Written by Erin Tatum.

Queer representation has increased steadily over the past few years. Like all characters, some portrayals are better than others. It unfortunately seems to be an unspoken rule that writers have a lot more room with laziness or clichés when it comes to creating queer characters. The logic behind minority characters and particularly queer characters tends to follow the philosophy of “make ‘em as one dimensional as you want, you get a gold star for just admitting that they exist!” Thus anyone who isn’t a cis, straight, able-bodied white male has a lot of hurdles to climb. Many writers have recently expressed enthusiasm about LGBT community inclusion, which has been both a blessing and a curse. Really, how many unrequited crush storylines can you do? Often, “queer” becomes code for “resident narrative punching bag and straight romance prop.”

Nonetheless, sometimes writers strike gold. Two prime examples include Naomi Campbell (Skins) and Adam Torres (Degrassi), a lesbian and female to male (FTM) trans* guy respectively. Naomi (Lily Loveless) is everyone’s favorite snark knight with an interest in politics and a growing attraction to Emily (Kat Prescott). Naomi grapples with her sexuality, her fear of vulnerability, and fierce opposition from Emily’s twin sister Katie. After a river of tears and several passionate monologues, Naomi and Emily, aka Naomily, finally get their happy ending. They even survive a godawful love square. The queer community fell as deeply in love with Naomi and Emily as they did with each other and the couple was almost universally hailed as the most iconic queer coming-of-age story of our generation. Adam (Jordan Todosey) faces similar obstacles. Although he is confident in his identity, he faces constant opposition from his reluctant mother as well as bullying and harassment from his peers, which drives him to self-harm. He fights for everything from sports participation to bathroom rights. Adding insult to injury, he is rejected by a slew of girls because they can’t accept him as authentically male. In an ironic twist, he ultimately finds himself happy in love with an extremely conservative Christian girl, Becky (Sarah Fisher). Degrassi received tons of positive press for introducing TV’s first transgendered teen.

Of course, the characters and the execution of their representation weren’t without fault. Once you strip away all the jaded hipster dialogue and pretty outfits and tortured sexual tension, Naomily’s storyline is fairly formulaic – one person experiences perpetual gay panic while their dogged love interest gets dragged through the mud and back into the closet. Naomi’s involvement with politics only functioned as a premise for her to interact initially with Emily and then completely disappeared. Naomi and Emily’s sole purpose individually is to be hopelessly codependent on the other, so much so that most fans just refer to them by their portmanteau. They never existed outside of each other’s narratives and their relationship was the entirety of their character development. By the same token, I can’t name an Adam plot that didn’t relate directly or indirectly to him being transgendered. The fact that most of Adam’s love interests bypassed him to date his cisgendered brother Drew sends a painfully deliberate, albeit possibly unintentional, message to the audience. In spite of everything, the incredibly compelling performances of the actresses allowed these characters to transcend stereotypical stumbles and become sympathetic and relatable. Naomi and Adam were clear fan favorites.

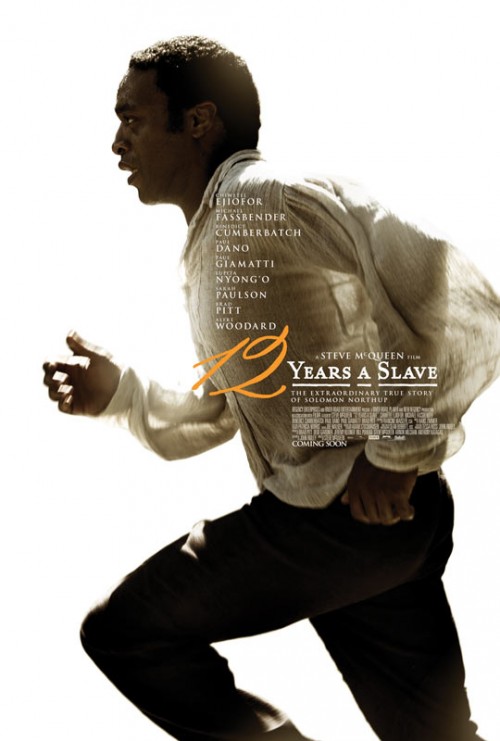

However, for some reason, the siren song of shock value makes writers unable to let sleeping dogs lie. Happiness (or let’s be real, any positivity) just isn’t authentic enough. Queer characters have a bull’s-eye on their backs because their suffering is interpreted as a commentary on the cruelty of the human condition, even if their death has nothing to do with their identity. It’s symbolic! The potential pathos payoff of a queer martyr is too tempting to worry about silly junk like the importance of representation or overcoming adversity. Queer kids, you can totally have a meaningful future, until your death is required for timely social commentary or for the sake of artistic profundity! But you still kind of sort of existed when it was relevant to other people, so isn’t that enough? Ah yes, you can always depend on that token queer waiting in the slaughterhouse when you’ve run out of ideas and/or creative integrity.

Here’s where the shit hits the fan. As a longtime devotee of both Skins and Degrassi and someone who was deeply emotionally invested in both Adam and Naomi as individuals and their potential to attest to and bring about an evolving social landscape long overdue, I’m about to get unapologetically salty. Buckle up.

Everything had turned out well for Naomi and Emily. Skins changes casts every two years, so we hadn’t seen them since 2010. The show is notoriously scant with mentions of previous characters once they’ve moved on. Fan reaction was thus understandably elated when it was announced that the couple would return for the show’s final “celebratory” season this past July, which claimed to serve as an updated epilogue for a handful of popular characters. Though Naomi and Emily were somewhat nonsensically shoehorned into an episode with another character as the main focus, everyone was excited to see what new challenges they were facing. Optimism is an Achilles’ heel when it comes to the Skins franchise because the writers conflate maturity and character development with total disillusionment and misery. Showrunners and father/son co-creators Brian Elsley and Jamie Brittain passed the torch of Naomily to little sister Jess. Nepotism is always the surefire way to have a job well done! That’s like letting your younger sister play with your favorite Barbie dolls and giving her full permission to toss them down the garbage disposal. Still, Jamie himself stated that Naomi and Emily get married in the future. The outcome couldn’t be too catastrophic, right?

Think again! Naomi and Emily are reduced to window dressing as the primary character Effy enjoys a glamorous life in the London stock investment world. Effy and Naomi are roommates while Emily does a photography internship in New York (the first time Emily has been given an interest outside of Naomi). Proving her mediocrity as a writer, Jess saddles Naomi with cancer and makes her entire plot – a B-plot for crying out loud – about the impact her illness has on Effy. We have less than an hour to get reacquainted with a character that we haven’t seen in three years, you give her a terminal illness in the B-plot, and the fucking plot isn’t even technically about her. Naomi decides to keep Emily in the dark to protect her because that’s ~the noble thing to do, alluding to their fragile trust issues after mutual infidelity. I don’t even understand why Kat was in the credits when Emily has so little screen time. Emily visits Naomi once early on in blissful ignorance and they have sex while moaning pornographically as Effy tries to get it on with her love interest. Haha, the hilarity of gay sex. Naomi then deteriorates super graphically, vomiting in Effy’s lap and eventually being confined to a hospital bed. When it’s confirmed that the unnamed cancer is terminal, Effy caves and tells Emily. The last we see of Naomily is Emily curled up sobbing by Naomi’s side, with Naomi’s fate left ambiguous but pretty much sealed.

[youtube_sc url=”http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FCSIRiLPdzk”]

The backlash was intense and venomous. Naomily was one of the few queer couples with a solidly positive ending. Sure, plenty of people would argue that their cheating storyline was weak as hell (myself included), but that was redeemed for many when Naomi won Emily back for good. The ink was dry, their chapter was closed, etc. There was no reason to mess with a good thing, save for the obvious elephant in the room: ratings and easy exploitation. Naomily was the piece de resistance of the franchise and their reputation arguably preceded and eclipsed that of the show itself. The PR team knew that Naomily fans were a large demographic. However, the ratings ploy aspect of it isn’t even that logical, since it was already announced that the series was canceled before filming on the final season started. Accusations and mudslinging began to fly. The Brittains have had a remarkably antagonistic relationship to the Skins fan base. We are talking levels of contempt that would put Ryan Murphy and the Glee fandom to shame. As the seasons wore on and the gimmicks got cheaper, fans became increasingly vocal about their disappointment. Given the Brittain’s penchant for routine, pointless character death and the immense outcry that it always provoked, Naomi’s death was seen as a blatant middle finger. Heather Hogan, AfterEllen contributor and former staunch defendant of all previous Skins fuckery due to Naomily’s flawlessness, announced that she would not be reviewing the episode precisely because it needlessly extinguished a shining example for an entire community. When you’ve lost your most irrational stan, that’s when you know you’ve shit the bed. For their part, the Brittain siblings responded to the onslaught of genuine dismay with all the grace and poise of constipated five-year-olds denied their nap time. Jess deleted her Twitter multiple times and in response to Heather calling them out on their contribution to the alarming frequency of queer women character deaths, Jamie tweeted back “I couldn’t care less.”

The wound was so deep that people vowed to turn their backs on the beloved actresses, questioning whether they knew about the outcome of the script when they signed on for the project. On one hand, it’s important to remember that actors are just doing their job and everyone has to make a living. However, the sense of betrayal definitely resonates on some level. If Lily and Kat did know that Naomi would end up on her deathbed, it’s a little depressing to think that they would be willing to self-destruct characters that launched their careers for an easy paycheck, when they themselves have spoken of the overwhelmingly positive response to and significance of Naomily. Jess defended herself by stating that even if Naomi did die, it effectively didn’t matter because Naomi and Emily would always be gay. I tried to make a joke here, but I couldn’t because the argument is too nonsensical. The stupidity transcends my wit. I didn’t know that was possible.

Adam’s departure was equally shoddy. Following the launch of his epic romance, he quickly faded into the background. Rumors were swirling for months that Jordan Todosey wanted to leave Degrassi. There were also concerns about Jordan’s shelf life as Adam, given that several of Adam’s storylines revolved around his decision to begin testosterone treatments and Jordan isn’t trans*. This is one of those instances that underscores the importance of casting someone who actually matches the character’s circumstances in real life, although Jordan’s performance was consistently strong. Normally I loathe casting multiple actors to play the same character, but on this rare occasion, it would have worked, especially since Jordan wanted to leave anyway. They could have gotten a trans* guy to take over the role post-testosterone. I should have anticipated that Adam’s actual resolution would be much more asinine.

Adam suddenly returns front and center for the early block of season 13 episodes, which should have been our first red flag. All of the previous meticulousness that had gone into making Adam look masculine has vanished and his style throughout his final return is basically just Jordan awkwardly shoved into frumpy layered flannel and baseball caps, making her look more like a lesbian suburban soccer mom than a 17-year-old boy. I know Jordan had been phoning it in with Adam and growing her hair out, but this was just embarrassing. I don’t mean to imply that trans* guys who don’t present as traditionally masculine are less legitimate, but letting Adam running around with a mullet and what appears to be unisex 80s clothing from the local Goodwill does a deep disservice to his character in that his central concern has always been passing as masculine and sometimes even cisgendered.

Anyway, what better use of Adam’s last few episodes of screen time than a gratuitous and nonsensical love triangle! The writers answered the prayers of many a fangirl in the most unsavory way possible by putting him at the center of a girl-on-girl rivalry as soon as he was in a stable and loving relationship. Long story short, Adam and Becky have a fight, prompting Adam to make out with his friend Imogen. He feels so wracked with guilt that he immediately jumps in the car and texts Becky. The distraction causes him to crash into a tree. We have the lovely treat of seeing him bruised and bandaged in a coma for all of one episode before he quietly passes away. Vomit. Fans were obviously upset. Showrunner Stefan Brogren bailed himself out by advising fans via Twitter not to watch Degrassi if they don’t like it. He must have time traveled all the way back to sixth grade to come up with that zinger. Since Adam’s death, some half-assed attempts to turn him into a sacrificial lamb for texting and driving awareness have fallen flat because a) you could’ve given that plot to any other fucking character b) are you really doubling down on PSA duty with the trans* kid? and c) his original intent in terms of “audience lessons” (if you’re going to reduce him to that) was done with such care and empathy that it makes this plot seem like a bag of horse shit. Letting him by defined postmortem by texting and driving spits on his legacy. I have the urge to insert that middle finger gif every other sentence.

In abstract, the writers’ defenses of their chosen character deaths were lazy yet plausible. The Brittains pointed out that many young people have their lives tragically cut short by cancer and Brogren essentially made the same argument for texting and driving. Both statements are true. In those situations, death does not discriminate. But you can’t sit there and honestly tell me that those decisions were pure coincidence, even if only on the unconscious level. Really, you just happened to kill the LGBT character? That’s like robbing someone’s house and then claiming that they can’t prosecute you because some burglaries go unsolved, despite the fact that you’d been scoping out their house for months and knew they were vulnerable. As for why this explanation is fucking ridiculous on a show specific level, Naomi’s appearance was anticipated to be a 45 min. ratings victory lap about what she had been up to since going to university. You could have shown her cleaning pools, for fuck’s sake, as long as she had a few cute scenes with Emily. We hadn’t seen her in three years and we aren’t ever going to see her again, so why on earth would you choose to nuke the crown jewel of your family franchise with a cliché cancer tragedy fapfest? On a similar note, Degrassi has been known for writing off characters in as little as a single line of dialogue or simply by never mentioning them again. Past explanations for character departure include going to Kenya and moving to Paris to model. You’re telling me you couldn’t send Adam to Europe for a fancy testosterone trial or something?

Overall, the petulant indignation of these writers in response to sincere criticism of snuffing out crucial representation speaks volumes about just how much further the media has to go in terms of its handling of queer subjects. If even the most three-dimensional portrayals can be milked as award bait and then thrown under the bus for any totally non-sequitur issue of the week, it isn’t really all that progressive, is it? Groundbreaking would be showing that queer people have a new chapter worth living for, even if they have to fight for it. Groundbreaking would be showing queer characters happy in relationships without immediately punishing them with supposedly random acts of fate. Groundbreaking would be showing that queer people can and do go on to lead successful, fulfilling lives.

Writers, what you’re doing isn’t groundbreaking. It’s self-serving. You are jumping on a bandwagon and then cutting your own creations loose the second they become inconvenient. You can’t dust your hands off and tell me shit happens. Try again. Push harder. Instead of shocking me with publicity stunts, make me marvel at just how committed you are to actually telling a character’s story authentically . Lastly, don’t you dare fucking tell me to sit down and shut up. You made a big show of initially bringing our community’s “real” stories into the spotlight and now you have the gall to cherry pick our reaction and whine that we should have been grateful for the inevitable shit sandwich all along? We have precious few torchbearers of alternative identity. The capitalization on such fragile issues is sickening and myopically focused on garnering brownie points for the status quo. I can assure you that the impact of these characters transcends the incubator of your tragically narrow mind and maybe that makes you bitter. At the end of the day, in spite of the most idiotic departures you can think of, these characters symbolize an intense hope and tenacity for those who might not have any other allies in their corner.

For all these reasons and more, I will not allow you to quietly bury your queers.