| Save the Date! |

It’s Braggin’ Time!

|

| The Vamps DVD cover |

|

| I fucking so instagrammed this |

Goodbye Forever, ’30 Rock’

I have never considered Liz Lemon a feminist icon of any kind, nor have I ever considered 30 Rock especially strong when it comes to gender politics.I don’t care for the obsessive joke-making about how Liz is ugly/mannish/old/awkward, and I haven’t always been comfortable with the way some of the “she’s baby-crazy!” or “she’s relationship-crazy!” comedy has played. …And yet, I think it’s been one of the most important, helpful, meaningful, landscape-altering shows for women in the history of television.

Bitch Flicks’ Weekly Picks

Women and Minorities Snubbed by TV Academy’s Hall of Fame by Chris Beachum via Gold Derby

Lena Dunham and Democratic Nudity by Ta-Nehisi Coates via The Atlantic

Diablo Cody on the Challenge of Directing While Raising a Toddler, and Women in Film (Q&A) by Jordan Zakarin via The Hollywood Reporter

The Liz Lemon Effect by Jen Chaney via Slate

An Observation by Melissa McEwan via Shakesville

2013 Women-Created TV Pilots by Karensa Cadenas via Women and Hollywood

“Girls,” “Scandal,” and TV’s New Crop of Flawed Women by Sarah Seltzer via RH Reality Check

Bollywood Actress Sonam Kapoor on Women’s Portrayal in Indian Movies by Nyay Bhushan via The Hollywood Reporter

Feminism, King Arthur, and Disney Come Together in ‘Avalon High’ by Margot Magowan via Reel Girl

Reel Girl’s Gallery of Girls Gone Missing from Children’s Movies in 2013 via Women and Hollywood

What ‘Girls’ and ‘Shameless’ Teach Us about Being Broke, and Being Poor by Nona Willis Aronowitz via The Nation

Sundance 2013: Female Directors Discuss the Challenges They Face by John Horn via The Los Angeles Times

2012 Celluloid Ceiling Study Results Are In. Spoiler Alert: They Aren’t Great by Melissa Silverstein and Karensa Cadenas via Women and Hollywood

Where Are the Girls in Children’s Media? by Laura Beck via Jezebel

Chatting With Diablo Cody About Film, Feminism, and the Right to Be Mediocre by Katrina Pallop via Bust Magazine

‘Mama’ Tackles the Psychotic Mother Trope and Makes It Less Problematic in the Process by Alex Cranz via FemPop

MTV’s ‘Catfish’ Show Tackles Fake Online Profiles, Villainizes Transgender Women: #Fail by Breanne Harris via QWOC Media

‘Girl with the Dragon Tattoo’ Sequel Could Ditch Daniel Craig, Feature Female Lead Instead by Jill Pantozzi via The Mary Sue

Hollywood — Don’t They Want the Money? by Martha Lauzen via Women’s Media Center

A Black Feminist Comment on ‘The Sisterhood,’ the Black Church, Rachetness, and Geist by Tamura A. Lomax via Racialicious

5 Female Characters Who Should Star in ‘Star Wars Episode VII’ by Alyssa Rosenberg via ThinkProgress

Thank You, Liz Lemon, for Being You by Madeleine Davies via Jezebel

Call for Writers: Women of Color in Film & TV Week

The Color Purple

Dreamgirls

Scandal

Middle of Nowhere

Frida

The Mindy Project

Pariah

What’s Love Got to Do with It?

The Cosby Show

Precious

Lady Sings the Blues

Daughters of the Dust

Selena

Night Catches Us

Grey’s Anatomy

Real Women Have Curves

Eve’s Bayou

Mi Vida Loca

Do the Right Thing

Columbiana

Diary of a Mad Black Woman

Bend It Like Beckham

Good Times

Crash

Sparkle

Watermelon Woman

American Family

A Different World

I Like It Like That

The Help

For Colored Girls

Jumping the Broom

Soul Food

Maria Full of Grace

Girlfriends

Half and Half

Love and Basketball

Brown Sugar

Ugly Betty

The Misadventures of Awkward Black Girl

The Wire

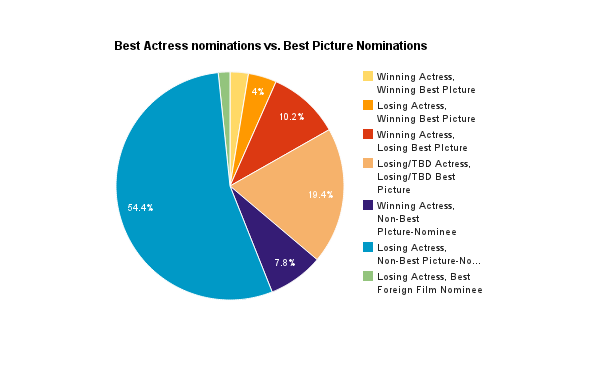

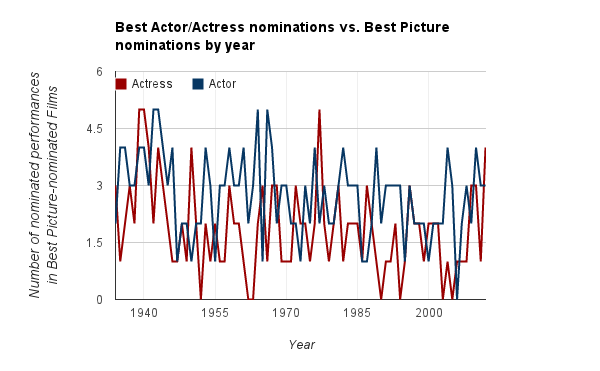

Fun with Stats: Best Actor/Actress Nominations vs. Best Picture Nominations

|

Written by Robin Hitchcock

|

| Last year’s Best Actress and Best Actor Oscar winners, Meryl Streep and Jean Dujardin. The Iron Lady was not nominated for Best Picture. The Artist was nominated for and won Best Picture. |

|

| Pie chart illustrating relationship between Best Actress nominations and Best Picture nominations |

|

| Pie Chart illustrating relationship between Best Actor nominations and Best Picture nominations |

|

| 2003 Best Actor winner Sean Penn (for Best Picture-nominated Mystic River) with 2003 Best Actress winner Charlize Theron (for non-nominated Monster). |

.png) |

| Charts showing disparity between Best Actor/Actress and Best Picture nominations over years and decades |

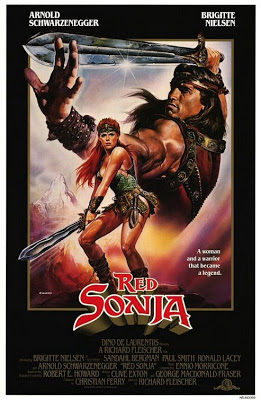

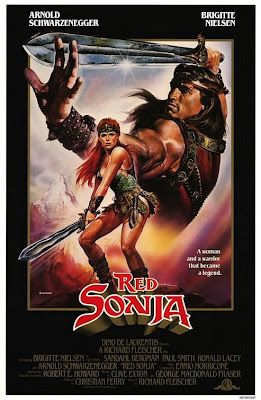

"No man may have me": ‘Red Sonja’ a Feminist Film in Disguise?

|

| Badass barbarian babes Red Sonja and Queen Gedren go head-to-head over the Talisman |

|

| Queen Gedren wears a golden mask to conceal the scar left from Red Sonja’s attack |

|

| And as usual, the evil lesbian is punished with death |

|

| Arnie muscle can’t fight the power of the Kentucky waterfall mullet |

|

Rye & Red Sonja |

———-

Go With the Flow: On-Screen Menstruation and the Crankyfest Film Festival

“Period stories are a no-brainer: There’s blood, there’s surprise, there’s drama. And more often than not, a whole lot of comedy.” – Vanessa Matsui

“The answer is clear – menstruation would become an enviable, boast-worthy, masculine event…”

“It’s an exciting time for women in the world right now – and Crankyfest is part of the wave of men and women saying ‘enough.’ Enough objectification. Enough violence. Enough of this limited portrayal of the female experience in mass media. Women are people, and they have stories. And there happen to be a ton of incredible ones about periods. Now with Crankytown and Crankyfest, there is a designated place to share those experiences, and your vision as a filmmaker.”

“In fact, if men could menstruate, the power justifications could probably go on forever.

If we let them.”

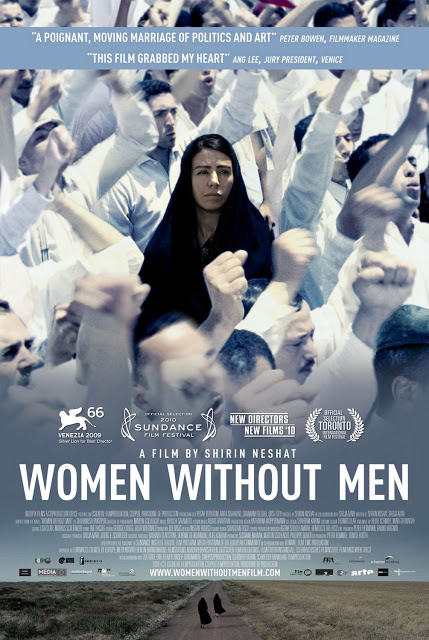

Guest Post: ‘Women Without Men’: Gender Roles in Iran, Women’s Bodies and Subverting the Male Gaze

Guest post written by Kaly Halkawt.

The author Sharnush Parsipur wrote 1989 a novel that would become what could be called a modern classic in contemporary feminist literature. The book entitled Women Without Men is a story about how five women living in Iran during the 1950s end up in exile from the male-dominated society they live in that has in different ways deprived them their freedom. Although along their path into exile is not a simple one. They must all go through a painful metamorphosis and accept that the freedom they ask for alienates their bodies from society. All five protagonists come together in a garden which serves them as a space free from male domination.

|

| A still image from the video Mahdokt |

Mahdokt’s character can here be read as a representation of the female body and an attempt to erase the values and symbols the female body has embodied in mythology as the object. Parsipur/Neshat has rewritten the myth of the female body by making it the subject and not the object of the story. Mahdokt is the narrator of her story and she is not a victim. She actively chooses to offer her body to her ideal by becoming a tree in contrast to Daphne who is a victim who is being punished for not sacrificing her body.

The film takes place in 1953 which politically is an unforgettable year in Iran’s history. The democratically chosen Prime Minister Mossadghe was overthrown by the CIA which created enormous protests. The political background story serves as a tool for creating what will be the revolution in the mind of the characters.

|

| Shabnam Toloui (Munis) |

In the first shot we see the character Munis committing suicide by jumping down from a roof, however she lives on in the story as the narrator. Later on in the film, we learn that one of the reasons for why she committed suicide was because she lived with a conservative brother who aggressively wanted her to stop following the protests by listening to the radio. He encouraged her to instead get married and “start a real life.”

The day of Munis’ suicide, we learn that her brother organized a suitable man that would come and ask for her hand in marriage. When Munis’ brother refuses to let her go out of the house, she decides to take control over the situation. By sacrificing her body for the sake of her integrity and political conviction, her death does not necessarily need to be read as a forfeit. Munis’ death leads to her freedom and becomes her politics. Its through her eyes after her death that we get to see the protests and demonstrations on the streets of Tehran.

|

| Pegah Feridony (Faezeh) |

It is also Munis action that leads to the awakening of her friend Faezeh. From the beginning, Fazeh is portrayed as a traditional girl who wants to live a “normal life” aka get married and have children with Munis’ brother. However when she finds Munis’ dead body on the street and sees how her brother digs it down in his garden to prevent the news of her suicide spreading and leading to an official shaming of the family name, Faezeh’s world is turned upside down. She gives up the idea of marriage and men and just decides to look for her own piece of mind. Munis’ ghost serves literally as the guide and takes Faezeh to the garden and leads her into exile.

|

| Arita Sharzad (Fakhri) |

Fakhri is the eldest of the gang and arguably embodies what Second Wave feminism has criticized: upper-middle class ladies who are bored serving as some sort of poupée (doll) for their husbands. Fakhri’s journey towards change starts when she meets an old friend who reminds her of the freedom that can be the price of getting married. She remembers how she used to write poetry and hang out with people who believed in culture as a political tool for change, an opinion that makes her husband laugh. So in her own “eat-pray-love” escapade, she buys a big house in the garden and leaves her relationship so that she can put energy and time into rediscovering and recreating herself.

|

| Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres’ The Turkish Bath via Amiresque |

The fourth character Zarin is a prostitute who decides to escape the brothel when she sees a client’s deranged face while they are having sex. Zarin never talks during the film and like Munis, she uses her body to free herself from the societal norms. Zarin is just her body, we don’t get her background history. I think one possible reading of why she is just reduced to a body in this film is a comment on the stereotypical images of women that have been created within the frames of Orientalism.

Some of the films key scenes are focused on Zarin. In one of the most visual scenes, Zarin is in a Turkish hamam (Turkish bath) and scrubbing her body until it starts bleeding. The misé-en-scene is an exact copy of Jean-Augustue Dominique Ingres’ painting The Turkish Bath (1862). This is a direct comment on the representational prevail of white upper-middle class men. This painting, among others, led to the creation of myths about women from the Middle East. Neshat literally tries to erase this myth in this particular scene.

|

| Orsolya Toth (Zarin) |

Another important scene that serves as a commentary for the male gaze is an image of Zarin floating in a river, alluding to John Everett Millais’ painting Ophelia (1852). In Millais’ painting, we see the suicide of Hamlet‘s Ophelia where she falls into the river and dies. Ophelia has been the subject of a lot of debate. How should we interpret her character? What values does she embody? This Shakespearian character is either referred to as a sick young damsel in distress or completely ignored and just seen as an object for male dominance in Hamlet. I think Neshat is trying to criticize the fact that Ophelia is almost never seen as her own character and only read in relation to Hamlet. Once again, Neshat tries to turn the female object into the subject.

Neshat uses Zarin’s body to criticize the stereotypical imagery of women in a few key scenes of the film by reproducing the exact same scenery as some historical paintings. However Neshat transforms Zarin’s body from object into subject, thus giving her the tools to go through a metamorphosis and take control over her body so that she can erase the values and ideas represented by men.

By giving each character their own voice to tell their story, Neshat questions the classical representation of women in Arab and Persian cultures. These women start off by being dominated in the patriarchy they live. Socially and politically, Munis is restricted by her brother. Intellectually, Fakhri does not have the freedom and the hope she had before she got married with an idiot (ie a man with power) and Zarin, before entering the garden, is just reduced to a sexual body used as a tool to control her position on a bigger scale since being a prostitute doesn’t always receive a lot of respect from society. But they all find their way to reinvent themselves in space free from male dominance. In case it’s not clear enough, this film is the queen of awesome films about women.

However one thing a bit fuzzy in Women Without Men is the portrayal of men. To sum it up, this is how Iranian men are characterized: men that live in Iran are uncultivated, uneducated rapists who crave control over women with no nuance of humanity in them. This contrasts with the Iranian men who have moved abroad, cultivated by the Western World and who see the value in educating women and treating them equally. But this is a post about the female characters so I won’t comment further other than to say the stereotype of men from Iran is not being questioned.

I never thought I would write an essay where I would find the female characters more well-written then the men. Deux point, Neshat.

Let’s All Take a Deep Breath and Calm the Fuck Down About Lena Dunham

|

| Lena Dunham and the cast of Girls |

Written by Stephanie Rogers.

I have yet to hear anyone react to the news of an advance with, “Yep, that seems about right.” It would be great if the writers and books that deserved the most money got it—ditto the same amount of attention and praise. And all the gripe-storming about how slight her book proposal was, and how she’ll never make back her advance—when did we start reviewing book proposals? When did writers start caring so passionately about publishers recouping their losses?

The entertainment industry is not a meritocracy. From before the days of Barrymore to our present age of Bacons and Bridges, Sheen-Estevezes and Zappas family has, for better and worse, equaled opportunity. The Coppola family’s connections and influence are so vast they’d make the mob envious.

I hear the diversity criticism. However, to suggest that “Girls”—a show whose charm lies in part in its documentary-like feel—presents the universe these young women inhabit, working in publishing and the arts, as rich in racial diversity, would be, sadly, to lie. Besides, did anyone ever kvetch about Jerry Seinfeld’s lack of Asian friends?

It’s cute (read: pretty hypocritical, actually) to see this sudden spike in concern over television’s portrayal of women, but this fixation is propelled by the same sense of threatened dudeness that makes a show written by and about women so “controversial” in the first place. If television were an even playing field, Dunham would not be on the cover of New York magazine atop the subheading “Girls is the ballsiest show on TV,” nor would the debut of this series be such a massive deal. (Where are the cultural dissections of CSI: Miami?) The critics calling Girls disingenuous because it stars four white women should redirect their frustration toward misogyny itself, not at the one show trying to fight it.

|

| Lena Dunham, probably getting ready to annoy people with her incessant whining |

Admittedly, I have a soft spot for Dunham, having written about her wonderful film Tiny Furniture way back in 2011, before she’d manage to offend the entire nation with her giant thighs and sloppy backside. I think she comes across as genuinely funny and interesting, and I hope that her success—and the hard hits she’s taking because of it—will make the next woman who dares to step out of line (where “line” means “the patriarchal framework”) do so with just as much fearlessness.

I mean, it’s not going to be like, “Hey guys, we’ve been out looking for a black friend or a friend in a wheelchair or a friend with a hat.” The tough thing is you kind of can’t win on that one. I have to write people who feel honest but also push our cultural ball forward.

Here’s what I think, after watching the first half hour of the season: I admire that Dunham took the criticism she got last year to heart. There are so many examples of how Hollywood ignores this type of thing. In fact, there are whole websites devoted to it. It really seems like she listened; I can’t tell from thirty minutes that everything has been solved, but it seems to be off to a good start? Lena Dunham isn’t so bad? Maybe? I say that with reservation but enthusiasm. Before I go, a couple thoughts on the good and the bad:

Good: I’ll start with positive reinforcement: Girls is definitely more diverse this season!

Bad: That definitely wasn’t the hardest thing to do.

Good: Donald Glover as Sandy! Hannah’s new, fleshed-out, not at all T-Doggy boyfriend.

Bad: I’m just hoping Donald Glover won’t simply be this show’s Charlie Wheeler.

Good: About the extras: A marked improvement in the representation of Brooklyn’s racial mix. So, Lena Dunham created a popular show, a critically acclaimed show, and instead of being, like, “Whatever. They’re all going to watch me anyway!” she actually made an effort to improve her show. That’s good. Very good. And to be honest, she probably realizes that a more realistic mix equals a more realistic world for her characters to live in.

Bad: Again, this is about the extras: There are definitely more black people on the show, but … I mean … I’ll put it this way. Realistic diversity is definitely not in your first season, girl. But it also not this. It’s definitely realistic here. But—it’s not this either, so don’t go overboard.

|

| White Women |

Laura Bennett at The New Republic said this:

Dunham uses the Sandy plot line as an opportunity to skewer both the complaints of her critics—Hannah herself echoes them with the misguided assumption that her essays are “for everyone”—and her characters’ blinkered worldview. Glover’s arc on the show is brief, but he is key to illustrating the limited scope of Hannah’s experience. “This always happens,” Sandy tells Hannah during their fight. “I’m a white girl and I moved to New York and I’m having a great time and oh I’ve got a fixed gear bike and I’m gonna date a black guy and we’re gonna go to a dangerous part of town. All that bullshit. I’ve seen it happen. And then they can’t deal with who I am.” Hannah responds with an explosion of goofy knee-jerk progressivism: “You know what, honestly maybe you should think about the fact that you could be fetishizing me. Because how many white women have you dated? Maybe you think of us as one big white blobby mass with stupid ideas. So why don’t you lay this thing down, flip it, and reverse it.” “You just said a Missy Elliot lyric,” Sandy says wearily.

It is wholly unsubtle, but it is still “Girls” at its best, at once affectionate and credible and lightly parodic. There is Hannah: impulsive, oblivious, tangled up in her own sloppy self-justifications. And then there is Lena Dunham, the wary third eye hovering above the action. “The joke’s on you because you know what? I never thought about the fact that you were black once,” Hannah tells Sandy. “I don’t live in a world where there are divisions like this,” she says. His simple reply: “You do.”

And I find myself back at the same place I was when Maya and I talked about Beyonce. No, Dunham’s attempt to introduce racial discourse into her show doesn’t suddenly make it diverse, but I think she still deserves some credit. If it sounds like I’m saying: the white girl gets a pass for not painting an accurate portrait of Blackness because she doesn’t have lived context/experience, that’s exactly what I’m saying. Why do we expect “all or nothing” from anyone who dares to align themselves with a few feminist values, even if they don’t call themselves feminists? When will we begin the process of meeting people where they are?

And, as Samhita wrote on this topic, maybe we should spend less time “scrutinizing [Dunham’s] personal behavior instead of looking at the real problem—the lack of diverse representations of women in popular culture.” Do we need to see realistic representations of Black girlhood on television? Yes, that’s why we need more Black girls writing shows. *raises hand* Do we need examples of diversity in film? Yes, that’s why we need more people from diverse backgrounds writing them. Truthfully, I’d rather not leave that task up to a white girl with “no Black friends.”

|

| Lena Dunham, being all entitled and shit |

|

| “Eh, what are you gonna do?” –privileged White dudes everywhere, in response to rarely getting called out for their bullshit |

When Dumb Fun Turns Nasty: Sexual Violence in Stupid Movies

|

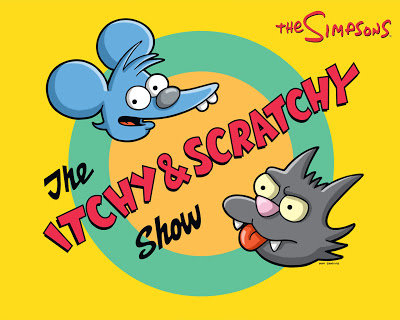

| And I respond just like Bart and Lisa Simpson. |

|

|

Goddammit, it’s called Nazis at the Center of the Earth, not Rapists at the Center of the Earth.

|

|

|

If you’re more of a words person, this might help.

|

Classic Literature Film Adaptations Week: The Roundup

“The Depiction of Women in Three Films Based on the Fairy Tales of Hans Christian Andersen” by Alisande Fitzsimons

“The Depiction of Women in Three Films Based on the Fairy Tales of Hans Christian Andersen” by Alisande Fitzsimons

“Ballet Shoes“ by Max Thornton

“For Colored Girls Reveals Power of Sisterly Solidarity & Women Finding Their Voice” by Megan Kearns

“Farewell My Concubine“ by René Kluge

“A New Jane in Cary Fukunaga’s Jane Eyre (2011)” by Rhea Daniel

“‘John Would Think It Absurd’: How ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ Fails in Translation to the Screen” by Marcia Herring

“Hellraisers in Hoop Skirts: Gillian Armstrong’s Proudly Feminist Little Women“ by Jessica Freeman-Slade

“A Love Letter to Anne of Green Gables“ by Megan Kearns

“Titus the Tight-Ass: Julie Taymor’s Depictions of the Virgin and Whore” by Amanda Rodriguez

“Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston” by Martyna Przybysz

“The Uninvited (1944) and Dorothy Macardle’s Feminism” by Nadia Smith

“Helen Mirren Stars in Julie Taymor’s Gender-Bent The Tempest“ by Amber Leab

“Slut-Shaming in the 1700s: Dangerous Liaisons and Cruel Intentions“ by Jessica Freeman-Slade

“How BBC’s Pride & Prejudice Illustrates Why the Regency Period Sucked for Women” by Myrna Waldron

“Comparing Two Versions of Pride and Prejudice“ by Lady T

“Gendered Values and Women in Middle Earth” by Barrett Vann

“Shades of Feminism in Othello“ by Leigh Kolb

“The Tragedy of Masculinity in Romeo + Juliet“ by Leigh Kolb

“Mrs. Danvers, or: Rebecca“ by Amanda Civitello

“We Need to Talk About Kevin“ by Amanda Lyons

.png)