|

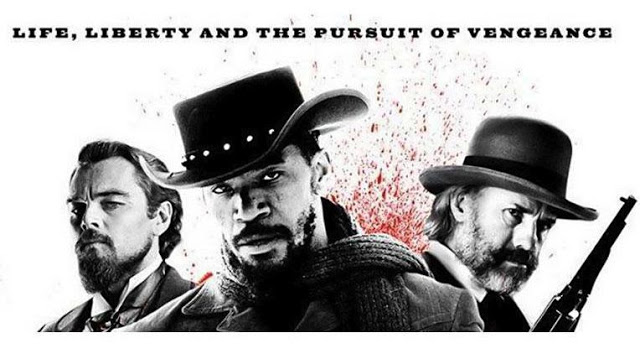

| Movie poster for Django Unchained |

However, Django Unchained, Tarantino’s eighth feature, seems to further expand his interest in exploring the intersection of cinema, history and violence, but is rather regressive in terms of female characterization.

|

| Samuel L. Jackson and Kerry Washington in Django Unchained |

Django Unchained is a powerful statement on the absurdity and cruelty that underpinned and perpetuated American slavery. The film follows Django, a freed slave played by Jamie Foxx, and his German partner, Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz) as they attempt to liberate Django’s wife, Broomhilda (Kerry Washington), from the plantation run by Leonardo DiCaprio’s odious Calvin Candie. It includes the kind of Tarantino-esque irreverence and visual wit that are familiar from his earlier films, but also manages to treat the suffering visited on enslaved African American bodies, minds, and families with respect and horror.

Django unquestionably riffs on the same sort of cinematic revenge fantasies for historical injustice that led to the explosive conclusion of Inglourious Basterds, as well as the spaghetti westerns from which Django borrows its title and main character’s name. However, the film also cites captivity narratives, which is a progressive move racially, but not in terms of gender.

|

| Leonardo DiCaprio in Django Unchained |

Broomhilda does not have such an unusual name by accident. As Schultz informs Django, and the audience, Broomhilda is a figure from Norse folklore, imprisoned on a mountaintop by her father Odin, and destined to remain trapped until her true love slays a dragon and walks through hellfire to save her. By applying this mythology to Django’s quest to free his own Broomhilda from her hellish captivity, Tarantino universalizes, and thereby de-racializes, the legend. But in so doing, he also by necessity equates the enslaved Broomhilda with the Valkyrie princess. And though both Broomhildas are, as the etymology of their name suggests, “ready for battle,” Kerry Washington is given little fighting to do onscreen in Tarantino’s script.

|

| Jamie Foxx and Kerry Washington in Django Unchained |

The first glimpse the audience gets of Broomhilda (outside of Django’s idealized hallucinations of her bathing with him and walking beside his horse in a beautiful gown) is her naked, shaking body being exhumed from “the hot box”—an outside coffin in which she was chained for running away. During a dinner party, after she has learned of Django and Schultz’s plan to trick Candie into selling her, she is stripped to the waist in the dining room to reveal her whipping scars. Broomhilda’s obvious unease during this dinner party tips off Stephen, the head house slave chillingly played by Samuel L. Jackson, to her previous relationship with Django, thereby torpedoing the surreptitious plan. During the ensuing shoot-out she is passed from male hand to male hand, and ultimately thrown onto a bed in a shack, presumably awaiting sexual violation. After Django rescues his wife and destroys Candie’s “big house,” she claps in girlish glee. A warrior queen this Broomhilda is not allowed to be, at least not during the action of the film.

|

| Jamie Foxx in Django Unchained |