the most slothful person in America,” she claims- and utterly content with her total disregard for technology.

It is perfectly valid to criticize Public Speaking as too chummy, too self-indulgent, and, simply, too New York. Lebowitz is not a household literary or comic name around the world. Nor is she one of America’s leading public intellectuals. The humorist is, however, an amusing, articulate speaker. There are things she says that viewers would question and challenge, and there are those that ring true. More often than not, her pointed wit entertains. A stimulating subject for a documentary, she would, also, no doubt, make an excellent dinner guest. And she would not be checking her iphone because she doesn’t have one.