“The Depiction of Women in Three Films Based on the Fairy Tales of Hans Christian Andersen” by Alisande Fitzsimons

“The Depiction of Women in Three Films Based on the Fairy Tales of Hans Christian Andersen” by Alisande Fitzsimons

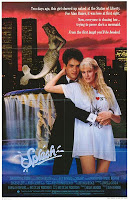

I rather like this ending to a film because despite not sticking to the original story, it offers viewers a chance to see something that is still relatively unusual on-screen: a successful male character giving up his life for the woman (mermaid) he loves. He sacrifices everything for her, with no real guarantee that he’ll be happy, and absolutely no way back. In that way, the male lead (Tom Hanks) is more like the little mermaid of HCA’s original story, who gave up her life below the sea for the human she loved, than Daryl Hannah’s character.

“Ballet Shoes“ by Max Thornton

Much of the story’s genius lies in the characterization of the three sisters. Beautiful Pauline is a talented actress who feels the responsibility of being the eldest sibling; dreamy, waifish Posy thinks of nothing but dancing, to the point of complete otherworldliness; Petrova is the tomboy, the middle child, and the odd one out, who loathes being onstage and is happiest around engines. This set-up creates a lovely interplay of strong, distinct personalities who are united by the loyal bonds of sisterhood, which is really the heart of the story.

“For Colored Girls Reveals Power of Sisterly Solidarity & Women Finding Their Voice” by Megan Kearns

The theme of a woman’s voice echoes throughout the film. Women being silenced…by shame, fear, abuse, their mothers, the men in their lives, society…is threaded throughout. Shange’s play and Perry’s film testify the power of women finding solace, self-acceptance and strength in themselves and reclaiming their voice. It’s time we listened to women’s voices and hear what they have to say.

“Farewell My Concubine“ by René Kluge

A gender conscious reading of Farewell hence raises a question that seems to play a big role in many contributions on Bitch Flicks: In light of a film history that has in big part either ignored women or made them the objects of the male gaze, is the sheer visibility of women and/or trans* people already a step forward, or must we pay closer attention to the substance of the representation? This is a question that is not easy to answer, especially for me being a white heterosexual male with no shortage of role models and media idols. Maybe this question is actually very personal and revokes an abstract theoretical analysis. Maybe every female, trans* and/or homosexual person has to choose for her/himself. If they can relate to Dieyi or Juxian, identify with them and understand their personal emancipation and empowerment through them, then no detached scholarly interpretation could argue with that.

“A New Jane in Cary Fukunaga’s Jane Eyre (2011)” by Rhea Daniel

The central story of the complex lone woman, unloved and unwanted–matched with the world-weary hero set in a background that’s far from sumptuous–is in great danger of turning into a great depressing drag of a tale, so it’s incredibly important for that spark and pull between them to work. The script by Moira Buffini aids this, taking only the relevant bits from the novel and chipping away at them so that they shine at the significant parts of the movie, avoiding the verbal diarrhea that can come with being loyal to a classic novel.

“‘John Would Think It Absurd’: How ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ Fails in Translation to the Screen” by Marcia Herring

One of the many lessons here is that literature, like history, has become another commodity in which the male perspective and experience is privileged. In case it was left to doubt, I do not recommend “The Yellow Wallpaper;” in fact, the scariest thing about Thomas’s “The Yellow Wallpaper” is that two men apparently read Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s short story and thought: “But what about the husband? What about the men?”

“Hellraisers in Hoop Skirts: Gillian Armstrong’s Proudly Feminist Little Women“ by Jessica Freeman-Slade

These young women talk openly about money, politics, education, love, and above all, the expectations set upon them. Jo (Ryder) drives the movie, narrates and controls its pace, and she gives the perfect period performance by a contemporary actress—in part because she doesn’t hide just how modern and unnatural she is in the heavy skirts she’s obligated to wear. She seems genuinely uncomfortable, just as Jo would be, slouching, hunching, galumphing about, talking with her mouth full, stomping her feet in the snow. Jo has bigger ambitions than to be pretty or charming: she has a bright mind, a passion for writing, and a dream of sharing her stories with the world. Ryder’s passion, the gusto with which she delivers every line, sings out, and makes this one of her best performances.

“A Love Letter to Anne of Green Gables“ by Megan Kearns

Children need role models. But girls especially need strong female role models because of the inundation of sexist and misogynistic media. Children’s (and adults’) movies and TV shows too often suffer from the Smurfette Principle, revolving around boys. In our pink sea of princess culture saturating girlhood, it’s refreshing to watch and read a bold, intelligent and unique – and feminist – character like Anne.

“Titus the Tight-Ass: Julie Taymor’s Depictions of the Virgin and Whore” by Amanda Rodriguez

Julie Taymor’s

Titus (based on Shakespeare’s

Titus Andronicus) is a highly stylized production, involving elaborate costumes, body markings, choreography, era prop mash-ups, and extravagant violence. I tip my hat to Taymor for the scope and splendor of her vision, and I also applaud her for paving the way for other talented female directors in Hollywood. Though Taymor updates much of the Shakespeare play (using cars, guns, and pool tables alongside swords, Roman robes, and Shakespearean language), Taymor does little to re-interpret the female roles in an effort to make them more progressive and complex.

“Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston” by Martyna Przybysz

Although I find it thin and slow in places, I struggle to dislike Darnell Martin’s adaptation of Hurston’s novel. After all, it manages to carry a powerful message, despite it not being in favour of the current feminist perception of gender roles and female identity. Yet remembering that it is set in the early 20th century reality of African-Americans, one has to admit that it does a fair job at depicting a woman who goes beyond her time. Even if it does so not without pretense, and in a more simplistic way than Hurston’s beautiful novel.

“The Uninvited (1944) and Dorothy Macardle’s Feminism” by Nadia Smith

Overall, The Uninvited reflects a range of tensions and negotiations that intersected with contemporary discourses about gender, sexuality, feminism, and film censorship. While it falls prey to some hostile and stereotypical female characterizations common in the 1940s and later, it is complex and multilayered enough to allow for a range of readings and interpretations as it attempted to speak the unspeakable and represent the unrepresentable.

“Helen Mirren Stars in Julie Taymor’s Gender-Bent The Tempest“ by Amber Leab

Mirren embodies Prospera with fierceness and control, sort of like she does in every role she plays–or at least in all of her performances I’ve seen. Her books, her learning, is the source of her power. Perhaps her people in Milan had a real fear of such an educated and powerful woman, and their only way to deal with her was to get rid of her. Our society still has trouble with smart and powerful women, after all.

“Slut-Shaming in the 1700s: Dangerous Liaisons and Cruel Intentions“ by Jessica Freeman-Slade

The stakes in each of these dramas are not only sexual, but obsessed with honor, power, and who gets to claim it. And in both adaptations, the performances by Close and Gellar show that it’s Merteuil’s grudges (and not Valmont’s impulses) that lay the groundwork for the sexual manipulation. It’s less than ideal to have women as such villains, but Laclos left us one of the strongest and most complex female characters in all of literature—for better or for worse—and these ladies sink their teeth into all of Merteuil’s depravity.

“How BBC’s Pride & Prejudice Illustrates Why the Regency Period Sucked for Women” by Myrna Waldron

The 6 episodes of the miniseries grant far more lenience in terms of time constraints, and thus one of the most important themes of Austen’s novel is retained: Her feminism. The protagonists in her novels were all women, and she wrote them for a mostly female audience. Her primary goal was to create sympathy for the status of women and the little rights they retained. Reminder: This is an era where women could not vote, had no bodily autonomy, could not freely marry whomever they chose, were restricted to domestic spheres, and, in some cases, could not even inherit their father’s estate. Pride & Prejudice, and the BBC adaptation, touch on several of these issues, subtly and sometimes directly condemning them from a feminist outlook. In addition to this feminist subtext, part of Austen’s social satire is pointing out the ridiculous class restraints in which the characters had to endure.

“Comparing Two Versions of Pride and Prejudice“ by Lady T

I had a bad feeling about the 2005 adaptation even before I saw it, because Keira Knightley said something in an interview comparing Darcy and Elizabeth to two teenagers who don’t realize how much they actually like each other…and that’s exactly how she plays it. It’s such a disservice to both characters, especially Elizabeth, to describe them in that way. Elizabeth’s problem is not that she’s SEKRITLY IN LUUV with Darcy from the very beginning but in denial about her feelings. Her problem is that she’s almost as arrogant as Darcy is, so impressed with herself for being a wonderful judge of character, that she doesn’t revise her opinion of him until given evidence that she’s wrong.

“Gendered Values and Women in Middle Earth” by Barrett Vann

The value system in Tolkien’s Middle Earth consistently favours “softer” strengths, putting emphasis on gentleness, scholarliness, empathy, and patience as qualities that heroes possess. Indeed, it’s written into the very mythology of the legendarium. In The Silmarillion, one of the mighty of the gods of Middle Earth is Nienna, who “is acquainted with grief, and mourns for every wound that Arda has suffered in the marring of Melkor. … But she does not weep for herself; and those who hearken to her learn pity, and endurance in hope” (Tolkien, p. 19). Gandalf in his younger days is described as having learned pity and patience from her. This value placed upon empathy, of sorrow as a virtue, endurance of the spirit rather than the body, resonates throughout all of Tolkien’s works.

“Shades of Feminism in Othello“ by Leigh Kolb

As for the feminist themes of Othello, they are clear from the very beginning. Desdemona goes behind her father’s back to marry Othello–a celebrated general but not a native Venetian (he is a “Moor,” a black man of African/Muslim descent). She goes before the senate to prove Othello didn’t win her by “witchcraft” (see: racism) and she requests to travel with him to Cyprus. She stands up to her father convincingly, and while she is dutiful to the men in her life, she clearly has an independent spirit. Parker’s Desdemona is also sexual (he includes a sex scene between Othello and Desdemona, and shows flashbacks of their courtship and intimate relationship).

“The Tragedy of Masculinity in Romeo + Juliet“ by Leigh Kolb

Juliet is continuously more mature than Romeo. While she falls for him as he does for her, she wants to know that he’s serious. Romeo stumbles, he’s clearly much more juvenile than Juliet is. They represent youth, yes, but also a departure from not only their fathers’ patriarchal social order, but also the gendered expectations placed upon them. Juliet’s world is protected and arranged for her; she’s expected to have a life like her mother’s (arranged and out of her control). Romeo’s effeminate nature goes against his father’s powerful corporate position and his cousins’ violent outbursts.

“Mrs. Danvers, or: Rebecca“ by Amanda Civitello

These perplexing editorial choices in the novel’s adaptation for the screen make for a viewing experience which leaves audiences with a distinctly different perception of the characters and the story. The viewers are denied the absolutely disquieting story of the novel. What’s so disturbing – and so Gothic – about Rebecca isn’t Rebecca herself, and not even the image of Rebecca, the spectre of her, that the different characters construct, but the moral ambiguity surrounding the characters we’re supposed to like and dislike. If a novel – or a screenplay – is meant to be a constructed world, one that functions according to its own rules, then du Maurier’s Rebecca wreaks havoc with that framework.

“We Need to Talk About Kevin“ by Amanda Lyons

And this is what was so terrifying to me about Kevin—its worst-case scenario of motherhood. The woman enslaved, powerless, first by the very presence of the baby growing inside her and then trapped in the four walls of the home, slave to a psychopathic child who is the ultimate tyrant. Disbelieved by her partner, having to cope alone, cut off from the socially accepted positive experience of motherhood. Forced to nurture a child that has nothing but hate and contempt for you.

“The Depiction of Women in Three Films Based on the Fairy Tales of Hans Christian Andersen” by Alisande Fitzsimons

“The Depiction of Women in Three Films Based on the Fairy Tales of Hans Christian Andersen” by Alisande Fitzsimons

1 thought on “Classic Literature Film Adaptations Week: The Roundup”

Comments are closed.